Learn why Big Ideas in advertising don’t work anymore and how modern marketing uses remixable content, fandom loops, and cultural gravity to win.

For decades, the Big Idea in advertising was considered a kind of cultural superpower: one bold concept that could launch a product, define a brand, or even spark cultural obsession. From Mick Jagger to MTV, to Volkswagen “Think Small,” to Marvel spending hundreds of millions to own opening weekend, these campaigns worked because the world was still paying attention. But that world is gone, replaced by fragmented feeds, participatory media, and a constant battle between signal and noise.

This essay unpacks why Big Ideas stopped working, what broke behind the scenes, and how effective marketing today doesn’t start with a slogan. Modern marketing trends rely less on control and more on participation. It starts with sparks, signals, and cognitive gravity.

How the Big Idea Once Ruled Advertising

In the spring of 1982, MTV was failing. The network had launched the year before with the defiant burst of "Video Killed the Radio Star" , but hardly anyone noticed. Only about a quarter of American cable households could even access it. Cable operators resisted carrying it because they saw no demand. Music executives dismissed it as fluff, even a threat to record sales. Advertisers didn’t want a channel aimed almost entirely at teenagers, who were considered too broke to matter. Even the programming betrayed its weakness: a loop of a few hundred videos, mostly from scrappy British bands, played over and over until MTV felt like a broken record stuck on repeat.

Then came a line that cut through everything.

Mick Jagger appeared on television, leaned into the camera, and barked:

I Want My MTV!

It was a strange thing for a rock star to demand. Yet within weeks, teenagers across America picked up their phones and repeated the line word for word. Local operators were overwhelmed by calls. Artists who once sneered at videos suddenly begged to be included. Practically overnight, MTV went from joke to juggernaut. By the end of its second year, subscriptions had tripled from three million to nine million households.

Why did that single line work? Because it was absurd enough to stick, spoken by an authority figure teenagers admired, and easy to mimic. Absurdity, authority, and mimicry formed a kind of marketing psychology, one that relied on social proof, emotional resonance, and repetition.

The magician behind it was George Lois. Years earlier, Lois had convinced baseball legends Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra to do something equally absurd. He told them to grimace at the camera and shout: I Want My Maypo!

They were selling oatmeal. Sales rose an average of 78 percent and reached as high as 186 percent in some markets, according to Sponsor Magazine.

The same device that made porridge desirable made MTV indispensable. Lois recycled the trick, only this time he swapped Mantle for Jagger and breakfast cereal for pop culture. It worked just as magically.

MTV’s collapse, and sudden turnaround was one of the last great victories of the Big Idea in advertising. The kind of campaign that could change consumer behavior, drive cultural marketing, and alter an entire generation’s taste in music.

The Rise and Reign of Big Ideas in Advertising

The Big Idea in advertising was never just about creativity. It was about commanding attention. And for decades, that attention was unified.

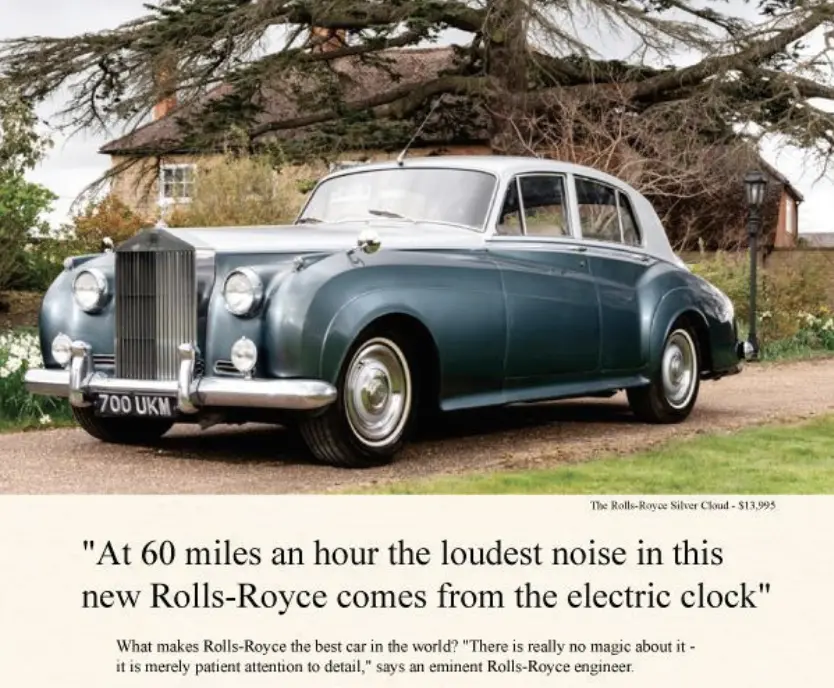

David Ogilvy believed advertising should read like journalism. His Rolls-Royce ad began:

“At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock.”

It was factual, clever, and impossible to forget.

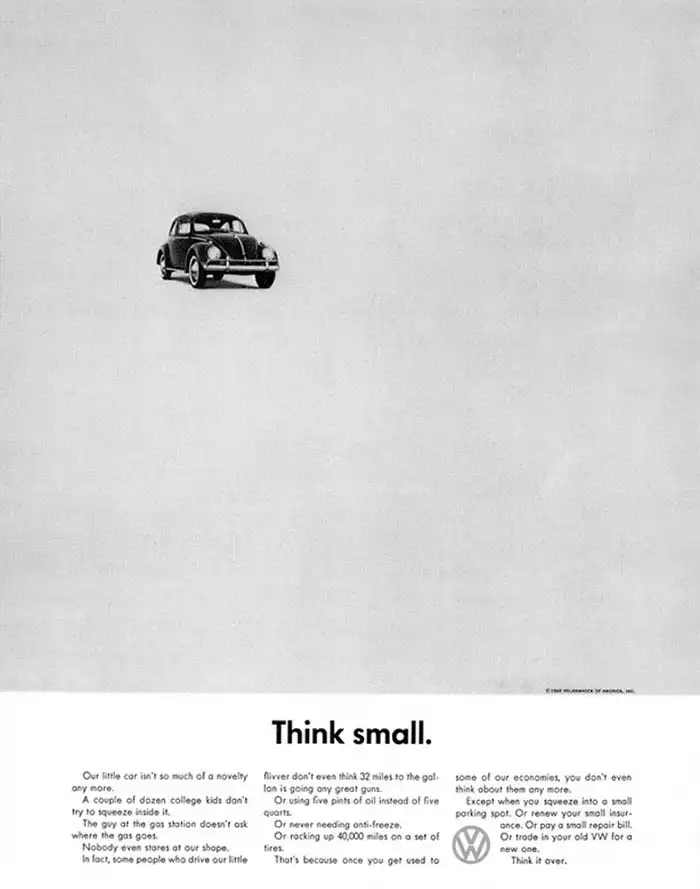

Bill Bernbach broke every rule of car advertising. His “Think Small” campaign for Volkswagen placed a tiny black-and-white Beetle in a sea of white space. What should have been a liability, a modest German car in postwar America, became a national charm. Volkswagen’s U.S. sales quadrupled in the decade that followed.

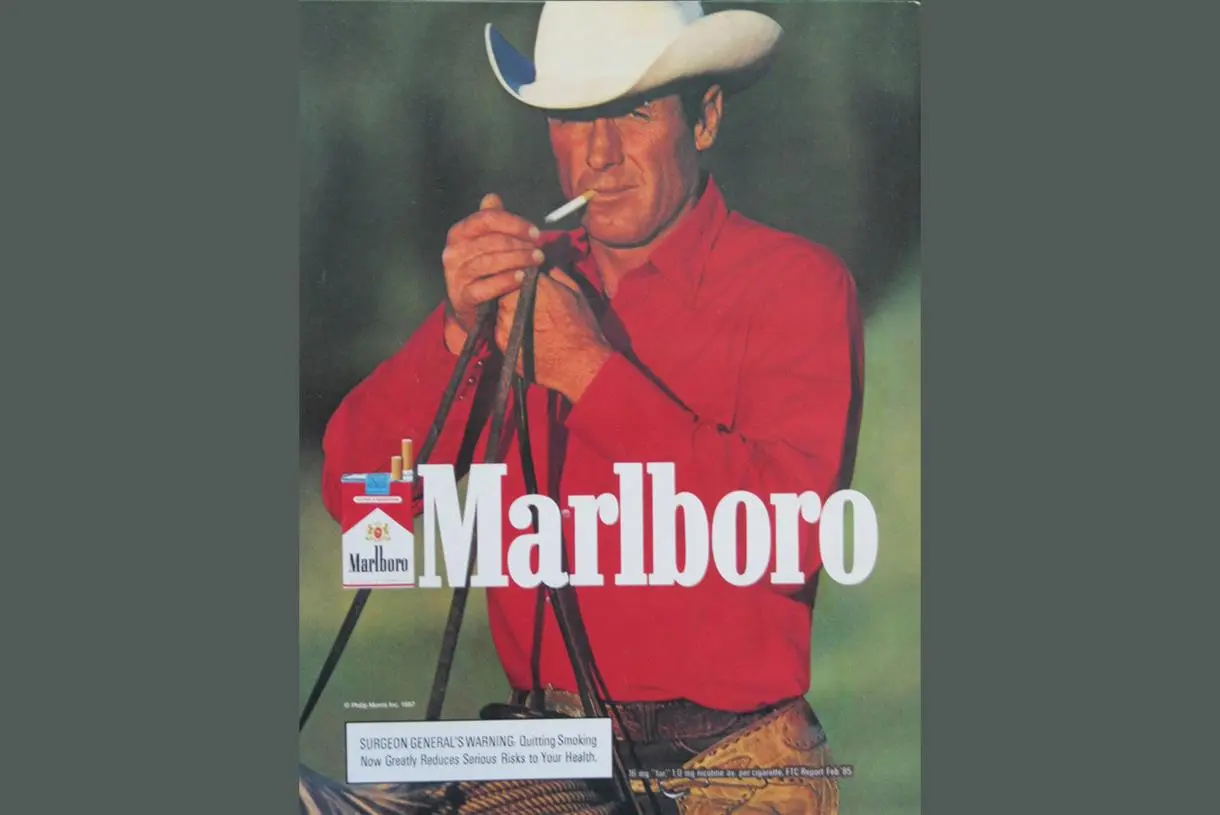

Leo Burnett built characters that seemed to step off the page and into American life. The Marlboro Man turned cigarettes into a rugged social symbol. Tony the Tiger became more than a mascot; he was a voice children still remember. These were early examples of brand storytelling using characters, copy, and cultural symbols to craft a memory, not just deliver a message.

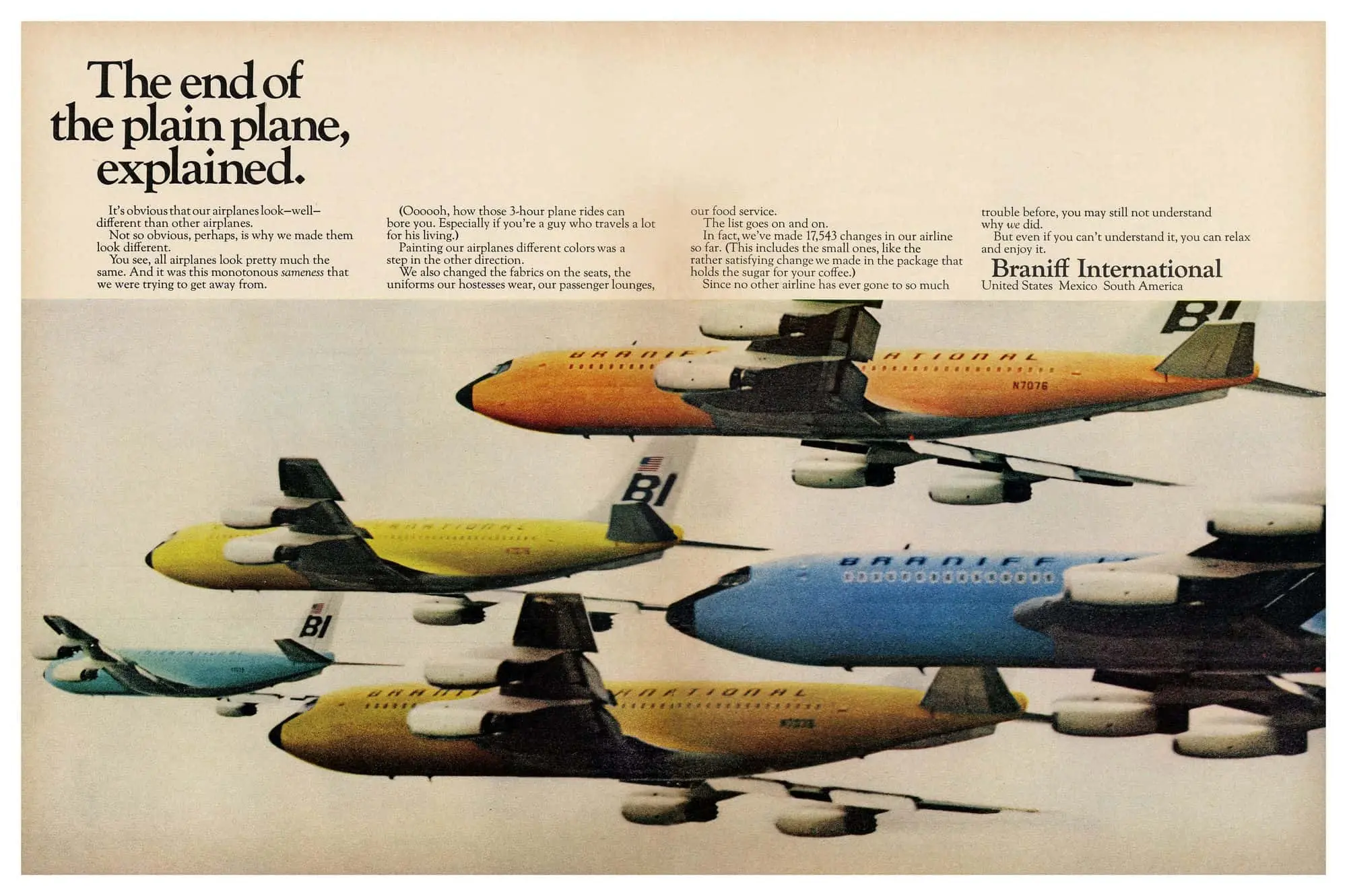

Mary Wells Lawrence went further, transforming Braniff Airways into a theater. She dressed planes in bold colors, dressed attendants in couture, and sold not flights but a lifestyle.

These campaigns worked not just because they were clever but because everyone was watching the same thing at the same time. In the 1960s, three networks captured nearly 90 percent of all U.S. viewers. Ads weren’t something you could skip. They were part of the show. A single phrase could ripple across these television networks, every magazine rack, and the radio dial. Advertising had the rare advantage of a captive, synchronized audience.

Put simply, a Big Idea was a single, unforgettable concept that spread because everyone saw it at the same time.

The Fragility of the Big Idea in Advertising

If Big Ideas were so unstoppable, why did some fail?

In 1985, Coca-Cola tried to reinvent itself. The company spent $4 million on research and millions more on rollout, certain the world would follow. Instead, the backlash was immediate. Within weeks, the company received more than 400,000 complaint calls. People hoarded the old formula. Protest groups formed. The campaign collapsed within months.

It showed, for the first time, that consumers could organize against a brand even without the internet. Nostalgia, not taste tests, was the hidden driver of loyalty.

Decades later, Pepsi repeated the mistake with its infamous Kendall Jenner “Live for Now” ad. What was meant to be a unifying gesture of protest and peace became a cultural punchline, accused of trivializing activism. The backlash was swift, global, and unforgiving.

Big Ideas could electrify culture, but only when the audience was willing to play along. When they misjudge the mood of their audience, these big ideas fail. Coke underestimated the grip of nostalgia. Pepsi underestimated the seriousness of the protest. Both misunderstood audience behavior. They assumed the mass media era still held sway, when in truth, cultural fluency had already shifted.

Together, these failures reveal the hidden weakness of the Big Idea. It was never just about creativity or scale. It relied on something more fragile: a mass audience willing to accept the premise. When the mood of that audience shifted, even the boldest campaigns collapsed. And in a fragmented modern marketing landscape, that kind of unity is almost impossible to find.

Why Traditional Advertising Doesn’t Work Anymore

Traditional advertising thrived on three conditions: a captive audience, predictable attention spans, and mass reach. All three have vanished.

- Fragmentation.In 1960, nearly 90 percent of Americans watched the three major networks. By 2020, even the most-watched shows drew less than 10 percent of the population. The stage for a Big Idea simply doesn’t exist anymore.

- Speed.The thirty-second spot once felt natural. Now Reels, Shorts, and TikToks thrive on loops under fifteen seconds. These platforms aren’t shortening attention spans by accident, they are engineered to reward constant novelty. One big story is no match for a feed that refreshes every swipe.

- Economics.CPMs (cost per thousand impressions) have fallen, but the volume of impressions brands need has exploded. Instead of one brilliant idea that runs everywhere, brands are trapped in an addiction to constant output.

The Big Idea didn’t die from lack of imagination. It died because the hidden condition that powered it, a unified, captive audience, disappeared. In the UK alone, £20 billion is spent annually on advertising. Of that, 89 percent goes unnoticed, 7 percent is remembered negatively, and only 4 percent is remembered in a positive way.

Why Even Hollywood Can’t Manufacture Culture Anymore

The clearest evidence lies in Hollywood.

For decades, a studio could buy culture. A hundred million dollars spent on trailers, billboards, and television spots almost guaranteed an opening weekend.

Now even Marvel struggles. The Fantastic Four: First Steps partnered with household names like Little Caesars, General Mills, and Pop-Tarts. The rollout was everywhere, styled in a retro-future aesthetic. The campaign cost nearly $170 million on top of a $200 million production budget. Yet the film will likely finish below $600 million worldwide, far short of its $850 million break-even mark.

Blockbusters now spend as much on promotion as on production, only to be ignored if they miss the cultural pulse. Earned media, the kind sparked by memes, fan edits, reaction videos, and TikTok remixes, often outperforms campaigns with ten times the budget. When the story doesn’t invite participation, it disappears.

In marketing terms, earned media is exposure you don’t pay for, but generated when people want to share, not when you ask them to.

The problem isn’t just one film. Streaming has rewired audience behavior. Many fans now “wait it out” for Disney+, Netflix, or Amazon Prime rather than rushing to theaters. Global releases are staggered, which kills the idea of a single cultural event. And costs have ballooned, blockbusters now spend 50–100 percent of their production budget on marketing. The customer acquisition cost for a single movie ticket has never been higher.

If Marvel, with billions in marketing muscle, can no longer guarantee success, then the age of buying culture is truly over.

How Culture Now Moves: Memes, Fans, and Word of Mouth

Culture no longer follows command. It follows chaos.

And in that chaos, the most effective strategies are no longer mass marketing campaigns, but cultural marketing tactics that evolve through word of mouth.

Barbenheimer began as a joke, and became a phenomenon. For(2025), 45 percent of the opening weekend audience came through word of mouth, not marketing. McDonald’s Grimace Shake became a perfect example of meme marketing, driven not by strategy, but by TikTok users turning it into a strange, chaotic running gag. Duolingo’s green owl went from mascot to internet personality, shaped as much by fans as by the brand.

Why do these spread? Because memes reward participation. People share them not because brands tell them to, but because sharing signals belonging. It makes them feel clever, “in on the joke,” part of a tribe. Every remix adds momentum. This is the core of creator culture and participatory media: one template spawns thousands of remixes, each personalized, each pulling in new audiences.

The lesson: what succeeds now is not a finished message but an unfinished template people want to play with.

And it is not just Hollywood. The same fragility applies to small businesses and global startups alike. A local coffee shop, a new delivery app, even a neighborhood pizza brand face the same volatile math of attention. A single spark may change everything, but no one can predict which spark will catch.

Word of mouth is no longer a happy accident. It is the highest return on investment any marketer can hope for. But it cannot be scripted. The job now is not to dictate outcomes but to create conditions where culture has something to grab onto.

From Unforgettable to Unmissable: How Marketing Goals Have Shifted

For half a century, the Big Idea was advertising’s empire. One phrase could turn oatmeal into a craze, a car into a cult, or a television channel into the pulse of youth culture.

That empire is gone.

The question has changed. It is no longer how to make something unforgettable. It is how to make it unmissable.

Because no one audience is captive anymore. The internet fractured attention. TikTok shortened its span. Algorithms made culture unpredictable. The old stage that once carried a Big Idea has split into thousands of rooms. Too many screens, feeds, and competing voices.

This shift, from message control to cultural participation, is exactly why Big Ideas don’t land anymore. What used to be a single cultural moment is now a swarm of micro-moments, spread across time zones, formats, and feeds.

Today, marketing strategy isn’t about perfect clarity or top-down control. It’s about cultural relevance, emotional resonance, and choosing signal over noise. The ideas that spread are rarely polished. They are unfinished invitations. Templates, not taglines.

If the Big Idea was a speech, today’s marketing is a conversation: open-ended, responsive, and built with the crowd. What works now isn’t one perfect slogan but a series of sparks:

• Memes that invite remixing

• Fandom loops that grow without permission

• Cultural signals that people want to align with

• Participatory media that rewards the crowd for taking part

The modern marketing trend isn’t about dominance. The phrase ‘cognitive gravity’ describes this exact shift: when ideas pull culture toward them through emotional and social mass, not sheer volume.

What Replaced the Big Idea in Modern Marketing? 5 Cultural Mechanics That Work Today

Big ideas have been replaced by cultural gravity: a strategy built on remixable content, emotional stickiness, and fan participation. In an age of fragmented attention, brands succeed not through dominance but by becoming unmissable. The goal is no longer clarity, but cultural relevance and spread.

- Meme Loops– Open-ended formats that invite remixing and personal expression.

- Fandom Participation– Fans create content, spread emotion, and defend the brand.

- Cultural Timing– Campaigns that hit the right cultural moment (e.g. Barbenheimer).

- Earned Media– Sharing driven by users, not marketers.

- Emotional Stickiness– Signals that make people feel something—enough to share.

TL;DR: Why Big Ideas in Advertising No Longer Work

- Big Ideas worked when the audience was unified and attention was scarce.

- Today, that audience is fragmented, fast, and algorithm-fed.

- Mass media no longer guarantees belief, buzz, or behavior.

- Culture now moves through memes, fandom, and remixing, not slogans.

- Modern marketing is about gravity, not dominance.

In Part Two, we’ll explore the strange new playbook that has replaced the Big Idea: how memes spread faster than media buys, how fandom loops turn audiences into advocates, how collaborations blur the line between brand and culture, and how improvisation has quietly become the most powerful marketing skill of all.

Because the future of marketing isn’t about commanding attention. It’s about creating gravity.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Big Idea in advertising?

A Big Idea is a powerful central concept or slogan that drives an entire campaign, a single, unforgettable phrase or concept that once dominated culture, like “I want my MTV” or “Think Small.” It worked because everyone saw it at the same time.

Why don’t Big Ideas work in marketing anymore?

Because today’s audiences are fragmented, unpredictable, and fast-moving. The unified stage that once supported a bold message no longer exists.

What replaced the Big Idea in modern marketing?

Memes, fandom loops, remix culture, cultural relevance, and word of mouth. These don’t need permission. They just need momentum.

What’s the modern alternative to Big Ideas in marketing?

Instead of one perfect concept, marketers now create conditions for cultural gravity: remixable content, collabs, memes, and emotional resonance that spreads organically.

What is earned media?

It’s organic publicity driven by people, not ad budgets, like viral TikToks, fan-made edits, or memes. It travels farther because it feels real, not rehearsed.

What is cognitive gravity in marketing?

It’s the quiet power of an idea to pull attention without demanding it. Cognitive gravity creates participation instead of interruption, and it draws culture toward you.

Do traditional ads still work at all?

Yes, but only when combined with earned media, creator collabs, and community-driven formats. Old-school ads struggle alone in today’s fast, fractured attention economy.

What are examples of marketing gravity in action?

The Barbenheimer meme, Duolingo’s chaotic TikTok voice, and MSCHF’s viral drops all succeeded not because of one big ad, but because people carry them forward.

.webp&w=3840&q=75)