The Characters We Believed In

In the 1950s, a woman became one of the most trusted figures in American homes. She was kind, patient and wise. The sort of person who wouldn’t judge you for ruining a pie crust. She taught you how to make a perfect cake, consoled you when it didn’t match your expectations, and gently urged you to try again.

People wrote her letters. Shared family secrets. Asked for life advice. Sent thank-you notes. One man even proposed to her.

Her name was Betty Crocker.

And here’s the twist: she never existed.

Betty Crocker was a corporate invention. A name picked by a company executive to respond to the thousands of letters General Mills kept receiving about baking. The handwriting on the replies was carefully practiced to feel maternal.

There was no real Betty to visit. No phone number to call. And that didn’t seem to matter.

People still wrote to her. Still invited her to weddings. Still told her things they hadn’t told their own parents. Because she never changed. Betty was always in character: warm, maternal, and dependable.

In that way, Betty Crocker did what most brands still struggle to do: She never broke character.

A few decades later, a strange new figure walked into American homes and quietly claimed emotional real estate. He had no origin story. No real name. Just a painted smile and an ad slot between cartoons. And that was enough.

By the 1980s, he was more recognizable to American children than Abraham Lincoln. He didn’t talk much. But he smiled. He handed out fries. And somewhere in the back of your mind, even now, joy still looks like a red box.

His name was Ronald McDonald.

We all know that Ronald isn’t real. But neither is Harry Potter. Or Mickey Mouse.

And yet… some part of us, the child who never fully left, still waits for the Hogwarts letter. Still believes, maybe, just maybe… the train will show up someday.

The Disney Rule: Behavior Before Visual Design

In 1937, during the making of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt Disney formalized a team inside his studio: the Character Model Department. Their job wasn’t to design what characters looked like. It was to define how they behaved.

“I think you have to know these fellows definitely before you can draw them,” Disney said.

Animator Frank Thomas later explained: “Until a character becomes a personality, it cannot be believed.”

How Mickey, Donald, and Goofy Became Believable

The work began long before the first sketch. They wrote character sheets, more like emotional blueprints, detailing how someone walked, what made them anxious, and what made them lose their temper. Mickey was cheerful and curious, but never cruel. Donald had a short fuse but a good heart. Goofy stumbled through life with too much kindness and not enough logic. Each character had rules, rhythms, and emotional boundaries.

That was the rule: personality first, drawing later.

Disney once said, “When people laugh at Mickey Mouse, it’s because he’s human.” Mickey wasn’t funny because he looked like a mouse. He was funny because he got scared, got brave, messed up, and tried again. Just like us.

This principle became gospel inside the studio. Throughout the Golden Age of the 1930s to ’60s, animators were taught to begin with character sheets, and not drawings.

Before people can trust how you look, they need to believe who you are. That belief begins with behavior, and that’s the lesson Mickey’s been teaching for nearly a century. Not just brand storytelling, but character architecture: a blueprint for how a brand should behave, not just look.

Why Personality Came First at Disney

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, two of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” would later write in The Illusion of Life: “Personality always came first. Only then could a drawing move. Only then could it mean something.”

People fell in love with Disney characters because of how they acted. How they reacted. The rhythm of their voice, the timing of their smile, the predictability of their chaos.

Because visual design without behavior is just costume. And behavior without consistency is just chaos. And yet, most brands stop there, at costume and chaos, much before they ever become something people can actually know.

Brand consistency isn’t just visual. It’s behavioral, the quiet repetition that makes a belief possible.

Psychologists would later name this as the Mere Exposure Effect: the more often we see something, the more we start to trust and like it. Even if it’s fictional. Even if it’s a clown in red shoes. Or a castle with moving staircases.

What matters is that it behaves the way we expect it to behave. Every single time. And when that happens, something strange occurs. We stop questioning if it’s real. We simply believe.

As psychologist Daniel Kahneman put it: “Familiarity breeds liking.”

Science would eventually explain what characters had always known: reliability earns belief faster than truth.

The Psychology of Branding and Familiarity

The psychology of branding begins with one truth: what feels familiar often feels right, even when it isn’t.

In the 1970s and 1980s, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky uncovered something strange about how we think. They noticed that people often made decisions based not on logic, but on fast, automatic reactions. This became the foundation of what Kahneman would later call two systems of thinking.

System 1 is fast, emotional, and intuitive. System 2 is slow, rational, and effortful. We like to believe our decisions come from System 2. But most of the time, System 1 moves first. System 2 just comes in later to explain the choice.

Kahneman, Damasio, and Emotional Decision-Making

In the 1990s, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio discovered something that added even more weight to Kahneman’s idea. He studied patients with damage to the part of the brain responsible for emotion. They were intelligent and articulate. They could solve logical puzzles, analyze data, weigh pros and cons.

But they couldn’t decide.

Even simple choices like tea or coffee, pen or pencil, left them stuck in endless loops. What they lacked wasn’t logic. It was preference. And preference, Damasio discovered, comes from emotion.

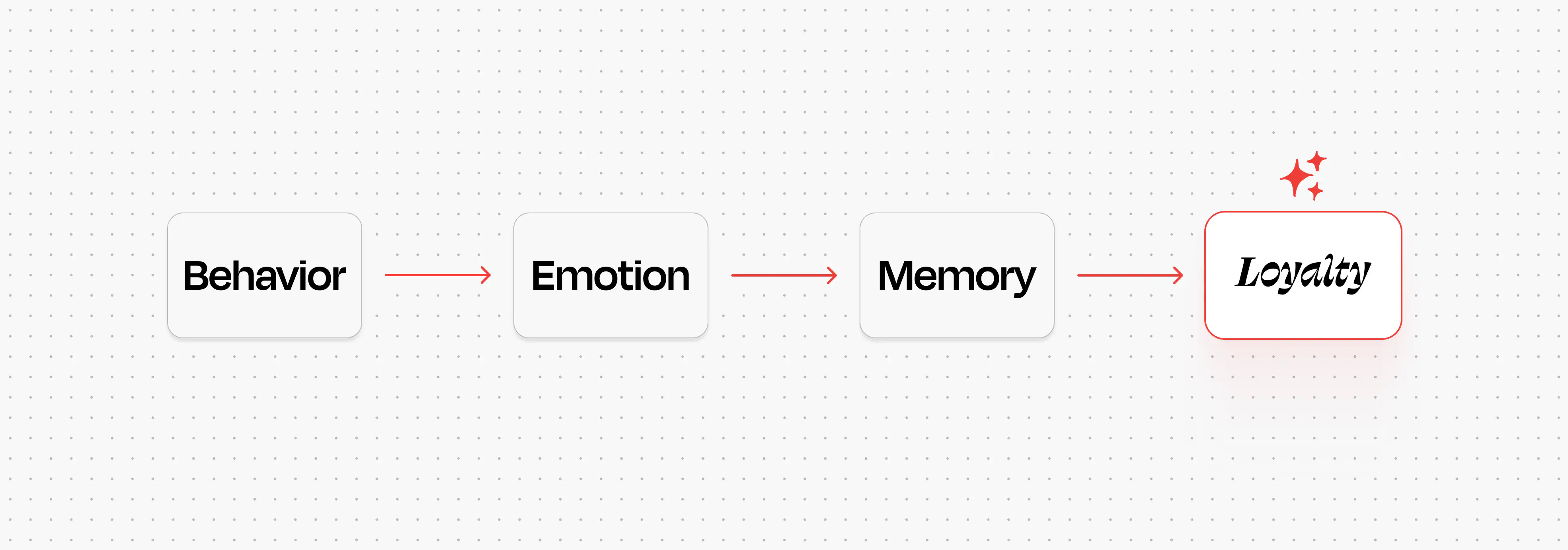

This is the root of emotional branding: people don’t trust facts first. They trust feelings that repeat.

Cognitive Fluency and Emotional Trust

Emotion is how the brain says, “this matters.” It’s how we assign weight to decisions, not through logic, but through ease, rhythm, and repetition. Psychologists call this cognitive fluency: the easier something is to process, the more familiar it feels. And the more familiar it feels, the more we trust it.

Over time, those emotional markers (feelings) become memories. Memories become habits. And habit becomes the story we call loyalty.

Branding doesn’t build recognition. It builds emotional preference. Because long before people can think, they feel.

The Mistake Most Brands Still Make

Most brands today do the opposite. They start with the drawing. The logo, the typography, the colors, the brand assets. They obsess over “look and feel,” as if recognition were the same thing as resonance. They rush to define their brand identity through visuals, before ever asking who they are emotionally.

But the best brands, the ones that last, still follow Disney’s rule. They don’t ask, how do we want to appear? They ask, who are we, and how do we behave in the world?

Because branding, at its core, isn’t about being noticed. It’s about being known. And you don’t get known by what you wear. You get known by how you show up, again and again, in a way that makes people feel like they’ve met you before.

When people say a brand has a personality, they usually mean it uses emojis on Twitter (X) or uses a certain color palette or sounds quirky in emails.

But personality isn’t decoration. It’s not a tone of voice, or a marketing tool. It’s a behavioral contract. The best brands don’t just look familiar. They behave like someone you already know.

When Brands Behave Like People

Netflix, for instance, doesn’t behave like a company. It behaves like Dr. Jason Bull, a character who studies your habits, anticipates your decisions, and curates your experience before you even ask. Not emotional or loud, but cool, predictive, and quietly certain.

Netflix, Apple, Coke, and Duolingo as Characters

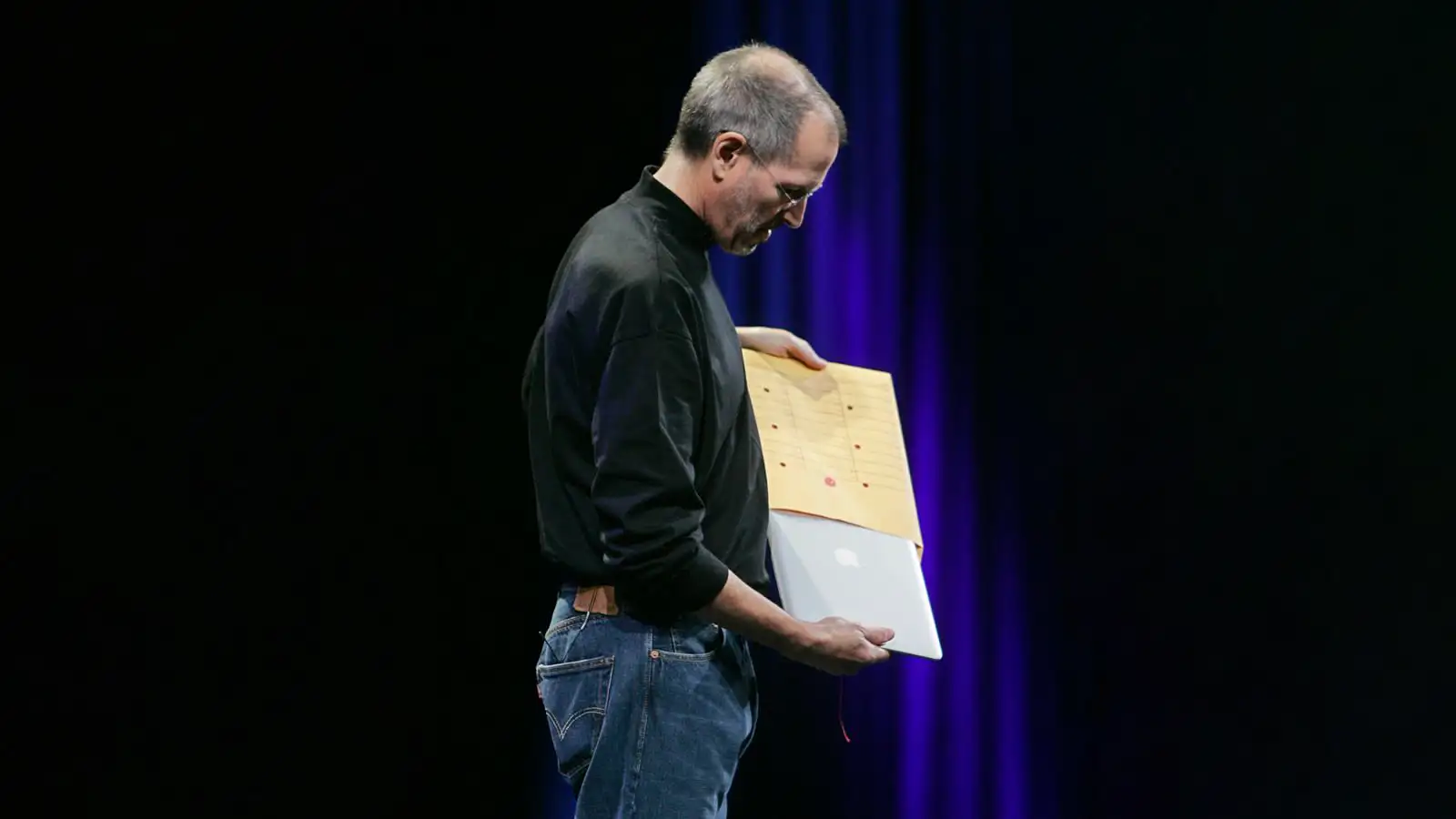

Apple plays a different role. It doesn’t speak unless it has something worth unveiling. It enters like a magician, not a marketer, slow, deliberate, dressed in restraint. Apple behaves like the myth of Steve Jobs, not the man.

One moment captured this better than any ad ever could.

When Jobs unveiled the MacBook Air in 2008, he didn’t talk specs or benchmarks. He simply pulled it out of a manila envelope that he had on stage with him the whole time. A quiet, theatrical gesture, without any shouting or selling, which spoke more about Apple’s character than a hundred product videos.

Then there’s Coca-Cola, Tom Hanks in a red sweater: wholesome, reliable, and universally liked. It has been playing the same role for decades: the taste of childhood, the companion to comfort, the emotional shorthand for “everything’s going to be okay.”

Coca-Cola built an emotional connection with customers long before it started running ads. Its rhythm, not its realism, did the work.

Then there are brands that demand attention.

Duolingo doesn’t nudge you politely. It throws a tantrum. It chases you down with memes and guilt and fluorescent green feathers. It’s not a teacher. It’s a performer, Jim Carrey in The Mask, holding you accountable through chaos. And weirdly, it works.

What makes these brands memorable is their brand behavior, not their features or their claims, but how they act.

Most brands don’t think this way. They try to be everything at once: funny and wise, cool and loud, real and mythical. They bend to trends, switch tones by channel, and dilute their identity in the name of reach.

The best brands weren’t designed. They were cast.

They don’t try to say everything. They try to say one thing clearly, rhythmically, and relentlessly across every screen, surface, and second. And that’s what builds trust. Not through words, but through behavior. Not through campaigns, but through character.

Consistency Is What Makes Us Believe

Ronald always smiles the same way, wears the same clothes, and never changes tone. And to a child, that can feel more human than most of the real people in their life.

Because children understand something we forget as adults: Trust doesn’t come from proof. It comes from familiarity, from a quiet sense of “I know who this is. And I know what to expect.”

Which is why we flinch when a fictional character acts out of sync. We expect them to behave a certain way, and when they don’t, it breaks the spell. Psychologists call this a schema, a mental framework for how someone is supposed to behave.

This is character-based branding in its purest form: Consistency of behavior, not just visuals.

Schema, Association, and the Pattern of Trust

The best brands don’t feel like companies. They feel like characters who always stay in role.

Nike doesn’t just sell shoes. It plays the role of a coach: focused, demanding, unwilling to let you quit. Duolingo is your unhinged accountability buddy. Apple is the obsessive artist who would rather fail than compromise.

None of this is “the truth.” It’s performance, repeated so consistently that it starts to feel like truth. Branding is picking a character and then committing to it.

Because once people recognize the role, they ask a deeper question: “Do I see myself in this?”

That’s what really builds loyalty. Not relatability, but aspiration. Not just a character who behaves the same way, but a character who behaves the way we wish we did. A version of us we like, or need, or quietly aspire to become.

Some brands feel like mentors. Others feel like sidekicks. Some feel like the voice in your head that won’t let you skip leg day.

Duolingo is annoying on purpose. Not because they don’t know better. But because they know that deep down, we want someone to hold us accountable. Someone to care enough to pester. We forgive the noise when it comes wrapped in concern.

Because sometimes, pestering is love. And branding is just love, written in a language people already trust.

Loyalty Doesn’t Come From Logic. It Comes From Feeling.

Psychologists call this association: the emotional shortcut your brain takes when it connects a pattern to a feeling. It works like this:

- We learn how something behaves.

- We decide how we feel about it.

- If the feeling is safe, warm, or rewarding, we keep coming back.

- And eventually, we stop seeing it as a brand.

We start seeing it as a relationship. That emotional pattern is how some brands achieve Mental Market Monopoly.

As Maya Angelou said:

“People will forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel.”

Which explains a lot about branding. And why businesses spend billions trying to make you feel something.

What This Means for Modern Branding

You might understand consciously that Brand A is cheaper, faster, or technically better. But something keeps pulling you back to Brand B. Not because of specs or logic, but because the last time you used it, it left a mark. A flicker of joy. A sense of control. A bit of calm in a noisy world.

People Don’t Buy the Best. They Buy the Familiar.

Most people think branding is a logo, a tagline, a color palette. But those are just signals. What matters is the pattern those signals form over time. The rhythm. The emotional tone. The predictability.

Because humans evolved to trust patterns, not facts.

If the red berry made you sick once, you avoided it. If a symbol meant warmth or warning or home, you remembered the symbol. Your brain didn’t need a scientific explanation. It needed repetition.

We still operate this way. We may not understand what makes one app “cleaner” or “nicer,” or why one shampoo feels better. But we remember how it made us feel. And that memory becomes the shortcut we take next time.

The best branding strategy doesn’t start with a campaign. It starts with a character.

If people stayed loyal to what made the most logical sense, the world would look very different.

Coke would have lost to Pepsi. Mercedes would have collapsed under the weight of cheaper options. And nobody would buy twelve-thousand-dollar watches in a world where every phone tells time.

But that’s not how people work.

We don’t stay loyal to what they understand. We stay loyal to what we feel. That’s not a flaw. That’s the human operating system at play.

In Part 2, we’ll explore how to define and codify a brand’s character, and perhaps, to build behavioral templates like character bibles.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Most Trusted Brands & Character-Based Branding

What is character-based branding?

Character-based branding is the strategy of building a brand around a consistent personality, emotional rhythm, and behavioral identity, much like a fictional character in a story.

How does emotional branding work?

Emotional branding uses behavior and repetition to create feelings, which become memory, and then preference. It isn’t about being loud, but about being believable over time.

How does emotional branding differ from traditional marketing?

Traditional marketing sells features or benefits. Emotional branding builds trust and memory by making people feel something, before they even think about what they’re buying.

Why do we trust brands that feel familiar?

Because the brain rewards repetition. Familiarity feels safe, even when we know something isn’t “real.” That’s why emotional consistency builds belief faster than truth.

Why do brands like Disney or Apple feel emotionally trustworthy?

Because they repeat behaviors that create familiarity and emotional safety. Psychologists call this the Mere Exposure Effect: the more we see something, the more we trust it.

What’s the difference between brand recognition and brand loyalty?

Recognition means you’ve seen it before. Loyalty means you feel something when you see it again. The best brands turn attention into emotion, and emotion into habit.

Can you measure whether a brand is ‘in character’?

You can, but not through logos or taglines. You’ll need behavior-driven benchmarks. That’s what Part 2 will unpack.