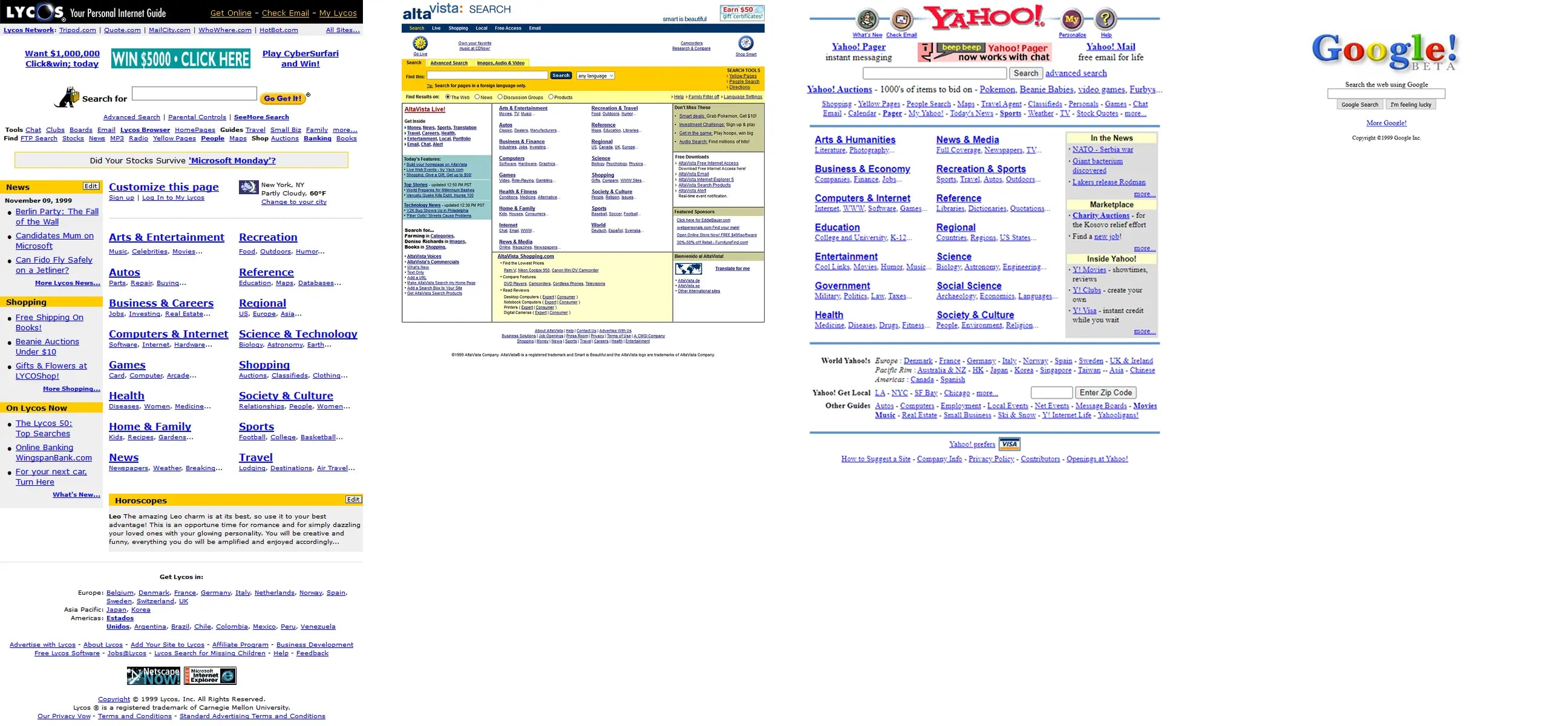

When Google first launched in the late 1990s, people didn’t trust it.

The problem? It looked too simple.

At the time, search engines like Yahoo, AltaVista, and Lycos were packed with news, stock prices, weather updates, and ads. A search engine was supposed to feel busy—like it was working hard to find you information.

Google’s homepage was almost blank. Just a search bar and a button. Users thought the page hadn’t fully loaded. Some even emailed Google, asking if something was wrong.

Investors, too, had their doubts. Where were the banners? The clutter? The flashing stock tickers? Google didn’t just lack a business model; it lacked the chaos that felt like one.

Google had built something better, but it felt wrong because it didn’t resemble the familiar search engines people were used to. It took years for minimalism in search to feel normal.

It’s easy to laugh at those early skeptics now, but it does make you wonder: how many investors walked away from Google simply because it didn’t match their idea of what a billion-dollar company should look like?

We like to think we embrace progress. But when something looks too different, we assume it’s broken. That same pattern repeats everywhere. Every time a new social media app launches, people call it ‘too confusing’, until they don’t.

It’s the same reason someone once asked, “Why do we need this? We already have MySpace and Friendster.” A reasonable question back then, though you don’t hear them bragging about it now.

This resistance isn’t just about technology; it shows up in the smallest details of life.

Ever been forced to create a password with 12 characters, a special symbol, and a number, only to forget it the next day? Or waited at a red light at 2 AM with not a single car in sight, wondering if the universe is playing a joke on you? Or buttoned up a suit on a 100-degree day because, for some reason, this is what “professional” looks like?

We all have such moments, tiny absurdities baked into everyday life. But how often do we stop to ask: Why are we still doing things this way?

It's similar to filling out a paper form at the doctor’s office, while AI writes essays, paints pictures, and drives cars.

It’s not a lack of innovation that holds us back. New ideas are everywhere.

Keyboards that type faster. Diets that actually work. Calendars that don’t feel like quicksand. Despite the apparent benefits, most people stick with the old way. Not because they’re lazy. Not because they don’t care. But because change, even when it’s good for us, feels harder than it should.

That’s Cognitive Gravity, the invisible force of old habits, outdated norms, and inconvenient traditions. It’s not that we don’t want to change. It’s just that staying put feels easier.

Because the old way isn’t just familiar, it feels natural. That’s why people still wear wool suits in humid summer meetings when breathable fabrics could be just as professional. Why we shake hands even after a global pandemic reminded us how easily germs spread. Why do offices still cram workers into open floor plans, despite studies showing they make people less productive? Familiarity doesn’t just comfort us, it shapes our decisions in ways we barely notice.

The Weight of the Past

If you were designing a vehicle from scratch today, would you instinctively give it a steering wheel?

Cognitive Gravity isn’t just about habits. It’s about the weight of tradition and familiarity shaping our defaults.

Take Waymo, for example. Their self-driving taxis in San Francisco no longer need human input, yet the cars still have steering wheels that turn on their own, an eerie, ghostly motion that serves no functional purpose. Engineers could have removed them entirely, but would that make passengers feel more at ease or less? When the interface disappears completely, does trust follow?

Now picture a car with bike-style handles. It would feel wrong, even if it worked just as well. And when fully autonomous vehicles arrive, they won’t need steering wheels at all. But how long will it take before we accept a car with no visible controls? Will we still demand a dashboard, a button to “start” the engine, even when the engine no longer needs starting?

History shows that the way cities are designed locks people into certain behaviors, even long after the original intent is gone.

New York City, with its dense, walkable neighborhoods and extensive subway system, grew before cars dominated urban planning. San Jose, in contrast, was designed around highways and parking lots, making it nearly impossible to function without a car. NYC’s streets were built for people. San Jose’s streets were built for vehicles.

In one, you can step out of your apartment and grab coffee on foot. In the other, getting coffee means a ten-minute drive and circling for parking. The way these cities were planned decades ago still dictates how people live today. And even though urban planners know the benefits of walkable cities, reversing this infrastructure takes enormous effort because Cognitive Gravity isn’t just in our minds, it’s cemented into the roads we drive on.

What happens when autonomous vehicles don’t need traffic lanes the way human drivers do? What happens when cars no longer need streets lined with parking spaces, stoplights, or gas stations? Do we start tearing down parking garages, rethinking intersections, and redesigning entire cities? Or will we keep designing cities for a version of driving that no longer exists?

We don’t just hold on to old roads; we hold on to old ideas. And the same inertia that cements highways and parking lots into cities locks outdated systems into education, careers, and technology.

Schools teach what businesses use, and businesses use what schools teach. It’s a loop that keeps industries locked in place.

Universities don’t train students for the future. They train them for the present (the current job market), just in time for it to become the past.

Businesses then hire based on those degrees, reinforcing the same outdated skill sets. Coding bootcamps and alternative education models are trying to break this cycle. However, they face an uphill battle because the diploma, the credential of the past, still carries more weight than demonstrable skill. This is why we continue to produce more MBAs, while AI may soon require more philosophers, ethicists, and creative thinkers. The world is evolving. Our thinking isn’t.

History is Full of These Moments

Before the 1800s, doctors didn’t wash their hands between surgeries. Germs hadn’t yet been discovered, and cleanliness wasn’t a priority.

In 1846, a Hungarian physician named Ignaz Semmelweis noticed something disturbing: mothers giving birth in hospitals had much higher death rates than those giving birth at home.

He made a simple suggestion: doctors should wash their hands with an antiseptic before touching patients.

His suggestion wasn’t just ignored; it was condemned.

Doctors refused to believe that their unwashed hands were the problem. Many were insulted at the mere suggestion that they could be spreading disease.

Semmelweis was fired, ridiculed, and eventually institutionalized. Decades later, Louis Pasteur’s germ theory proved he was right, but by then, Semmelweis was dead.

People don’t resist change because it’s wrong. They resist it because it challenges what they’ve always known.

Electricity was once controversial. Early skeptics called it too dangerous for homes, and for years, people clung to gas lamps. Alternating current took decades to win over direct current, despite being objectively better.

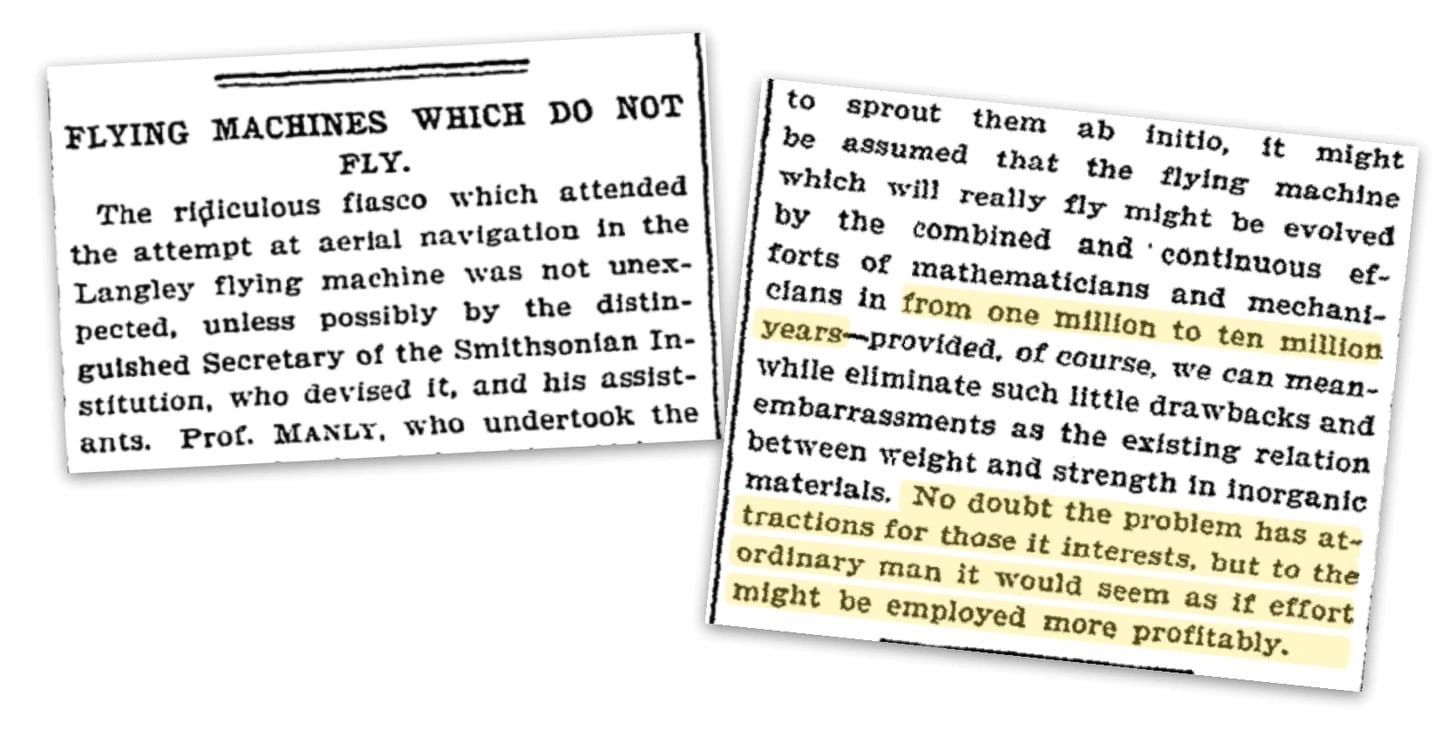

The same thing happened with airplanes. Before the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903, The New York Times predicted human flight might take “one to ten million years” to achieve—only for the Wrights to succeed just nine days later. When the first commercial flight launched in 1914, most newspapers dismissed it as a publicity stunt rather than the start of a new industry. Even investors doubted that air travel could ever compete with trains or ships.

It took decades before flying felt normal. While the Wright brothers proved flight was possible in 1903, and the first scheduled passenger flight happened in 1914, it wasn’t until 1927-1934 that major airlines like Lufthansa (1927), Pan Am (1927), American Airlines (1930), and United Airlines (1934) began regular passenger service.

It took nearly 30 years from the invention of the airplane to the moment air travel became an industry, and even then, it would be decades more before flying felt routine.

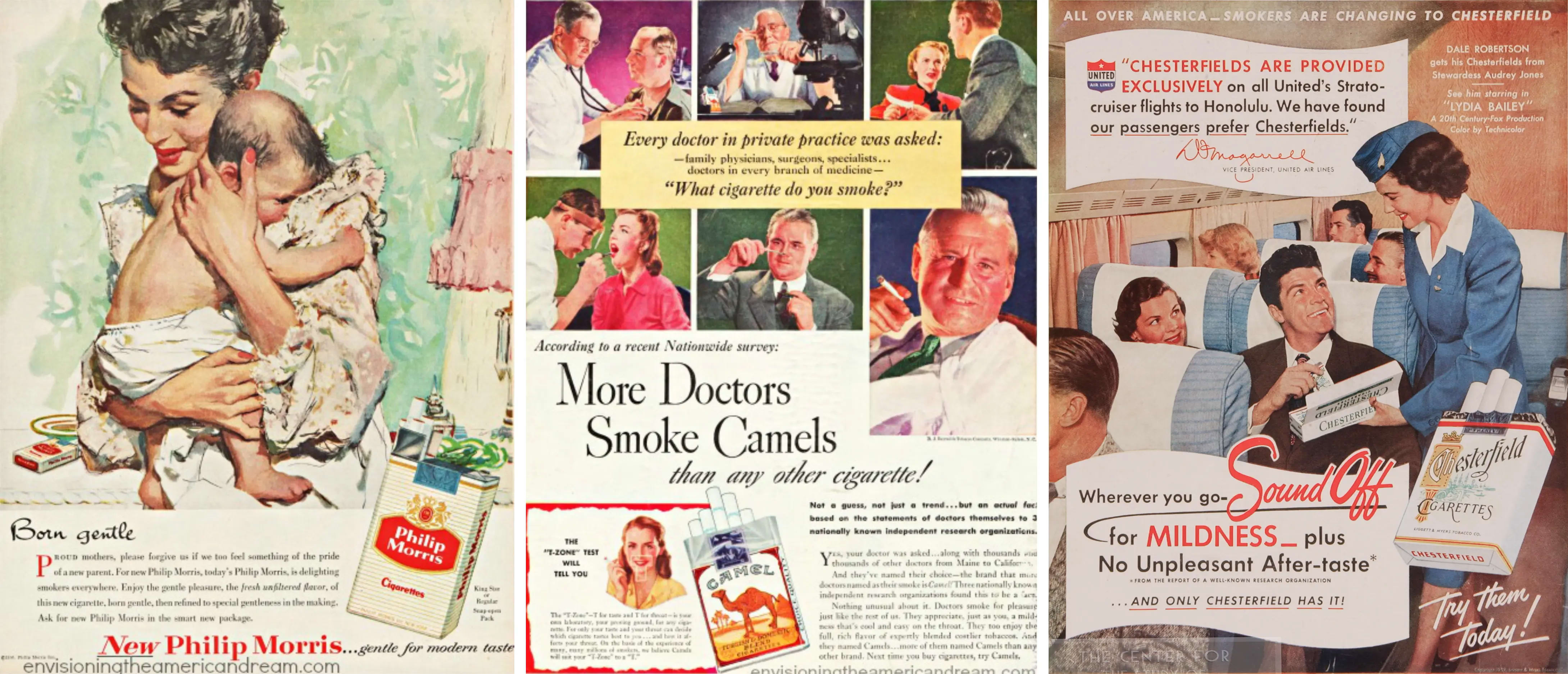

Smoking on airplanes followed a similar arc.

For most of the 20th century, smoking wasn’t just allowed on flights; it was encouraged. Airlines handed out complimentary cigarette packs, and smoking sections were as regular as overhead compartments. Doctors even endorsed cigarette brands in ads, claiming they soothed the throat.

Today, the idea of lighting a cigarette on a plane feels absurd. Not only is it banned worldwide, but the same profession that once promoted smoking now warns against it at every turn. Governments regulate it, doctors discourage it, and society views it as a health hazard rather than a status symbol.

What else do we do today that will seem just as ridiculous in the future?

Will we look back at our open office plans, endless emails, or car-dependent cities with the same disbelief? Will people one day be shocked that we used to sit in traffic for hours? That we worked eight-hour shifts instead of optimizing around energy levels? Why did we cling to fossil fuels long after cleaner alternatives existed? Will AI products always be chat-based, or will they introduce new paradigms that feel more intuitive?

Credit cards struggled for adoption. Consumers didn’t trust them. Merchants feared fraud. And when cars arrived, cities weren’t ready. Roads weren’t paved, gas stations didn’t exist, and the idea of traffic laws was laughable. Infrastructure had to be built before mass adoption could happen.

History doesn’t just show us how much we’ve changed, it reminds us that change always feels wrong before it feels obvious.

And what feels normal today may one day look ridiculous.

Why the Future Looks Familiar

In the 1900s, productivity was associated with documents, spreadsheets, and slides. Today, our work has expanded far beyond those categories, yet modern productivity tools still cling to them.

Notion rethinks documents, but it’s still a document. Slack improves communication, but it hasn’t replaced email; it’s still, at its core, a professional take on WhatsApp. New technologies don’t start with reinvention; they start by mirroring what came before.

We see this same pattern everywhere, even in the way we type.

A century ago, the Dvorak keyboard was designed to replace QWERTY. It made typing faster and reduced finger strain. But by then, millions had already learned QWERTY, businesses had standardized it, and schools were teaching it. The better option never stood a chance because instead of working with Cognitive Gravity, it tried to fight it.

The iPhone didn’t replace flip phones overnight, it positioned itself as a mobile computer, a new necessity rather than just a better phone. Tesla didn’t replace gas cars, it made EVs desirable before they were practical. Netflix didn’t replace TV—it turned content into something you control. Spotify didn’t replace CDs, it made music infinite and on demand.

The strongest ideas don’t just argue why they’re better. They create a new mental category, then become the default.

Why do we stick to old ways? Because we don’t just resist change, we overlook the need for it. We assume the way things are is the way they’ve always been.

That’s Default Reality at work. It’s the invisible force that keeps us from questioning the obvious.

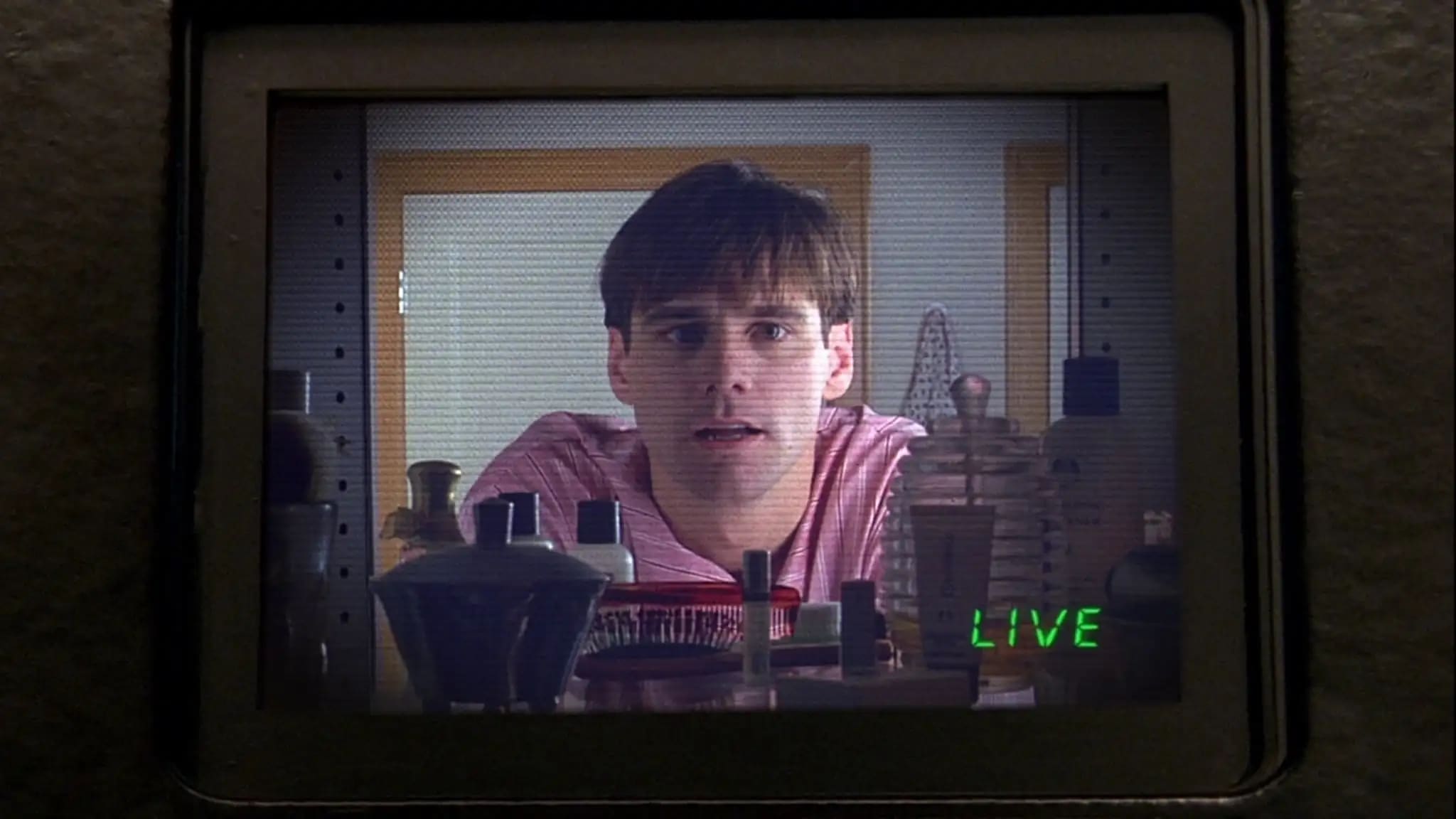

Like Truman Burbank in The Truman Show, most people don’t realize they’re inside a constructed reality until something forces them to see beyond it. Or as Morpheus tells Neo in The Matrix: ‘Most people aren’t ready to be unplugged.’

This inertia isn’t just psychological, it scales. The old way embeds itself into our infrastructure, our institutions, and our habits. Large-scale adoption makes switching difficult. Psychological discomfort discourages experimentation. Evolutionary instincts make outdated behaviors feel natural. The result? We resist not because the new thing doesn’t work, but because it doesn’t feel right.

And the bigger a system gets, the more its past decisions become its future constraints.

The Inertia of Our Systems

Default Reality isn’t just a bias. It’s the foundation of Cognitive Gravity.

It’s why classrooms still resemble factories, despite research showing that lectures aren’t the most effective way we learn. It’s why religions shape laws, family structures, and entire civilizations. It’s why email, invented in the 1970s, still dominates office communication, despite numerous more effective alternatives. Once a system embeds itself into how we think and act, moving away from it feels unnatural, even when it’s clearly outdated.

This isn’t just about personal habits. It’s about entire industries clinging to what’s familiar.

Kodak knew digital cameras were the future. One of their own engineers, Steve Sasson, invented the prototype in 1975. But the company buried it, the film was still profitable, and change felt risky.

By the time Kodak finally embraced digital photography, it was too late. The thing they buried was the thing that buried them.

But the fear of change isn’t limited to businesses. Entire cultures cling to traditions long after their original purpose fades. Religious and social norms shape behaviors, dictating everything from diet to social roles. Once something is widely adopted, it tends to stick.

And it doesn’t stop there. The larger a system grows, the harder it becomes to change. Cities were built for cars, not people. Energy grids were designed for fossil fuels, not renewables. Entire industries depend on the infrastructure they grew out of, making transformation painfully slow. Then there’s habit: once something feels natural, undoing it takes effort. The way people scroll on their phones, organize their mornings, or even hold a pen, Cognitive Gravity locks all in.

Some forces are psychological, others societal, but together, they pull us toward the familiar.

Familiarity keeps us tied to outdated systems. Large-scale adoption makes switching difficult. Psychological discomfort discourages experimentation. And evolutionary instincts make outdated behaviors feel natural.

That’s why people resist new things, not because they don’t work, but because they don’t feel right.

At the core of all this isn’t logic. It’s the pull of the familiar, even when the familiar stops making sense.