In 1987, the FDA approved a little blue-and-white capsule called Prozac. Scientists declared victory over depression. Newsweek ran a cover story. Millions of prescriptions flooded pharmacies. The brain, they said, had finally been cracked. But although the drug changed everything, it still wasn't enough.

Thirty-seven years later, we are still waiting for that promise to be kept.

TL;DR

- Depression rates among young adults have more than doubled since 2017.

- A new study found that chronic stress reduces Reelin protein in the gut by nearly 50% in animal models.

- Reelin supports both neural plasticity and gut barrier integrity, linking the brain and digestive system biologically.

- When the gut barrier weakens, inflammatory signals rise and inflammation is increasingly associated with depression.

- The implication: depression may be a systems-level condition involving the gut-brain axis, not just neurotransmitters

The problem with Prozac and the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors or SSRIs (a class of antidepressant medications) that followed it was built into the theory it was based on. The entire drug class rests on the serotonin hypothesis: the idea that depression is caused by low serotonin in the brain, and that blocking its reabsorption would restore mood. It was a clean, elegant model. It was also, at best, incomplete.

For many patients, SSRIs simply don't work. The landmark STAR*D trial, the largest real-world antidepressant study ever conducted, found that only 37% of patients achieved full remission on their first medication. Many cycled through two, three, four different drugs and never got there. For those who do respond, the relief often takes 4 to 12 brutal weeks to arrive, during which the person is still suffering, still at risk, still waiting. And even when SSRIs do help, they carry a familiar roster of side effects such sexual dysfunction, emotional blunting, weight gain and a strange initial spike in anxiety that can make the first weeks of treatment feel worse than the illness itself.

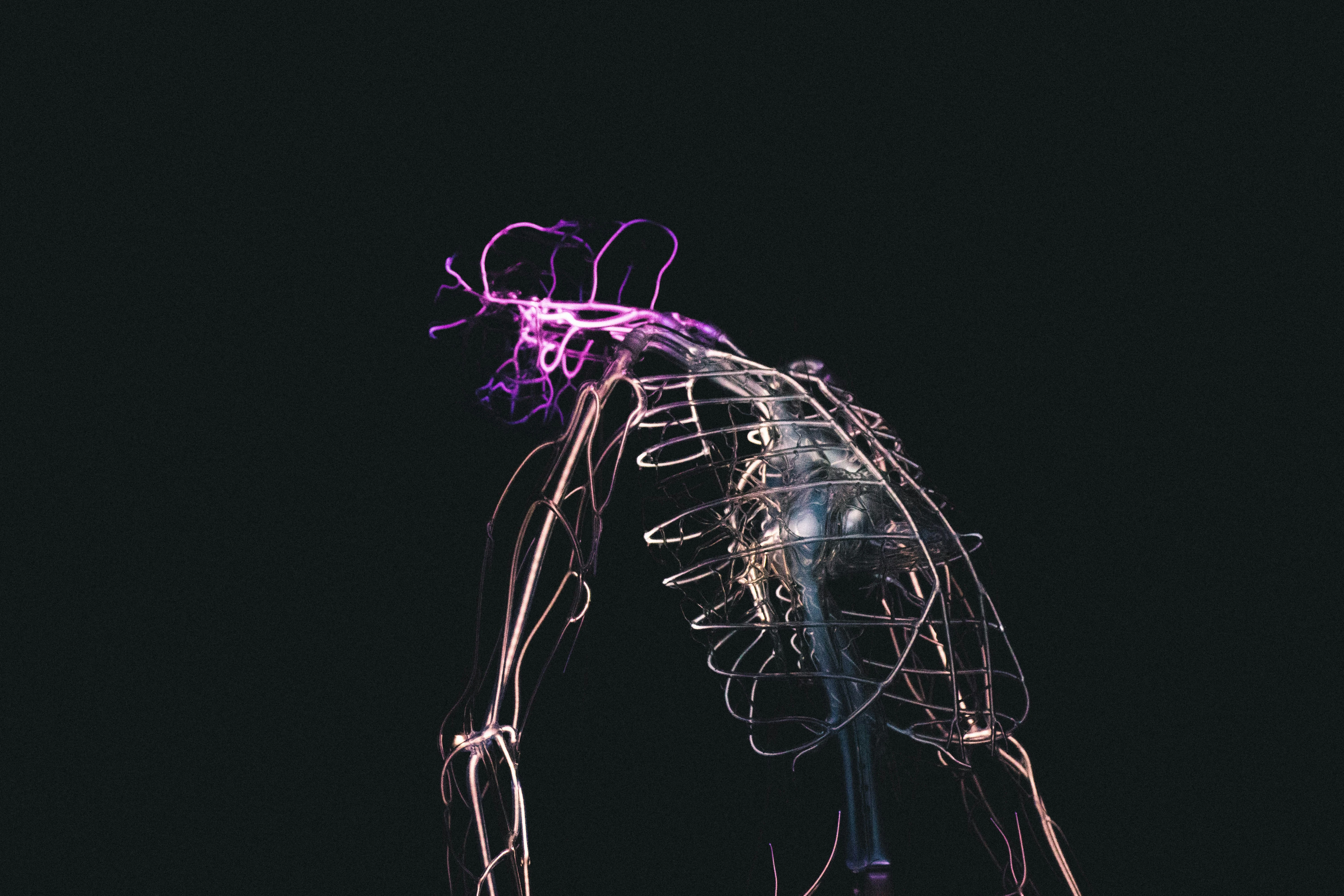

The deeper problem is what SSRIs ignore. They target one neurotransmitter, in one organ, through one mechanism. But emerging research increasingly suggests that depression is not a single-organ problem. It is a whole-body disorder and the organ we've been neglecting most may be the one sitting right below the stomach.

Today, 47.8 million Americans, nearly 1 in 5 adults, live with depression, the highest rate ever recorded. Rates among young adults have more than doubled since 2017.

Now, a small research team at the University of Victoria may have found the reason why and the answer is not what anyone expected. According to their new study, published in the journal Chronic Stress, the missing piece may be your gut. Specifically, it may be a protein called Reelin one that we've been overlooking for decades, quietly doing a job that no one knew it had.

What they found suggests a fundamentally different way of understanding depression.

A Brief History of Getting Depression Wrong

To see why this discovery matters, it helps to look at how depression treatment has evolved and why those approaches keep falling short.

The first pharmaceutical treatments for depression were stumbled upon almost entirely by accident. In the 1950s, chemists experimenting with compounds derived from World War II-era rocket fuel discovered that two drugs, iproniazid and isoniazid, originally tested as tuberculosis treatments, had unexpectedly powerful effects on patients' moods. They boosted levels of monoamine neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, and the modern era of antidepressant pharmacology was born.

The first generation of antidepressants tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), were a genuine breakthrough. For the first time, a pharmacological treatment existed for major depression. But they came with serious problems: dangerously narrow therapeutic windows, severe interactions with common foods, and side effects ranging from dry mouth and constipation to fatal cardiac toxicity in overdose.

The next revolution came in 1987, when the FDA approved fluoxetine, known commercially as Prozac, the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Within a year, nearly 2.5 million prescriptions had been dispensed. SSRIs became a cultural phenomenon, credited with making antidepressants accessible to millions who couldn't tolerate the older drugs. The number of visits to general practitioners for depression surged from 10.9 million in 1988 to 20.4 million in 1994, and antidepressant prescriptions tripled from 40 million to 120 million in the same period.

But the Prozac revolution had a ceiling. As researchers from Oxford University noted in a 2024 review published in Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, SSRIs carry significant problems including anxiety on treatment initiation, delayed onset of therapeutic effect, sexual dysfunction, and overall modest efficacy. More damningly, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, the largest real-world antidepressant trial ever conducted, found that only 37% of patients achieved full remission on their first antidepressant, and even when patients cycle through multiple medications, a significant proportion never achieve full remission at all.

Perhaps most troubling is the timeline. Even when SSRIs work, they take 4–12 weeks to produce meaningful relief. For someone in the grip of severe depression, that is 4–12 weeks of suffering while waiting for a drug that may not even work. It's a treatment reality that has driven renewed urgency in psychiatric research, from ketamine-based therapies to psychedelics and now, to the gut.

The Forgotten Organ: Your Gut's Secret Role in Mental Health

Here is something that doesn't appear in most depression pamphlets: approximately 95% of the body's serotonin, the same neurotransmitter that SSRIs target in the brain, is produced in the gut.

Your intestines contain more than 100 million nerve cells, forming what scientists call the enteric nervous system (ENS), a web so complex and autonomous that it's often nicknamed "the second brain."

This is not a metaphor. The ENS communicates directly with the central nervous system through multiple pathways, most notably via the vagus nerve, a sprawling highway of nerve fibers that runs from the brainstem all the way to the abdomen. Approximately 80–90% of the signals traveling along the vagus nerve flow upward, from gut to brain, meaning your intestines are sending far more information to your brain than the other way around.

The scientific field studying this relationship is known as the microbiome-gut-brain axis (MGBA). Research output in this area has exploded, a comprehensive bibliometric analysis identified 980 relevant publications on the MGBA-depression connection, with a dramatic increase in research since 2014. What those studies collectively show is striking: individuals with depression consistently display altered gut microbiome profiles compared to healthy controls, with reduced levels of beneficial bacterial species like Faecalibacterium and Coprococcus and increased levels of potentially inflammatory bacteria.

The relationship is bidirectional. Stress alters the gut microbiome. An altered gut microbiome worsens stress and inflammation. That inflammation crosses back into the brain, where it drives depressive symptoms. Depression has increased by 60% in the U.S. population from 2013–2014 to 2021–2023; a trajectory that runs parallel to rising rates of inflammatory disease, dietary change, and gut dysbiosis.

Yet despite all this evidence, mainstream psychiatry has been slow to connect the dots. We've continued designing treatments for the brain while the gut quietly deteriorates.

Enter Reelin: The Protein That Links Everything

This is where the University of Victoria’s new research becomes especially important.

Published in the journal Chronic Stress, the study focuses on a protein called Reelin, a large extracellular matrix protein that has been studied for decades in the context of brain function. Scientists had already established that people diagnosed with major depressive disorder have significantly lower levels of Reelin in their brains, as do rodents exposed to chronic stress. Previous research had even demonstrated that Reelin injections could produce antidepressant-like effects in animal models. But no one had looked closely at what Reelin was doing in the gut.

What Dr. Hector Caruncho's team at UVic found was remarkable. Reelin is present throughout the gut lining, where it appears to play a critical structural role: regulating the turnover of intestinal epithelial cells. Here's why that matters. The entire lining of the intestine must be replaced every three to five days. This rapid renewal is essential because gut lining cells are constantly exposed to potentially damaging substances in the digestive tract. Reelin helps promote the migration of new cells up the villi, the finger-like projections that line the intestine, to replace the old ones.

When Reelin levels drop, this renewal process falters. The gut barrier weakens. Bacteria, toxins, and other molecules that should stay inside the intestinal tract begin leaking into the bloodstream. A condition commonly called "leaky gut." The immune system responds to these invaders with inflammation. And that inflammation doesn't stay confined to the abdomen. It travels through the bloodstream and crosses into the brain, where it worsens depression.

"The gut-brain axis is becoming essential to understanding many psychiatric disorders, including depression" says Dr. Hector Caruncho, Professor and Canada Research Chair in Translational Neuroscience

What the study found was that chronic stress reduces Reelin levels by approximately 50% and diminishes specific Reelin-immunoreactive cells by around 55% in the small intestine's lining. In a single experiment, the team had identified a molecular mechanism that could link chronic stress, gut damage, and worsening depression into one connected biological story.

The Experiment and Its Stunning Results

To test their hypothesis, the UVic team exposed 32 Long-Evans rats to 21 days of chronic stress via corticosterone injections, a well-validated method for inducing depressive-like behavior in rodents. After establishing the stress-depression model, the researchers administered either a placebo or a single injection of 3 micrograms of recombinant Reelin protein.

The results were striking on multiple fronts. The Reelin injection normalized protein levels in the intestines and appeared to restore the cellular architecture of the gut lining itself, reversing the damage caused by chronic stress at a structural level. At the same time, the rats that had previously exhibited depressive-like behaviors, including increased immobility in the forced swim test, showed a reversal of those symptoms.

In animal models, a single injection restored gut integrity and produced measurable antidepressant-like effects.

"Taken together, these results may have important implications for the management of major depressive disorder," says Ciara Halvorson, a neuroscience PhD student at UVic and the study's first author. "This is especially true for people who live with both depression and gastrointestinal conditions."

That dual relevance is significant. An estimated 30–50% of people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) also suffer from depression or anxiety, and the comorbidity has long frustrated clinicians who had no single biological framework to explain it. Reelin may provide exactly that framework.

Why University of Victoria's Study Is Different From Everything Else

What makes Reelin compelling and different from the countless other "promising discoveries" that never make it out of the lab, is its dual-action mechanism.

Current antidepressants target brain chemistry. Ketamine, one of the newest approved treatments, works on glutamate receptors in the brain. Even the most innovative interventions remain brain-focused. Reelin is different. It operates simultaneously in the gut and the brain, addressing two of the core biological pathways implicated in depression at once: gut barrier integrity and neural function.

In the brain, Reelin plays essential roles in neural development, synaptic plasticity, and the maintenance of healthy neural circuits. Lower Reelin has been consistently observed in the brains of people with depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

In the gut, Reelin maintains the structural integrity of the intestinal lining. Restoring it potentially repairs the entire gut-brain circuit that chronic stress has broken.

"If Reelin protects against leaky gut by supporting the renewal of the gut lining," Halvorson explains, "Reelin may thereby protect against the worsening of depression symptoms triggered by inflammatory immune responses to leaked gut material."

This mechanism also helps explain one of the great mysteries of modern psychiatry: why do so many patients with depression also have gastrointestinal complaints? Why does gut disease so often accompany mental illness? An estimated 30–50% of people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) also suffer from depression or anxiety.

What This Means for the Millions Living With Depression

For the 47.8 million Americans currently struggling with depression, especially the 35.1% of low-income Americans whose rates are nearly triple the national average. the implications of this research offer cautious but genuine hope.

The Reelin discovery is part of a broader, rapidly evolving scientific consensus: depression is not just a brain disease. It is a whole-body disorder in which the gut, the immune system, and the brain are all deeply implicated. The future of depression treatment will almost certainly be more holistic, targeting the biological systems that connect these organs rather than any single neurotransmitter in isolation.

In the meantime, the emerging science does point to some actionable insights. Gut health matters for mental health. Chronic stress is measurably damaging to the intestinal lining. Anti-inflammatory dietary patterns, probiotic interventions, and stress reduction are not alternative remedies, they are legitimate targets along the very biological pathways that the Reelin research has now illuminated.

The next time someone tells you to trust your gut, they are being more scientifically accurate than they know. Your mental health may literally start in your stomach. And for the first time, we have a molecular protein to help explain exactly why.

A Note From Sparklin: Why We Are Writing About Brain Science

At first glance, this might seem like an unusual place to find an article about gut proteins and antidepressants.

Sparklin is a design innovation company, we design products, shape interactions, and help businesses build things people actually want to use. But great design has never really been about screens and buttons. It's about people: how they feel, how they function, how they move through the world. Depression affects nearly 1 in 5 of the adults using every product we help build. It shapes attention spans, decision-making, motivation, and behavior in ways no amount of A/B testing will ever fully capture. When science fundamentally reframes what depression is, not a brain malfunction but a whole-body systems failure, that changes how we think about the humans on the other side of every interface.

Sparklin tracks research like this because the future of innovation is not siloed. We work increasingly in healthcare and wellness spaces where the design stakes are high and the users are complex and where understanding the biology behind behavior is not optional. The most interesting breakthroughs of the next decade will happen at intersections: between science and technology, between what medicine discovers and what products can do with it. We intend to be at those intersections.

The best experiences are built by people who never stop being curious about what it means to be human.

Note: This research around Reelin and how it affects depression is still in its early stages. The UVic study was conducted in animal models, meaning the role of a single protein observed in rats cannot be directly applied to the complexity of human depression. Extensive work such as dosing, safety evaluation, delivery methods, and human clinical trials will be required before any Reelin-based therapy can be considered for clinical use, a process that typically takes decades. The study was funded by CIHR and NSERC and is being advanced by the Caruncho Lab. However, the broader scientific direction is credible, especially as growing evidence shows that depression cannot be explained solely by the monoamine hypothesis and instead involves changes in brain structure, neurotransmitter systems, and neural connectivity, making integrated gut-brain approaches increasingly relevant.