An associate once asked John D. Rockefeller why he took such big risks. He replied with something so simple that it should belong on a motivational poster.

Rockefeller said:

“Because small risks make small men.”

I think about that a lot.

Why Playing It Safe Feels Smart

Most business risk strategy advice emphasizes caution. It prioritizes risk management and predictable outcomes over breakthrough innovation.

“Be careful.”

“Don’t overextend.”

“Plan for what can go wrong.”

This is what you hear from your best clients, your closest friends, even the experts online.

And they’re not wrong.

Most plans that need a miracle fail.

Nine out of ten drugs that enter clinical trials fail to reach approval. Most funded startups don’t work out. Most “sound” bets on innovation end up looking naïve in hindsight. The number, no matter the industry, stubbornly hovers around nine out of ten.

Rockefeller wasn’t bragging. He wasn’t being reckless. He was explaining. Look closer and you’d see it was all mathematics.

Florence’s Dome: The Original Miracle Bet

In the 1400s, Florence wanted a cathedral dome larger than any built since antiquity. They poured money into it, laid the foundations, raised the walls. But they had one problem no one could solve.

The dome was too big. Too heavy. The span was so vast that no one alive knew how to build it without it collapsing under its own weight. There was no wooden scaffold strong enough. No engineering textbook has the answer. The cathedral sat unfinished for decades, a half-completed monument to human ambition exceeding human ability.

Filippo Brunelleschi, a Florentine architect, engineer, and designer, proposed something that sounded absurd. But he refused to share full details in advance, forcing the city to trust him or abandon the dream.

Florence chose to bet on the miracle.

And it worked. Brunelleschi built the largest masonry dome ever, without traditional scaffolding. His plan used herringbone brickwork to lock itself in place as it climbed higher, like a snake swallowing its own tail.

It was the ultimate high-risk, high-reward bet: a city staking its future on an idea with no guarantee.

The dome still stands 600 years later. It remains one of the world’s great engineering feats. But it only exists because the city leaders were willing to take a bet on the impossible problem, and back the person who said he could solve it, even if they didn’t understand how.

I wonder how many of us would have had the nerve to back him.

What Is the Miracle Strategy?

The Miracle Strategy is a deliberate innovation strategy to take high-risk bets that seem impossible, understanding that most will fail. Still, the rare successes will be so transformative that they justify all the failures. It’s designed to capture an asymmetric payoff.

It’s not safe. It’s not guaranteed. But it’s the only way to do something so remarkable that people will talk about it centuries later.

Big outcomes don’t come from cautious bets. Small risks, by design, limit your upside. They keep you safe, but they keep you small.

This is the part of the strategy no one wants to talk about, because it’s scary. We like to imagine a world where results are purely the function of good planning, rational analysis, and predictable execution. The truth is that most outcomes, especially the really extraordinary ones, require a leap that feels reckless in the moment.

Not Blind Hope, Not Pascal’s Scam

It’s important to be clear about what this is not.

It’s not what some call Pascal’s Scam, betting on something wildly improbable just because the potential reward is infinite. That’s not a strategy. That’s gambling on fantasy.

The Miracle Strategy is different.

It’s about making hard, risky bets on ideas that are uncertain, but possible.

It demands a plan. Talent. A real mechanism for making it work. It accepts that most bets will fail, but that one success can pay for them all.

It’s not about hoping things work out. It’s about doing the work that makes a miracle possible.

Of course, this strategy has a dark side. It isn’t foolproof. Sometimes, big bets blow up in your face.

Katzenberg and the Price of High-Risk Strategy

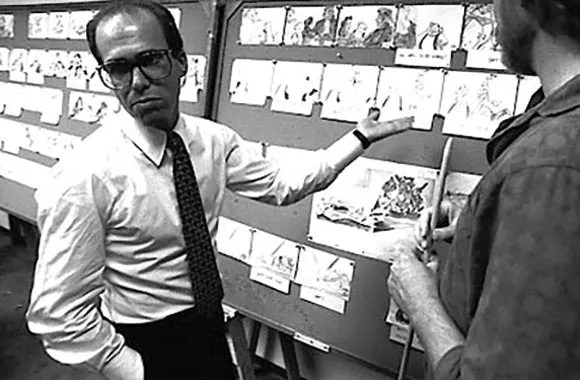

Jeffrey Katzenberg joined Disney in 1984 as chairman of Walt Disney Studios. At the time, Disney animation was on life support. The studio that invented the feature-length cartoon was struggling to get audiences to care at all.

Katzenberg bet big. He pushed budgets higher, recruited fresh talent, fought brutal internal politics. He greenlit The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King. One after another, record-shattering hits. It wasn’t careful or cautious. It was a total reinvention, a bet that audiences still wanted animated musicals if they were done brilliantly.

Katzenberg’s approach was pure strategic risk-taking, betting big budgets, new talent, and his own reputation.

It worked brilliantly.

But not for him.

At the height of that success, Katzenberg wanted more. When Disney’s president, Frank Wells, died in a helicopter crash in 1994, Katzenberg expected to be promoted to Wells’s position. Michael Eisner, the CEO, refused. The board sided with Eisner, who reportedly disliked Katzenberg's aggressive, sometimes abrasive management style and saw him as a rival.

Katzenberg’s ambition, the very trait that saved Disney animation, now made him look dangerous. So they forced him out.

One of the most successful executives in Hollywood had to clean out his office.

That’s the other side of the Miracle Strategy. The risk isn’t just financial. It’s personal. Success can breed resentment. Bets that make you indispensable can also make you threatening.

Sometimes, betting big builds the empire.

Sometimes, it gets you fired.

And there’s another wrinkle people forget about the Miracle Strategy.

The real danger isn’t only failure. It’s what success does to your mind.

The Psychological Risks of Success

Early wins can breed overconfidence. You start believing you have the magic touch, that every crazy idea will work out just like the last one. So you double down again and again.

Or it makes you cautious. Careful. Afraid to risk what you’ve built. That’s loss aversion: protecting what you have even at the cost of what you could get.

Even the smartest investors fall into this trap.

Bill Gurley, one of the most respected venture capitalists in Silicon Valley, has talked openly about why he passed on Google in 2002. On paper, it was full of “red flags”:

- Search didn’t look like a good business. Yahoo’s stock had collapsed. Excite was going bankrupt.

- Two PhD founders insisting they’d be good first-time CEOs, a classic risk many VCs avoid.

Gurley says they just “didn’t lay chase.” They didn’t even fight for the deal. It felt safer to walk away.

In hindsight, he calls it the perfect lesson in asymmetric payoff. As he puts it: “You can only lose one time your money. And in a case like Google, you make, what? 10,000 times your money.”

It feels rational to avoid messy, uncertain bets that could fail spectacularly. But playing it safe doesn’t just mean missing one deal. It means missing the deal that pays for everything else.

That tension is what makes the Miracle Strategy so hard to stick with. You have to see possibilities where most people see red flags. You have to accept that the biggest upside often hides behind the scariest risk.

The irony is that both overconfidence and loss aversion come from the same place: success. It changes how you see risk. Even if you embrace the Miracle Strategy once, you might not know when to do it again.

They’re two sides of the same trap: overconfidence makes you reckless, while caution makes you timid.

When Should You Bet Big?

You have to know when a giant bet is reckless, and when it’s necessary.

Because history is full of people who ignored Loss Aversion and changed everything.

Apollo Program, Genome Project, and Steve Jobs

The Apollo Program cost over $25 billion in 1960s dollars. Critics called it an obscene waste, a flag-planting stunt. But it didn’t just put humans on the Moon. It accelerated computing, materials science, and systems engineering. It trained a generation of scientists who went on to build the modern world.

The Human Genome Project cost $3 billion. It was mocked as science fiction for nerds. Today, gene sequencing is fundamental to modern medicine, cancer treatment, and even tracking new pandemics.

And then there’s Steve Jobs.

He’s the go-to example for this kind of risk, which is almost unfair because he made it look deceptively easy.

After the iPod became a cultural phenomenon, Apple could have coasted. Protected its margins. Fended off competitors just enough to keep the cash flowing. That would have been the safe move. The rational move.

Instead, they killed their own golden goose.

Jobs insisted on building the iPhone, a device that would make the iPod obsolete. Internal teams pushed back. Analysts thought he was crazy. Why destroy the thing everyone loved?

But Jobs understood something uncomfortable: if you’re too afraid to disrupt yourself, someone else will be happy to do it for you.

It wasn’t logical by normal business standards. But it was the only move that gave Apple a shot at being more than just the “iPod company.”

These are all versions of the Miracle Strategy.

Each of these was an asymmetric risk: risking massive resources for a payoff that could change the world.

They weren’t guaranteed to work. In fact, they looked insane at the time. But they share one thing in common: they accepted that truly big goals demand risks no spreadsheet can justify.

It’s easy to see in hindsight. Harder when you’re in the room deciding whether to spend the money, burn the bridges, and place the bet.

Still, it’s worth asking:

Why would Florence want the biggest cathedral in the world? What for? To pray? You can do that in a modest chapel. Was it worth bankrupting a city for a dome?

Why spend billions putting a man on the Moon? Sure, we can list the technological spin-offs in hindsight—computing, materials science, systems engineering. But at the time? It looked like flags and dust. A giant bill for bragging rights.

Why would a celebrated director like James Cameron, after hits like The Terminator and Titanic, disappear for years before making Avatar? He could have cranked out safe sequels. Taken easier wins.

James Cameron’s Bet on Avatar

The truth is, Cameron conceived Avatar in the mid-90s, before Titanic. But the technology to bring it to life didn’t exist yet. So he put it on the shelf and made Titanic instead.

That was his “small” bet. Still risky, but achievable. It didn’t just succeed spectacularly. It taught him the very techniques he’d need later: realistic water effects, seamless CGI integration, immersive design. paid for in money, credibility, and hard-won experience.

So when he finally returned to, he didn’t just have the budget. He had the blueprint to reinvent filmmaking itself. He spent over a decade developing new technology just to tell a story about blue aliens. He risked hundreds of millions on 3D cameras, CGI worlds, and unproven visual effects. It was expensive, slow, and by Hollywood standards, unnecessary.

As Cameron himself put it:

“If you set your goals ridiculously high and fail, you’ll fail above everyone else’s success.”

James Cameron’s decision was entrepreneurial risk at the scale of blockbuster filmmaking. But that bet gave him something no one else had: the biggest film in history at the time, and the ability to define what movies could look like for the next generation.

It’s tempting to think this kind of bold, high-risk strategy is just for visionary directors or Silicon Valley founders. But the truth is, this tension between caution and daring has shaped entire civilizations.

Needham’s Question: China, Europe, and the Willingness to Risk Being Wrong

During World War II, the British government sent Joseph Needham, a Cambridge biochemist turned historian, to China to help maintain scientific exchange. He fell in love with Chinese history and technology, and was astonished by what he found.

He spent years cataloguing his enormous multi-volume work. But one question haunted him. It defined his life’s work and became known as Needham’s question:

When, how, and why did the Chinese empire lose its position of scientific and technological superiority to the West?

China was ahead for centuries in practical technology: paper, printing, the compass, gunpowder. But its culture prized stability. It valued mastery of the known. The goal was to perfect existing knowledge, not question its foundations.

Europe, for all its chaos, bet on uncertainty. On asking questions that had no clear answers. On systematic experimentation that could fail spectacularly.

It was a cultural willingness to in order to discover something new.

That’s the Miracle Strategy at the scale of history.

It’s the same tension we face in our own decisions today.

Most of us aren’t building cathedrals, launching to the Moon, or killing our own billion-dollar products.

So what do you do with this idea?

How do you make “The Miracle Strategy” usable without betting your entire company, your career, your reputation on one giant roll of the dice?

Applying the Miracle Strategy in Your Own Work

There’s a clue in an experiment run by Jerry Uelsmann, a photography professor at the University of Florida in the 1970s. At the start of the semester, he split his class into two groups.

One group would be graded purely on quantity. They just needed to produce 100 photos by the end. The other group would be graded on quality. They only had to deliver a single, perfect image.

You’d think the quality group would produce better work. But the quantity group won. Over and over.

Because by shooting constantly, the quantity group learned faster. They took more risks. They experimented, failed, and adapted.

That’s a small-scale Miracle Strategy.

It’s about making many, cheaper bets. Creating a system that rewards you for:

- Trying

- Failing

- Learning

- Trying again.

Because not every bet has to be a moonshot.

But you have to be willing to make the bets.

Even the big bets that fail aren’t wasted.

Jeffrey Katzenberg got pushed out of Disney, the studio he had saved. Most people in Hollywood assumed he’d lie low, nurse his grudges, maybe take a comfortable producing gig.

Instead, he did something harder: he doubled down.

In 1994, Katzenberg co-founded DreamWorks with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen. Three big personalities, each with something to prove. They wanted to build a studio from scratch, something no one had successfully done in decades.

The idea was audacious: compete head-on with Disney in animation, live-action, and music. Create an entertainment company that could rival the biggest players in Hollywood.

One of their first animated projects was a strange, irreverent fairy tale about an ogre named Shrek.

On paper, it didn’t look like a sure thing. It mocked the very fairy-tale formulas Katzenberg had perfected at Disney. The humor was weirder. The tone was cynical. The main character was a green swamp creature who didn’t care what anyone thought of him.

But that was the point.

Shrek was Katzenberg’s way of proving there was room for something different, stories that didn’t fit the Disney mold.

It worked.

Shrek became a cultural phenomenon. It won the first-ever Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. It made DreamWorks Animation a real contender.

And it happened because Katzenberg was willing to bet again after failure.

That’s the part people forget about big risks:

The same ambition that gets you fired can build something bigger the next time.

Not every organization can take moonshot bets, but every team can adopt a calculated risk mindset.

Why Betting Big Creates Cultural Gravity

That’s why you build the biggest cathedral in the world.

An oversized dome doesn’t produce food. It doesn’t defend against armies. It doesn’t generate trade. To a strict economist, it’s wasteful vanity, a monument to ego and excess.

That’s the safe view. The rational view.

But Florence wasn’t just competing for wool merchants or banking clients. It was competing for attention. For talent. For the best artists, architects, thinkers, and traders. A city that dared to do the impossible sent a clear signal to the world: this is where greatness happens. This is where you want to be.

The dome wasn’t just a roof. It was Florence’s magnet for talent.

When they backed Filippo Brunelleschi’s untested, borderline insane plan with no traditional scaffolding, they weren’t buying stone and brick. They were buying the story of Florence as the center of human possibility.

For generations, the dome didn’t just house prayers. It attracted genius. It gave Florence a gravitational pull. Michelangelo. Leonardo. Botticelli. The Renaissance itself needed a stage, and Florence built it.

The Miracle Strategy isn’t just a disruptive strategy. It’s an invitation to rethink decision-making under uncertainty.

It’s easy to dismiss big risks as indulgent or foolish. But playing it safe has its cost: it repels ambition. It breeds complacency and trades possibility for predictability.

The real danger isn’t just failure. It’s forgetting how to bet at all.

The better question isn’t “Will it work?” but “If it works, how big could it be?”

That’s the shift. From protecting what you have to imagining what you could make possible.

Because these bets offer asymmetric payoff. You risk losses you can survive to unlock gains that can change everything.

The Miracle Strategy is messy, expensive, and uncomfortable. It demands risking being wrong.

But that’s precisely what moves the world forward.

It’s not about getting an immediate return. It’s about making people look up and say, I didn’t know that could be done.

The real payoff isn’t just what you build. It’s the belief you create. The gravity you generate.

You see it in real numbers:

- Cameron’s Avatar 1 and 2 are two of the three highest-grossing movies ever worldwide, combining for over $5 billion.

- The iPhone has generated more than $1.5 trillion in revenue since 2007.

- Google turned early VC bets into returns hundreds, even thousands, of times the original investment.

That’s the signal you send to the world: if this is possible, maybe anything is.

“The world is a malleable place. If you know what you want, and you go for it with maximum energy and passion, the world will often reconfigure itself around you much more quickly and easily than you would think.” — Marc Andreessen

That’s the promise of the Miracle Strategy.

And it connects to other ideas about how big, high-risk bets don’t just succeed individually, but reshape the entire world:

- Cognitive Gravity is the psychological resistance that keeps people locked into old assumptions and familiar choices. It’s the force that makes markets slow to change. The right bold move, an unexpected bet, can break that gravity, shifting what people see as possible.

- Mental Market Monopoly is a branding strategy where your product, service, or idea becomes the default choice in the consumer’s mind. It’s not just about market share. It’s about owning perception. When a brand achieves a Mental Market Monopoly, it turns big, defining bets into lasting positioning advantages competitors struggle to dislodge.