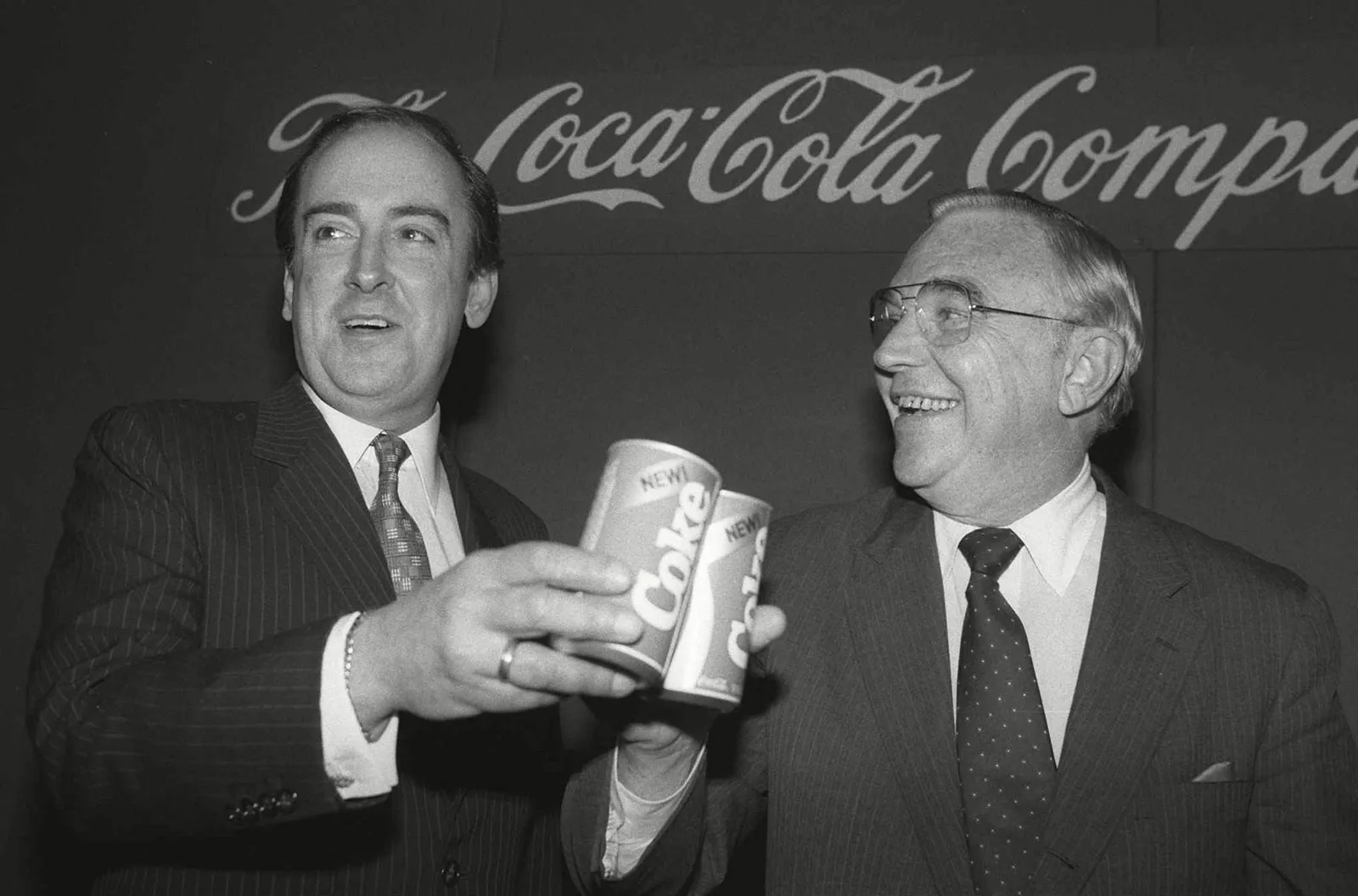

In April 1985, Coca-Cola made what seemed like the most foolproof, data-backed marketing decision of its time.

After 200,000 blind taste tests, years of research, and millions of dollars in development, the results were clear: people preferred the new formula. In surveys and focus groups, participants overwhelmingly chose the sweeter taste of New Coke over the original, and Pepsi. Executives, convinced by the data, pulled the plug on their 99-year-old classic and introduced New Coke.

It lasted 79 days before they had to beg for forgiveness.

“The simple fact is that all the time and money and skill poured into consumer research on the new Coca-Cola could not measure or reveal the depth and abiding emotional attachment to the original Coca-Cola.” — Donald Keough, Coca-Cola President

They had every data point in their favor, but they didn’t account for what Coke really meant to people.

When the backlash hit, Coca-Cola’s phone lines were jammed. Letters poured in by the thousands. People hoarded the last cans of the original formula. One furious caller summed up the failure in a way no market research report ever could:

“You have taken away my childhood. You have taken away my memories.”

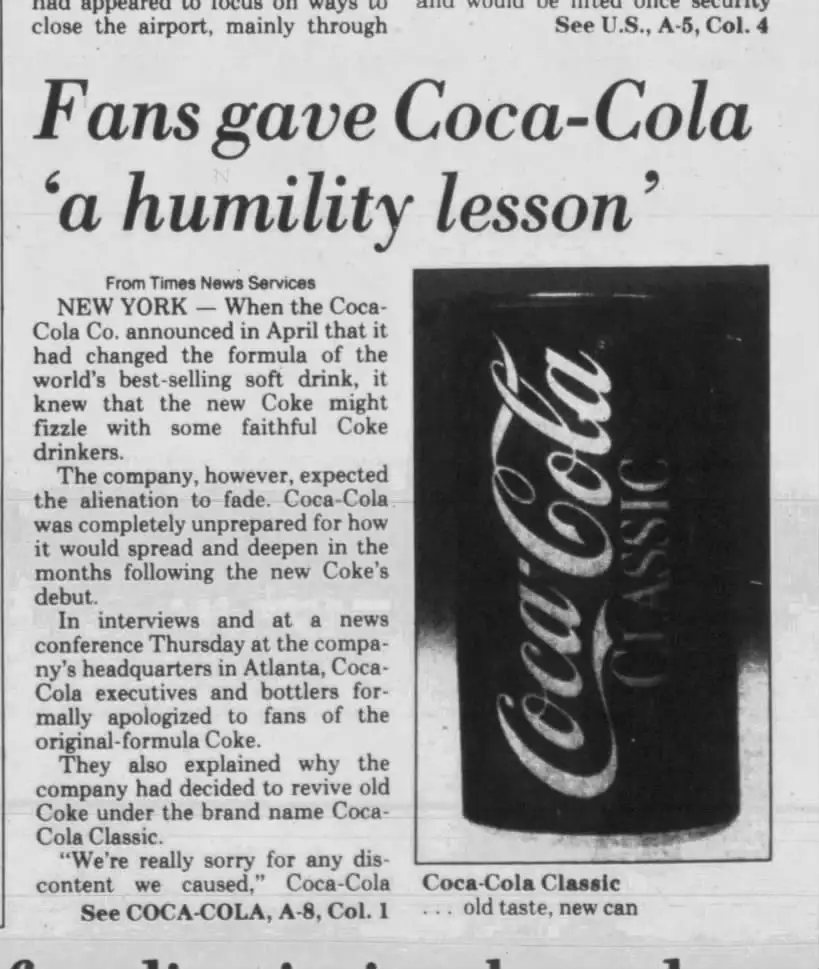

The outcry was so intense that Coca-Cola had to reverse course, reintroducing the original formula as Coca-Cola Classic. The irony? Most hadn’t even tasted the New Coke. They weren’t rejecting the formula. They were rejecting change.

Coke wasn’t just a drink. It was a piece of their identity.

That’s when you know a brand has reached its final form, not just competing, nor winning, but becoming something whose absence feels wrong.

You don’t just buy that brand. You belong to it. In stories, in rituals, in memories.

When Brands Become Beliefs

When people don’t just remember your product, but feel like it remembers them, that’s not just marketing. That’s something deeper.

Coca-Cola had what I call a Mental Market Monopoly: an unshakable place inside people’s minds.

It’s not just a phrase. It’s a mental model. A way to understand how the strongest brands don’t just win markets. They win memory. They don’t just sell, they stick, long after the ad fades, and long after the decision stops feeling like one.

In much of the world, Coke isn’t just a brand, it’s shorthand for soda itself, whether it’s Coca-Cola, Pepsi, or even Thums Up. Some brands don’t just dominate their category. They become the category.

They don’t win on product alone. They win by owning a piece of how people think.

They win on perception.

Because the most powerful brands don’t wait to be chosen, they arrive.

The minute a thought enters your mind, hunger, headache, holiday, or payment, the brand name surfaces on its own. Not as a decision. But as a reflex. As deep as habit. As nostalgic as memory.

This is why you instinctively reach for Tylenol instead of generic acetaminophen. Why Uber means ride-sharing, no matter how many competitors exist. And why no amount of marketing could ever make Colgate frozen dinners sound appetizing.

Because Colgate actually tried.

In 1982, they launched a line of ready-to-eat meals. The product wasn’t the problem. The packaging wasn’t awful. But customers recoiled, because they couldn’t connect lasagna with toothpaste.

The brand that lived in your bathroom had no business showing up in your freezer.

Colgate had spent decades building a mental monopoly in the field of dental hygiene. So when they tried to stretch into food, they hit a wall, one made entirely of perception.

They didn’t lose because the lasagna was bad.

They lost because it said Colgate on the box.

That’s the invisible force at work: once you’ve occupied a space in someone’s mind, it’s nearly impossible to move into another. Not with money. Not with logic.

Because logic doesn’t drive instinct.

“The problem with logic is it kills off magic.”

Marketing isn’t always about reason. It’s about resonance. Because emotional resonance beats logical messaging, especially when perception already owns the room. The mind doesn’t run on spreadsheets. It runs on symbols, memories, and meaning.

Most monopolies are easy to spot: Google in search, Amazon in e-commerce, Microsoft in operating systems. But the most powerful monopolies aren’t just the ones regulators worry about. They’re the ones living quietly in your head.

A traditional monopoly dominates by controlling supply.

A Mental Market Monopoly dominates by controlling perception.

And once perception is entrenched, it’s nearly impossible to displace. Consumers don’t rationally evaluate every option; they default to what feels familiar and reliable.

They become the reflexive choice, the brand you think of before you even know you’re thinking.

Once a brand owns your instincts, there’s no competition. Just confirmation.

That’s a Mental Market Monopoly, when a brand becomes so deeply ingrained in our minds that choosing anything else barely feels like a choice at all.

The Illusion of Choice

People like to think they weigh their options, compare choices, and make rational decisions. But most of the time, they don’t. They just do what feels obvious.

- You don’t make a video call. You FaceTime.

- You don’t search for something. You Google it.

- You don’t look for a sticky note. You grab a Post-it.

- You don’t ask for cola. You ask for a Coke, even if it’s a Pepsi.

- You don’t pay through mobile wallets. You Paytm, even if it’s PhonePe.

- You don’t buy a vacuum flask. You buy a Thermos, even if it’s Milton.

- You don’t say hook-and-loop fastener. You say Velcro.

- You don’t say personal watercraft. You say Jet Ski.

- You don’t say inline skates. You say Rollerblades.

- You don’t make a photocopy. You Xerox it.

At some point, a brand stops being a choice and becomes the default.

Companies don’t just compete for market share. They compete for mindshare. Coca-Cola isn’t just selling soda. It’s selling an idea of happiness and nostalgia. Tylenol isn’t just pain relief. It’s reassurance. These brands embed themselves so deeply into daily life that alternatives don’t just feel unnecessary; they barely feel like options.

This isn’t just about product design, innovation, or go-to-market strategy.

Those get you seen. Mental permanence gets you chosen, again and again.

Breaking into an entrenched market isn’t just about having a better product. It’s about overcoming habit. The hardest part of advertising isn’t getting noticed, it’s changing what people reach for without thinking. That’s why “first to mind” beats “first to market.” Once a brand owns a space in your head, it doesn’t just win, it becomes the only name that comes to mind.

The human brain is a cognitive miser. It takes shortcuts whenever possible. Familiarity is one of the strongest. If a brand stays in your head long enough, it stops being a decision and starts being instinct.

That’s why people don’t ask for “acetaminophen". They ask for Tylenol.

And once a habit is set, breaking it feels harder than sticking with it, even when something better is right in front of them.

Brands dream of recognition.

The best ones become reflexes.

Because this isn’t just product-market fit.

It’s mind-market fit.

From Decision to Default

Most people don’t remember the moment a brand became their default.

They remember that, at some point, the decision stopped feeling like a decision. The brain had quietly filed it under “not worth debating.” Psychologists call it cognitive offloading, when your mind hands a choice over to habit because it trusts the pattern.

That’s the shift: when a brand stops being one of many options and becomes the obvious one.

Zomato didn’t just follow that pattern. It set the standard others would chase.

Yes, others tried to solve the same problem. Some even started earlier.

But solving a problem isn’t the same as becoming the answer.

In 2008, Zomato didn’t offer delivery. It didn’t promise speed. It didn’t chase trends.

It did something more powerful: it became the go-to place for people to decide where to eat.

Before that, restaurant discovery in India was primarily based on word-of-mouth and blind guesses. You asked friends. You hoped for the best. Zomato changed that by scanning menus, organizing them, and putting them online. No fluff, no gimmicks. Just answers.

And slowly, it stopped being a website. It became routine.

You didn’t compare. You didn’t think. You opened Zomato because it was apparent.

So when food delivery became the new battleground, Zomato didn’t need to catch up. It just needed to keep going.

Swiggy entered with a different question. If Zomato answered, “Where should we go out to eat?” —Swiggy asked, “Why go out at all?”

It wasn’t trying to compete on discovery. It reframed the decision entirely. It looked at traffic, weather, laziness, late nights, long meetings, and asked a new question: Should we order in?

That shift changed the category. Swiggy didn’t fight for Zomato’s territory. It invented adjacent territory and built a following around it.

And once a behavior becomes second nature, the brand behind it becomes invisible. You don't think about it. You just tap.

Zomato could have ignored it. But they didn’t. They realized Swiggy had created a new mental category. And if they didn’t start answering that question too, they’d lose the one thing that mattered: mindshare.

So Zomato shifted. From answering, “Where should we go out to eat?” to also answering, “What should we eat from home?”

Same appetite. Different question.

And just like that, one mental market map absorbed another.

Now, Zomato is more than a brand. It’s a reflex. Where to eat. What to order. How to save. What to feel good about after. Zomato answers all of it, without asking for permission.

That’s what happens when a brand stops being a choice and starts being a habit.

Zomato didn’t just expand its business. It expanded its space in your head, one small question at a time, until it became the only answer that mattered.

It didn’t try to win the market.

It made you forget there were other ways to play the game.

The Adjacency Advantage

Zomato’s original question was always social.

Not just "What should I eat?" but "Where should we go out to eat?"

It was a group conversation. A weekend plan. A moment shared.

And now, with District, it’s answering the next social question: "What should we do tonight?"

Maybe that means dinner. Maybe it means a movie, a concert, or a cricket match.

Maybe all of the above.

District didn’t invent a new behavior. It raised the following question on how we plan our social time. It took the same mental space Zomato started with, going out, making plans, and stretched it wider.

Dinner and a movie? Done.

The night you planned? Already won.

Every generation finds its own way to outsource decisions. Our parents asked the waiter. We ask the algorithm.

While others sell tickets, bookings, or food, Zomato is quietly building a planner for urban life.

And it’s not just building. It’s absorbing.

In 2020, Zomato acquired Uber Eats India. It didn’t just buy delivery logistics. It bought a default status. It removed the second guess. It turned food ordering from a decision into a reflex.

When it went public in 2021, it didn’t just list a company.

It listed a habit.

Not just for grocery delivery. But for a new kind of question:

“Can I get this now?”

Groceries, medicine, chargers, ice cream. And yes, even birthday candles.

Not later. Now.

It wasn’t just an acquisition. It was an expansion of instinct.

Because when you already own dinner, planning, and cravings, adding urgency completes the circuit.

Zomato answered hunger. District answers indecision. Blinkit answers impatience.

Different products. Same playbook. One question at a time, Zomato is becoming the infrastructure behind your everyday decisions, the defaults you don’t even notice.

Most brands build features. The best ones build instincts.

These aren’t just apps anymore. They’re a mental operating system.

One that answers your appetite. Your plans. Your impatience.

We think we’re choosing. But more often, we’re just reaching for what’s already been decided.

The strongest companies don’t just win markets. They win minds.

Not by shouting. Not by discounting. But by answering questions before you even know you’re asking.

The next time you open an app without thinking, remember: someone earned that instinct.

That’s not a feature. That’s a Mental Market Monopoly.

Being First Isn’t Enough

Sometimes the story isn’t about who won.

It’s about who almost did.

Yahoo was once the homepage of the internet. MySpace had more users than Google. Premier launched a smokeless cigarette 20 years before the world was ready.

They all had traction. They had attention. Some even had a head start.

But they never became the default.

First-mover advantage is overrated, unless it leads to Mental Permanence. Because being first might get you noticed. But only mental dominance makes you unforgettable.

Why?

Being first gets you noticed. Being final means no one else gets considered. That’s the quiet power of a Mental Market Monopoly.

Yahoo helped people browse. Google rewired how people think.

MySpace hosted your profile. Facebook became your identity.

BlackBerry made you productive. Apple made you feel powerful.

Vine made you laugh. TikTok made you stay.

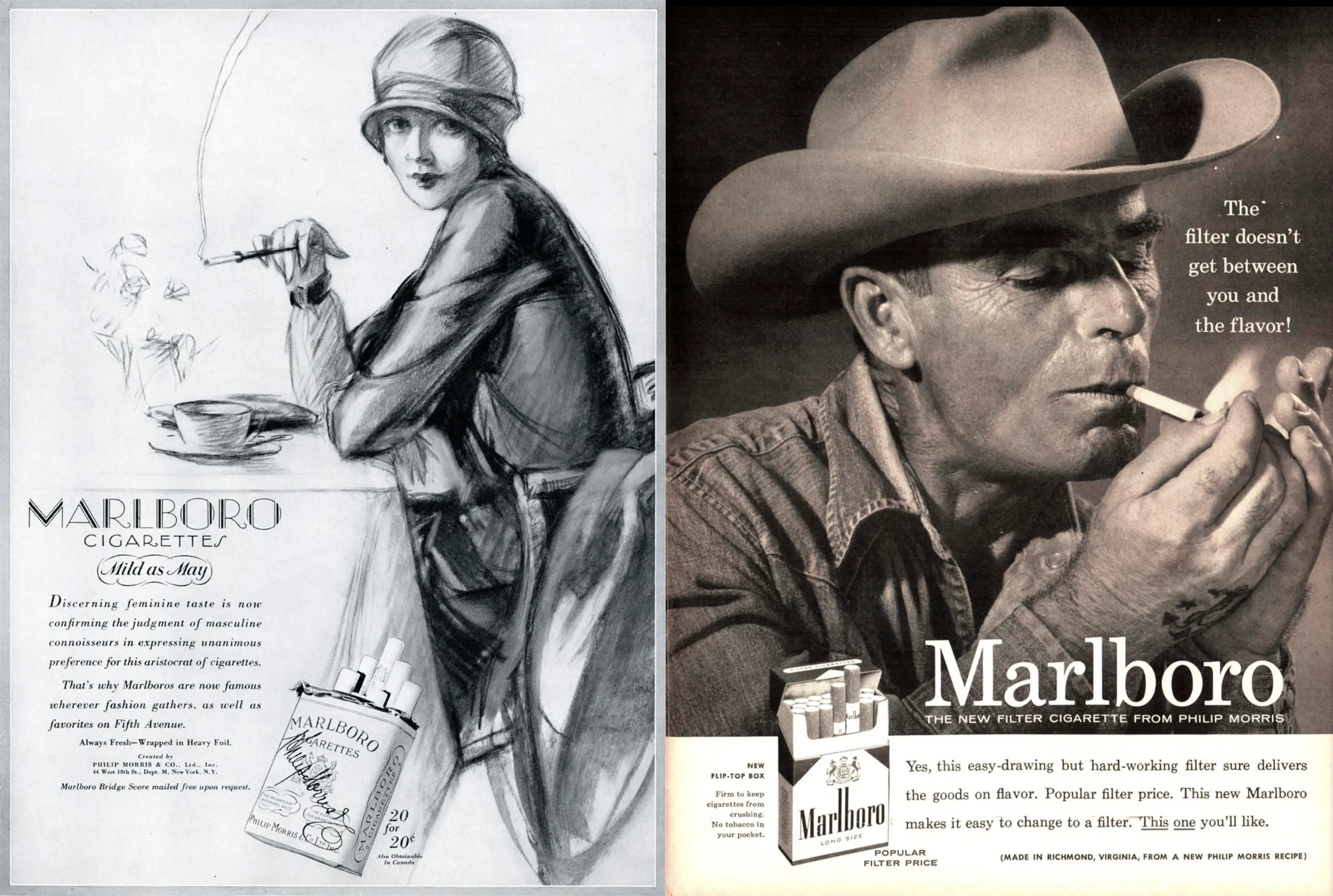

Premier was a breakthrough. Marlboro was a belief.

In 1988, R.J. Reynolds launched Premier, the world’s first smokeless cigarette. A technical marvel. No ash, no smoke, just nicotine vapor. It was decades ahead of its time.

But it failed. Because no one craved innovation that tasted like burnt plastic.

Across the street, Philip Morris didn’t innovate. They transformed perception.

Marlboro wasn’t always a cowboy brand. It started in 1924 as a cigarette for women, becoming “Mild as May.” But in the 1950s, filtered cigarettes were seen as weak. So Philip Morris rebranded Marlboro for men, not by changing the cigarette, but by changing the story.

They introduced the Marlboro Man: a stoic cowboy in an open field. No tagline. No pitch. Just a myth.

Premier engineered the future. Marlboro romanticized the past.

And when the product becomes a story, and the story becomes identity, there’s no contest. You don’t just smoke a Marlboro. You become the Marlboro Man.

Premier tried to change behavior. Marlboro confirmed who you already thought you were.

Guess who won?

The graveyard of near-monopolies is filled with companies that almost won the mind, before someone else won it more completely.

Not because the other brand shouted louder. But because it decided for you.

The difference between being known and being inevitable is invisible until it’s irreversible.

That’s the line most brands never cross.

Most die fighting for market share.

They die because they never earned your mind.

The Brand That Invented Santa In Your Mind

Why winning minds matter more than winning markets.

Coca-Cola didn’t just build a brand.

It built a shortcut in your brain.

Most companies fight for attention. Coca-Cola earned such familiarity that it became invisible.

In 1915, Coca-Cola did something subtle but brilliant: they designed a bottle so distinct you could recognize it in the dark, or even from a shattered piece on the ground. That shape became a symbol. The red and white became a signal. The cursive script became a memory.

They weren’t just branding. They were embedding.

First, they owned the bottle. Then, they owned the holiday.

In the 1930s, they did it again, this time with Santa Claus.

Back then, Santa didn’t have a dress code. Sometimes he wore green. Sometimes brown. His shape shifted too, from lanky and stern to lean and elf-like.

Coca-Cola gave him a makeover: a red suit, a jolly face, and a round belly. They hired illustrator Haddon Sundblom for a holiday campaign, and what he created wasn’t just a character. It was culture.

Over time, people stopped seeing Coca-Cola’s Santa as a marketing tool. They just saw Santa. The brand had reached that rare level of influence where its version of reality became reality.

That wasn’t an accident. It was a strategy.

You didn’t just see Coke, you felt it. You associated it with joy, celebration, summer, and family. With moments you never wanted to end.

And they didn’t stop at global campaigns. They went local.

In India, they didn’t just offer refreshment—they became the answer. With one simple line, “Thanda matlab Coca-Cola”, Coke didn’t just own the brand. They hijacked the language. “Thanda” (Hindi for cold drink) no longer meant cold drink. It meant Coke.

This was the brilliance: they didn’t force their way into culture. They blended into it until the brand and the behavior were indistinguishable.

Coca-Cola didn’t fight for attention. It created rituals. Moments. Associations. Hot summer days. Family holidays. Joy in a glass.

While other brands shouted, Coke whispered a feeling.

And once a brand lives in your head, it doesn’t need to convince you anymore. It just starts printing money behind your back.

That’s the quiet power of a Mental Market Monopoly.

You don’t choose it. You just reach for it, without even realizing why.

What If These Brands Disappeared Tomorrow?

Imagine waking up one morning and reaching for the world you know, only to find it gone.

You unlock your phone to check the route to work. But there’s no Google Maps. You know the address, but not the way. You hesitate. You scroll. You guess. And for the first time in years, you feel genuinely lost, not just directionally, but mentally. The quiet confidence that something will guide you has vanished.

At lunch, you tap on Zomato. Nothing. Swiggy? Also gone. You’re not just hungry, you’re indecisive. You can’t recall what’s good, nearby, or delivers. The decisions that used to take seconds now take mental energy. What once felt like freedom now feels like friction.

You tell a friend to “Paytm karo.” But they don’t understand. The phrase that once replaced “send me money” no longer holds meaning. You’re not just missing an app, you’re missing the cultural shorthand that made transactions effortless.

There’s no Uber. No WhatsApp. No Apple Calendar nudging you about the meeting you were about to miss. No Blinkit to grab groceries, cables, or ice cream in ten minutes. The background tools of life, tools you rarely notice, have gone silent.

And then it hits you: no iPhone. No MacBook.

What do you replace them with?

And more importantly, what doesn’t make everything worse?

Which phone still syncs smoothly with your laptop? Which laptop doesn’t change how you work? Which option doesn’t turn every little habit into a new decision?

This isn’t about features or pricing. It’s about friction. And friction, after years of seamless flow, feels like chaos. Suddenly, every action that used to feel automatic now requires effort. Every click is a question. Every decision has weight.

Because when something becomes second nature, replacing it doesn’t feel like a switch. It feels like a setback. Your brain resists the change, not because the alternative is bad, but because it’s new. Unfamiliar. Mentally expensive.

That’s what I call Cognitive Gravity, the mind’s tendency to cling to what feels effortless, obvious, and safe.

And that’s the most expensive switching cost of all, not money or time, but mental effort. You’re not just learning something new. You’re unlearning something old.

Financial costs can be negotiated. Functional costs can be trained away. However, mental switching costs run deeper, entrenched in habits, memory, and identity. The moment you have to stop and think, you’ve already lost some trust.

That’s what makes a Mental Market Monopoly so defensible. Not because the product is better, but because the mind doesn’t want to leave it behind.

Not dominance through ads or pricing. But through trust. Through ritual. Through emotional real estate so embedded in your day, its absence doesn’t just disrupt your behavior; it rewires your reality.

These brands aren’t just irreplaceable in function. They’re irreplaceable in feeling.

You can build a cheaper phone. A better-designed app. A faster search engine.

But if people don’t feel anything when they use it, they’ll return to the ones that do. Because once a brand becomes the default in your mind, it doesn’t just win your attention—it earns your trust.

And trust, at scale, isn’t just loyalty.

It’s margin.

It’s retention.

It’s the quiet engine behind the most valuable balance sheets in the world.

From Mindshare to Market Cap

In 2023, Apple held over $160 billion in cash and marketable securities.

People still debate whether the next iPhone is worth it. Specs are dissected. Prices are questioned. Critics say it’s incremental, not revolutionary. And yet, millions line up to buy it. Not because they’ve done the math. But because they don’t feel the need to.

The product doesn’t have to surprise them. It just has to show up and work the way their life expects it to.

That’s the quiet force of a Mental Market Monopoly: when belief becomes muscle memory, and purchase becomes instinct.

Google holds over $120 billion in cash.

Not because it’s the best search engine, but because it’s the only one your brain remembers to open.

Microsoft, once dismissed as boring, now sits in the bloodstream of work and life. Its tools don’t ask for attention. They don’t need proof. They need predictability. And they earn over $100 billion for it.

These aren’t just successful companies. They’re subconscious ones.

Most companies spend to stay relevant. These brands don’t need to. They’ve already earned the one thing money can’t buy: your unthinking trust. Because once you’re in the head, you’re in the wallet.

Not because you shouted louder. But because you became the answer to a question no one realized they were asking.

That’s what Coca-Cola understood long before Google. You didn’t have to think it was the best soda. You just had to believe there was no better time for it, when the sun was high, the bottle was cold, and someone said thanda.

It’s what Zomato is building now. Not just a food app, but a reflex. A rhythm. A planner for modern life.

These brands didn’t just win the market. They made you forget there was a market at all.

Like Coke did with thanda.

Like Apple did with phone.

Like Google did with search.

They didn’t just build products. They built expectations.

And expectations are more complex to compete with than features, because they live in your instincts, not your inbox.

That’s not just marketing. That’s inevitability.

That’s a Mental Market Monopoly, the quietest engine of wealth the world has ever known.

Because you can’t win the mind with features alone.

You need meaning.

You need memory.

You need to matter.

In the end, the most powerful brand isn’t the one people admire.

It’s the one they stop noticing because it’s already there, in their mind, ready to take hold as they think of the question. Embedded. Trusted. Unquestioned.

In the next essay, we’ll unpack how to build one.