Sometimes survival depends not on what we gain, but on what we’re willing to lose. From mountaineers cutting free trapped limbs, to businesses trimming product lines, to designers stripping away excess - there’s a timeless principle at play: subtraction saves. This is the story of “life over limb,” a lesson carved in survival, medicine, and strategy, reminding us that wholeness is not always worth more than continuity.

The Boulder and the Knife

In 2003, mountaineer Aron Ralston set out alone to explore a remote canyon in Utah. What began as an ordinary adventure became one of the most harrowing survival stories of our time.

A boulder slipped, pinning his arm against the canyon wall. For six days he waited, dehydrated, delirious, and watching his trapped hand slowly turn gray. Then came the impossible choice.

Either cut off his own arm with a dull pocketknife or die there in the desert.

Ralston lived because he chose survival over wholeness, life over limb, a survival principle first rooted in medicine and still shaping business and design today.

Years later, Danny Boyle’s Oscar-nominated film 127 Hours retold Ralston’s ordeal for the big screen. But the reason his story first captured global attention had nothing to do with Hollywood. It was because the choice he faced, sacrifice or death, embodied a principle as old as medicine and war:

Life over limb.

What does “Life over Limb” mean?

Life over limb means survival matters more than wholeness. The phrase originated in medicine, where surgeons performed amputations to save lives, but today it’s used in business, design, and strategy when hard cuts ensure survival.

TL;DR for Life Over Limb

- Means survival matters more than wholeness.

- Originated in medicine and battlefield amputations.

- Modern examples: Simone Biles, Venice, Netflix, Apple.

- L.I.F.E. Framework: Limb vs body, Impact, Future cost, Execute.

- Lesson: Subtraction is survival, in bodies, businesses, and nations.

What “Life Over Limb” Really Means

The origins of “life over limb” were anything but poetic. They were visceral, bloody, and born out of necessity.

In the 19th century, before antiseptics and antibiotics, infection turned the smallest wound into a death sentence. The principle of life over limb in medicine meant amputation was often the only survival strategy. Surgeons practiced early forms of triage, deciding who could be saved and who could not.

A crushed leg from a carriage accident or a musket ball tearing through bone could fester within days. Gangrene spread quickly, blackening tissue and poisoning blood. Families gathered at the bedside, surgeons with bone saws in hand, all facing the same cruel equation: keep the limb and lose the life, or sacrifice the limb and buy survival.

The brutality was magnified in war. At Gettysburg in 1863, tents glowed through the night as cannon fire rumbled in the distance. Surgeons worked without pause, their instruments dulled from overuse, their hands raw from washing. Outside, piles of severed arms and legs grew higher with each passing hour. Historians estimate that nearly three-quarters of battlefield surgeries ended in amputation.

By World War I, the principle had hardened into a system: triage. Doctors sorted soldiers into categories: those who would survive without immediate care, those who might survive if treated quickly, and those who were too far gone. It was cold. It was cruel. But it saved the most lives possible. The human body was no longer sacred in its wholeness. It was a system where parts could be cut away so the whole might endure.

From operating theaters to battlefield tents, the rule was the same: hesitation was lethal. Life first. Limb second.

“Hesitation was lethal. Life first. Limb second.”

Modern Examples of Life Over Limb: Simone Biles

On a summer morning in Tokyo, the world’s eyes were fixed on Simone Biles, the most decorated gymnast in history. By the time she walked into the arena at the 2021 Olympics, she had already rewritten her sport with gravity-defying routines that no one else dared attempt.

Broadcasters built entire storylines around her. Advertisers tied campaigns to her name. Young athletes across the globe stayed awake at impossible hours just to watch her bend physics to her will.

And then, she stopped.

Midway through the Games, Biles stunned the world by withdrawing from competition. She spoke of the twisties, a terrifying mental block where the body betrays the brain, flipping and twisting uncontrollably. In gymnastics, the twisties are not just inconvenient. They can be fatal.

“Sometimes the bravest act is stepping back, not pushing through.”

Her choice was brutal: compete and risk catastrophic injury, or step back and preserve her health. This was life over limb applied outside medicine, a survival principle reframed for modern sports. For a culture addicted to winning, her decision felt almost unthinkable. Yet it was an act of radical clarity.

Like a battlefield surgeon forced to amputate, Biles sacrificed medals, records, and the myth of invincibility to protect something far more essential, her life, her health, and her future.

It was life over limb, reframed for the 21st century.

When Cities Amputate Themselves

The same principle plays out far from arenas and bright lights.

In Venice, Italy, the fate of the city is shaped not by wars but by water. Built atop wooden pilings in a shallow lagoon, its palaces and piazzas have long endured the periodic acqua alta, the high tides that flood streets and stairways. For centuries, these were nuisances, not existential threats.

But the nuisance became survival. In 2019, record flooding submerged over 80 percent of the city, inflicting more than €1 billion in damage. The lagoon that once protected Venice now menaced it.

As the waters rose, the population of historic Venice collapsed. In the 1970s, 175,000 people lived in the city center. Today, fewer than 50,000 remain. To leave was to sever a limb of identity, memory, and place. To stay was to risk life itself.

Venice is not alone. Villages in Alaska have voted to relocate inland as permafrost melts and seas creep higher. Entire island nations in the Pacific are preparing to abandon homelands that have anchored their cultures for millennia.

Moving an entire city sounds unthinkable. But moving apartments, leaving a hometown, even shutting down a business, it all feels the same. You’re cutting away identity to protect survival.

How Businesses Apply Life Over Limb: Netflix, Apple, Kodak

In medicine, amputation is an act of last resort. In business, it is often the difference between survival and extinction.

Kodak dominated film for decades. But when its own engineer built the first digital camera in 1975, leaders buried it to protect film. Competitors didn’t. By 2012, Kodak was bankrupt. In trying to save its limb, it sacrificed its life. This refusal to cut was the opposite of corporate amputation, the kind of strategic sacrifice businesses need to survive.

“A profitable limb can still be septic.”

Netflix chose differently than Kodak. In the mid-2000s, when its DVD-by-mail business was booming, Reed Hastings made a call that looked reckless: pivot to streaming. Within a few years, DVDs plummeted. But Netflix survived because it amputated early. In 2013, it doubled down again, pouring millions into original shows like House of Cards and Orange Is the New Black. Critics scoffed at a DVD company making television. Today, Netflix commands an industry it nearly abandoned.

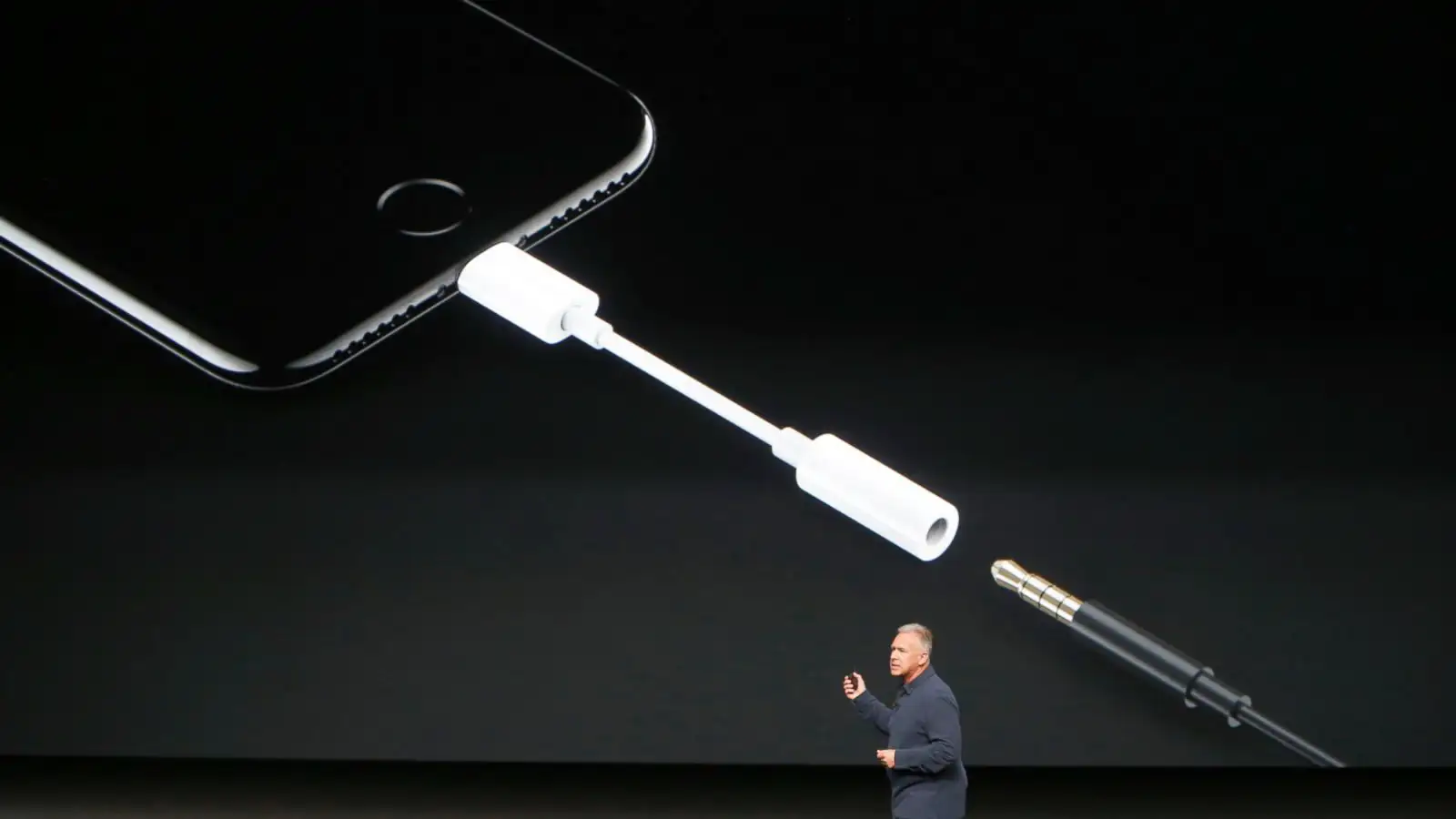

And then there’s Apple, perhaps the boldest practitioner of life over limb in modern business. From the floppy disk to the CD drive to the headphone jack, Apple repeatedly cut what others thought essential. Each decision sparked outrage. Each also paved the way for sleeker design, new ecosystems, and billions in revenue.

The most visible cut came in 2016, when it killed the iPhone’s headphone jack, a port used by billions and seemingly irreplaceable. The backlash was immediate. Competitors mocked Apple’s “courage.” But the gamble worked. AirPods, launched the same year, now generate more revenue than Nintendo, Spotify, or even Adobe. What looked reckless became one of the most successful amputations in corporate history.

Apple’s cuts were not just business decisions. They revealed a deeper principle: subtraction as survival.

Subtraction as a Design Principle

Technology often evolves not by adding more, but by cutting away. To innovate is to amputate, removing what feels essential to make room for what comes next. This kind of innovation by subtraction is design’s version of life over limb.

Instagram launched in 2010 with almost nothing but photo sharing and filters. No web version, no menus, no clutter. The cut made it irresistible, drawing a million users in two months and a $1 billion acquisition by Facebook.

Twitter’s 140-character limit worked the same way. At launch, critics mocked it as too restrictive, too amputated. Yet that very constraint gave rise to the platform’s snappy, viral style of communication. The cut created the culture.

“Subtraction is survival.”

The flip side is equally telling. BlackBerry once commanded more than half of the U.S. smartphone market. But it clung to its physical keyboard, refusing to amputate what customers believed they couldn’t live without. As the world embraced touchscreens, BlackBerry’s grip collapsed. By 2016, its market share had fallen below 0.1 percent.

The broader truth is clear: subtraction is survival. In design, as in medicine, the courage to remove often defines the difference between extinction and endurance.

When Nations Face the Knife

The principle of life over limb does not stop with bodies or businesses. Entire nations have had to make amputations to survive.

After World War II, Britain faced this choice. Its empire stretched across the globe, but its economy was in ruins. Maintaining colonies meant pouring resources into military control while its people endured rationing at home. The limb was imperial pride; the life was national survival. Britain let go of the colonies and began rebuilding. The empire ended, but the country endured.

The United States, too, once faced its own rotten limb. In the Civil War, the Union had to decide whether to tolerate slavery to preserve peace, or to tear it out at catastrophic cost. The war was the amputation. The Union survived because it cut.

Even in victory, choices of amputation shaped policy. After World War I, Europe demanded revenge against Germany, crippling reparations that planted the seeds of another war. After World War II, the United States chose differently. The Marshall Plan amputated vengeance, replacing it with aid. It preserved peace in Europe for generations.

Sometimes the amputation comes not from politics but from physics. In 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed, severing fifteen republics to save itself from civil war and famine. More recently, climate change has forced entire communities to vote with their feet: Alaskan villages relocating inland, Pacific island nations preparing to abandon ancestral homelands. The land itself is the limb. People are the life.

Policy, at its heart, is triage. Leaders must decide what parts of a nation can be saved, what must be cut, and what sacrifices will keep the body alive. Hesitation carries its own cost. The world remembers scars, but it buries hesitation. These are life over limb choices in policy and survival strategy.

The Life Over Limb Framework: How to Decide What to Cut

This framework translates the survival rule of life over limb meaning into a tool for business strategy, design, and policymaking.

1. Identify the Body vs. the Limb

- The body is what must endure: life, people, mission, survival.

- The limb is valuable but expendable: a product line, a tradition, a symbol, an attachment. If I lose this, can I still exist and regrow?

2. Diagnose the Threat

- Ask whether keeping the limb risks killing the whole.

- In medicine, this was gangrene. In business, it’s legacy models. In policy, it’s unsustainable pride. Am I protecting the limb at the cost of the body?

3. Calculate the Cost of Amputation

- Every cut carries pain: lost revenue, angry customers, grieving citizens.

- But delay often carries a greater cost: decay spreading to the core. Which scar can we live with? Which wound is fatal?

4. Execute Decisively

- Hesitation kills. A surgeon who waits too long loses both limb and life.

- Companies that half-cut bleed out slowly. Nations that hesitate are consumed by unrest. Am I dragging out decay, or making the clean cut?

5. Adapt and Regrow

- Scars become part of identity. Survivors adapt. Companies reinvent. Nations rebuild.

- The absence becomes space for something new: AirPods after the headphone jack, peace after revenge, life after Ralston’s canyon. What future becomes possible only after this cut?

Mnemonic: L.I.F.E.

- Limb vs. body → distinguish what is expendable from what is essential.

- Impact of threat → understand the real danger of keeping the limb.

- Future cost → weigh scars against extinction.

- Execute & evolve → cut decisively, adapt, regrow.

Who Needs This Framework Most?

The principle of life over limb is universal, but it echoes differently depending on where you stand.

For Individuals

We carry our own limbs: jobs that drain us, habits that destroy us, relationships that suffocate us. Letting them go feels like losing part of ourselves. But the real loss is staying attached when they’re already killing us.

The cut that hurts now saves your future self.

For Founders

Early products, first customers, even brand identities can feel sacred. But a company is not its first limb. The body is the mission and momentum. If a limb turns toxic, amputate it before it poisons the whole.

Don’t confuse your first product with your real company.

For CXOs

Legacy is seductive because it looks healthy on the balance sheet. Kodak’s film, Nokia’s buttons, Blockbuster’s late fees all made money until they didn’t. Leaders must spot rot before the market does.

A profitable limb can still be septic.

For Strategists

Strategy is triage. Resources can’t save everything. Trying to keep every project alive starves the body.

If you don’t cut, the market will.

For Designers & Creators

Great products are defined by what they cut: Twitter’s 140 characters, Instagram’s feed, Apple’s missing ports.

Subtraction is identity.

For Policymakers

Nations, like bodies, can rot from pride. Land, symbols, or traditions may be precious, but people are the life. Survival demands choosing humanity over heritage, adaptability over nostalgia.

The scar of loss is better than the silence of extinction.

At every level, personal, corporate, political, the question is the same:

Am I protecting something essential, or just defending a limb that’s already killing me?

The Scar That Saves

What makes life over limb endure is not just its history but its relevance to every future we face. Climate upheaval, technological disruption, shifting identities, all will force us to decide again and again what can be spared and what cannot.

Survival is never neat. It asks us to carry scars, to live with absences, to adapt to bodies, businesses, and nations that will never look the same again. But scars are not failures. They are proof that something was saved.

Aron Ralston’s scar is still visible. He lost his arm, but not his life. Apple’s missing headphone jack left a scar that became an ecosystem. Nations scarred by Partition or collapse still live, still adapt, still rebuild.

A scar is proof that something was saved.

Life first. Limb second.

Frequently Asked Questions About Life Over Limb: Meaning, Origins, and Lessons for Today

What does “life over limb” mean?

It means choosing survival over completeness, even if it requires painful sacrifice.

Where did the phrase “life over limb” come from?

The idiom originated in medicine, where surgeons amputated infected limbs to save patients’ lives.

How can businesses use the life over limb principle?

By cutting failing products, outdated traditions, or harmful practices early to preserve the company’s mission.

What is the Life Over Limb framework?

A structured way to decide when to cut what feels essential to protect survival using L.I.F.E.: Limb vs body, Impact, Future cost, Execute.