The internet promised to shrink distances and bring all our friends within reach. Yet most of us can’t remember the last real conversation we had. We live surrounded by faces we recognize but barely remember, voices that flicker and fade between notifications. It’s the loneliest kind of network: with endless contact, but vanishing closeness. Somewhere inside the system designed to bring us together, we lost the very thread of friendship.

The Illusion of Connection

I know what Alix Earle had for breakfast: an iced latte and an oat-milk apology for how tired she is. I know what Emma Chamberlain thinks about burnout, and what that one guy on TikTok eats when he’s “romanticizing life.” But I couldn’t tell you what my best friend did this weekend.

That’s normal now. Which is insane.

We scroll through hundreds of strangers every day, people we will probably never meet but somehow know too well. They post, we react, and for a moment it feels like community. Or so we think.

But the people we care about rarely appear in our feeds. Our friends aren’t optimized for trends, and the algorithm quietly forgets them. “Out of sight, out of mind” wasn’t a proverb. It was a product feature. And none of this is really our fault. It’s not laziness or neglect. It’s a societal blind spot. The tools we built to connect us started rewarding the wrong kind of attention, because we taught them to.

Out of Sight, Out of Feed

Every like, swipe, and pause became a small vote for novelty. The algorithm didn’t invent that pattern; it only paid attention.

We still have every way to reach our friends. WhatsApp, iMessage, Instagram, Snapchat, Discord, FaceTime; all waiting for us to start something. But they depend on what’s visible.

If your friend hasn’t posted or texted in a while, it’s as if they’ve been erased. You forget their birthday until someone else’s story reminds you weeks later. You scroll past a photo of a college friend’s wedding, promise yourself you’ll text them, but forget by the next scroll. Your feed would rather show a stranger dancing in Seoul to a Taylor Swift song. It rewards whoever’s loudest, and silence never stood a chance.

Why Social Media Makes Friendship Hard

Even when you remember, it’s hard to know what to do. You could text, call, or FaceTime, but each one feels like showing up at someone’s door unannounced after disappearing for months.

You open the chat, type “hey,” then delete it. You scroll up, see your last conversation from months ago, and close the app. Maybe you’ll send a meme instead. But even that feels forced. The longer the pause, the heavier it feels.

The tools we have are designed for communication, not reconnection. They work when you’re already talking, not when you’re trying to find your way back.

The trouble is that friendship grows through repetition. You see the same person, hear the same stories, notice the small changes in their quiet routines. How their coffee intake has grown but the sugar’s gone. How their laugh has softened. How their texts have fewer emojis but mean the same thing. They remember your old jokes; you finish their sentences. Those small loops are the comfort of closeness. But repetition doesn’t sell, so the system slowly stopped showing us the people who matter most.

No one meant to ignore their friends. We’re wired to notice what’s new and skip what we already understand. That made sense when we lived in the wild, scanning for danger or opportunity. Now it just keeps us scrolling. Every flick of the thumb is a small lottery of surprise, a flash of motion, a headline, a face. The machine just learned from us and fed it back until novelty became our compass.

Neuroscientists call this the dopamine prediction loop. The thrill doesn’t come from the reward itself, but from not knowing what comes next. It’s the same mechanism that keeps gamblers pulling levers and keeps us glued to the feed. Every scroll is a slot machine for attention.

The Opposite of Friendship

The irony is that what keeps us hooked online is the opposite of what keeps us close in life. It’s a brilliant trick of biology: we’re built to crave surprise, but friendship grows in the opposite direction, through the quiet comfort of what repeats.

It’s no wonder our friendships can’t compete. The internet is built to break attention. Notifications, feeds, and infinite scroll are small interruptions designed to pull you back in. Each one breaks your focus just long enough to keep you reaching for the next hit. That’s how it keeps us scrolling instead of connecting.

Repetition feels dull, but it’s where trust lives. Kids want the same bedtime story every night because sameness feels safe. Adults aren’t different but we hide it behind irony and endless feeds. Friendship needs rhythm, the slow reassurance of being seen again and again. The internet’s business model is interruption. The more often it pulls you back, the more valuable you become.

How We Mistook Visibility for Closeness

That’s how the drift began, one interruption at a time. The shift happened quietly, in tiny scrolls. It took us years to notice what had changed, mostly because it never felt broken. We didn’t question it because it felt good. The numbers kept growing, and growth always feels like progress. The more we posted, the more we convinced ourselves that visibility was the same as closeness. It wasn’t. But it was close enough to fool us for a while.

The telephone once promised to make friendship easier. No more missed visits, no more long waits for letters. But it didn’t make connection deeper; it just made interruption easier. We talked more, but knew less.

What the Early Internet Got Right

Every technology eventually teaches us something about human behavior. Social media’s lesson is that attention feels like connection until you try to use it for friendship. That’s when you realize they run on opposite fuels. One depends on novelty. The other depends on familiarity. That is how we ended up here, surrounded by people yet short on presence.

The early internet was small and clumsy, but it felt human in ways the polished feeds never are.

We met people in chatrooms, forums, and odd corners that only existed because a few hundred people cared about the same obscure thing. Music, movies, heartbreak, whatever made us feel less alone. There were no algorithms to please, no followers to count. Just people awake at the same odd hour, trying to be understood.

We built friendships out of pixels and patience. Traded songs. Shared bad poems. Stayed up late in endless group chats that felt like secret clubs. The quiet check-ins said more than words. We used to sit through silences and wait for replies. We cared enough to ask twice. It was slow, but it was real.

The Cost of Scale

That world helped us find our tribes, our confidants, our midnight friends. It made distance feel smaller and connection feel real. It gave friendship a new kind of oxygen. The problem wasn’t connection. It was what we started doing with it once we had it.

Then the quiet rooms turned into crowded stages. The same tools that helped us find each other started teaching us to perform instead. Likes replaced letters. Posts replaced presence. Attention replaced affection. And friendship quietly turned into maintenance. We know more about the world than ever, but somehow we lost our friends.

Every system ends up optimizing for what it can measure. The internet didn’t kill friendship; it just made it harder to keep one alive. Clicks, views, and time spent are easy to count, and to sell. Friendship never fits into that math. It’s built on repetition, patience, and memory, things no dataset can capture.

And that’s where the damage began. Friendship is proof that someone has seen you fail, change, try again, and still wants to stay. It grows through ordinary time, shared jokes, repeated stories, the slow work of being remembered. Without it, we don’t just feel lonely. We lose the mirror that reminds us who we are.

For a while, the internet tried to hold that mirror. It reflected what made us pause, what made us laugh, what kept us there longer. But eventually, it started shaping instead of showing, repetition disguised as novelty. What began as connection quietly became conditioning.

Attention became the new currency. We started competing for it. Competition makes people louder, and louder people get noticed. Before long, the quiet parts of friendship faded from view.

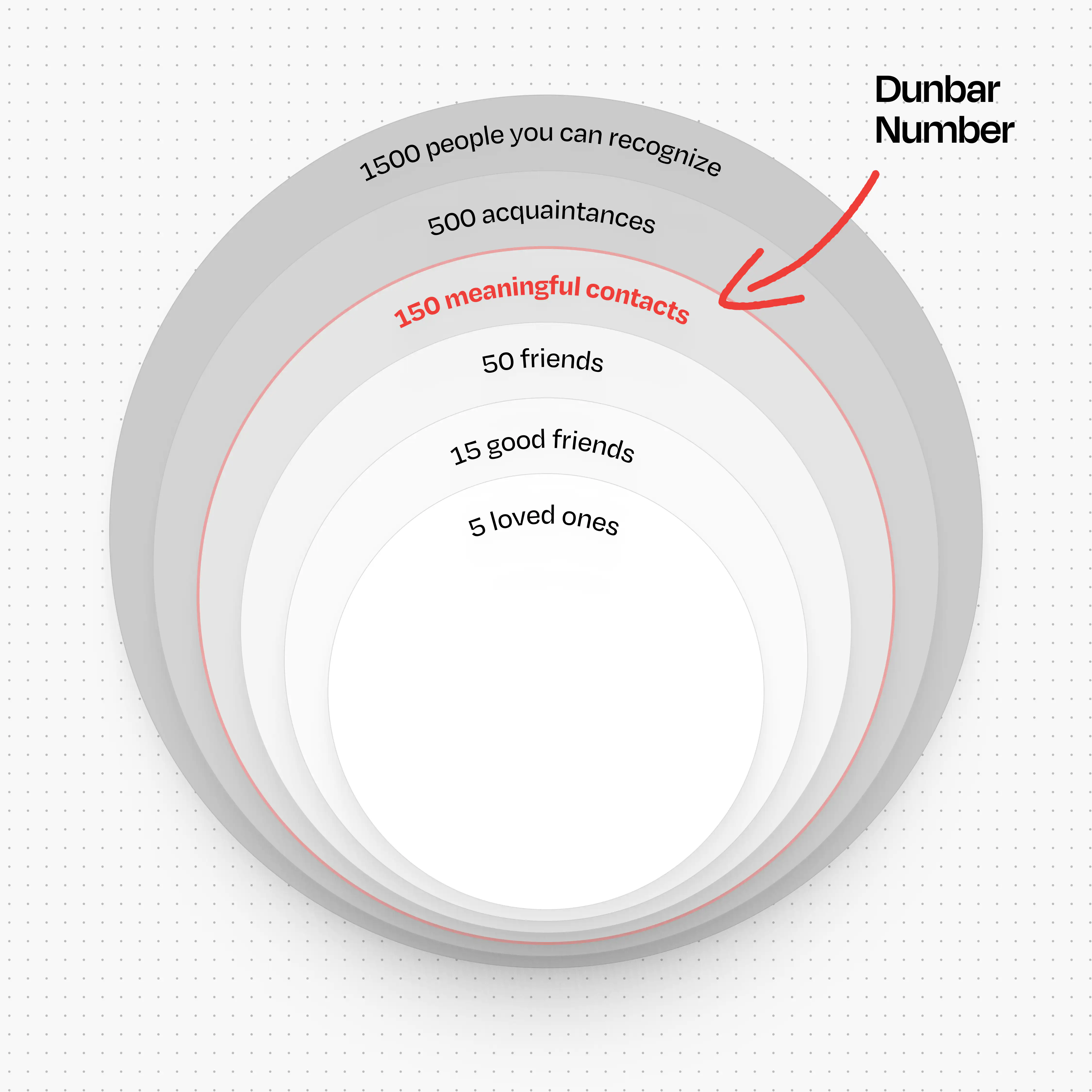

Our minds weren’t built for this kind of scale. Anthropologist Robin Dunbar once said we’re built to hold about 150 real relationships. Social media gave us thousands, and stretched them thin. A village gave us context: who’s hurting, who’s happy, who needs help. A feed gives us exposure without empathy. Now, everyone’s visible but no one’s seen. Ordinary life never stood a chance.

When Progress Forgot Friendship

Over time, we started believing that the only stories worth telling were the ones that performed well. Progress always forgets something worth keeping. This time, it was friendship.

None of this was planned. It’s just what happens when scale meets human nature. We have always been drawn to what’s new, what moves, what glows. The algorithm didn’t invent that instinct; it only magnified it until it felt normal.

And somewhere along the way, the internet managed to keep everyone connected while forgetting our friends.

We can’t rewind to the early internet or the world that made it possible. But we can remember what made it feel good: small circles, real time, honest attention. The next version of the internet doesn’t need to be bigger. It just needs to feel like a place built for friends again.