This essay explains why flexible schedules work well for some kinds of work and fail for others. By examining interruption cost, stopping cost, and how value appears over time, it offers a structural way to design schedules, teams, and expectations that match how work actually produces results.

The Flexibility Illusion in Modern Work

Flexible work is widely treated as an unqualified good in modern careers.

Flexibility refers to the ability to vary when, where, and how work is done without reducing output quality or momentum.

People start at different hours. Some work remotely. Others take breaks during the day and return later. In many professions, this has improved autonomy, access, and sustainability. It has also expanded who can participate in certain kinds of work.

Discussions of flexibility often assume that time behaves the same way in every profession. That assumption fails because progress behaves differently in different types of work.

We often talk about work as if time and value have a universal relationship. Under that view, flexibility merely redistributes effort. The work still resolves in roughly the same way, just on a different schedule.

The assumption, that time and value relate uniformly, shapes how schedules are designed, how productivity is measured, and how performance is evaluated.

It also underlies many debates about remote work, hybrid policies, async work, and flexible schedules in modern organisations.

In the United States and the UK, this assumption often focuses on remote work and knowledge productivity. In Germany, it is framed around working hours, predictability, and coordination. In Singapore, it tends to surface as questions about long hours and the sustainability of high-intensity roles.

Different kinds of work respond to time in different ways. The relationship between time and value varies sharply across tasks.

Some roles produce progress that remains visible outside the individual doing the work. Tasks can pause and resume. Handoffs are expected and reliable. Flexible schedules align with how the work produces results.

Other roles concentrate progress inside the person doing the work.

Here, “inside the person” does not refer to emotion, intuition, or personal motivation. It refers to judgment, prioritisation, relative importance, and partially evaluated options that exist only while attention is continuous. This state can be influenced by notes, but it cannot be fully externalised.

Context builds through continuity. Decisions depend on sequences that cannot be fully reconstructed once broken. Interruptions change not just the pace of the work, but its direction.

The difference has little to do with discipline or commitment. It lies in whether work survives fragmentation or degrades under it.

We usually explain these differences with cultural language. Hustle culture. Toxic environments. Work–life balance. Each label points to something real, but none explains why the same schedule feels sustainable in one role and exhausting in another.

When flexibility is discussed without accounting for how work actually behaves, disagreements about hours begin to feel personal. They sound like arguments about motivation, values, or balance. More often, they are arguments about structure wearing the clothes of values.

Most debates about modern work are not really about freedom or discipline. They are failures of fit.

We keep designing schedules around the mythology of work, how we believe productive work should look, rather than around the behavior of work, how progress actually survives.

Work has a shape. Schedules that ignore the shape create continuity debt.

Understanding this does not require rejecting flexibility. It requires treating time as more than a neutral container for effort. In many professions, time actively shapes how value gets produced.

In these conversations, time is treated as a moral signal. Longer hours imply seriousness. Shorter hours imply restraint. This essay treats time as a mechanical variable, not a moral one. In many kinds of work, time changes the behaviour of the work, not just how much effort you put in.

This misunderstanding is what I’ll call the flexibility illusion: the belief that changing when and where work happens affects all work in the same way.

In practice, the disagreement hides a cost. When work is interrupted or forced to stop too early, progress does not carry forward. Time gets spent, but less of the work remains usable.

I’ll call this cost continuity debt.

Continuity debt is the accumulated cost of running work in conditions that prevent progress from persisting. It grows each time work restarts instead of picking up where it left off.

Until that distinction is clear, conversations about modern work will continue to talk past the mechanics that actually matter.

TL;DR

- Flexibility works only when work can survive interruption.

- Some work carries its state in systems; other work carries it in people.

- Good work design prioritises fit over flexibility, matching schedules to how work actually preserves and produces value.

- When work keeps restarting, exhaustion follows even at normal hours.

- Interruption cost and stopping cost explain why schedules feel unfair.

- Continuity debt is the hidden cost of work that keeps restarting instead of carrying forward.

Flexibility is not imaginary. It is real, meaningful, and valuable where it exists.

Some types of work allow you to pause mid-task and resume later with little or no loss. You can leave early, join late, take a weekday off, or shift effort across days and still produce the same outcome. Missed time can be recovered. Progress survives.

This is not true everywhere.

Many kinds of work do not allow you to step away midstream without consequence. Pausing resets context. Leaving early delays resolution. Time cannot simply be “made up” later because the work itself changes when attention breaks.

Flexibility, in this sense, is not a universal right of modern work. It is a structural privilege that emerges when the work can survive interruption.

Where flexibility exists, it should be valued and protected. Flexibility remains viable only while interruption does not change the work itself. Once the work begins to reset, the flexibility disappears.

Wanting flexibility is natural. Problems arise when flexibility is assumed to apply evenly, and people or roles are judged when it does not.

This essay argues that flexibility is not a moral preference or lifestyle benefit, but an outcome of how work behaves under interruption and over time.

Attention Fragility: Why Some Work Breaks When Focus Breaks

Most career advice focuses on skills, interests, and outcomes. It asks what you are good at, what you enjoy, and what offers growth or financial upside. It rarely asks what the work requires while it is being done.

A more revealing question sits beneath many career frustrations:

What happens when focus breaks mid-work?

Some work absorbs interruption with little cost. Attention can drift briefly, conversations can pause, and progress resumes without friction because most of what matters already exists outside the person doing the work. Notes, checklists, logs, and routines carry the state of the work forward.

In this kind of work, context accumulates through sustained attention. Decisions are shaped by sequences that build over time. Some of that context can be written down, but much of it cannot be reconstructed once lost.

When attention breaks, progress does not resume from the same point. You return knowing something mattered, but not remembering what made it matter. The work must be rebuilt before it can move forward again.

This is attention fragility: work that only makes progress when attention stays intact.

Each interruption increases the effort required to re-enter the work, the hidden cost often described as context switching. Returning means reconstructing priorities, constraints, and half-made decisions before meaningful progress can continue.

Even careful notes rarely capture where the work was heading, which options had already been ruled out, or why one direction felt more promising than another.

This difference is easy to observe.

A pilot can recover from brief interruptions because procedures preserve state. A delivery rider can pause and resume because the app holds the state of the work.

A surgeon cannot treat attention the same way once a procedure is underway. A filmmaker in an edit room cannot outsource judgment mid-scene. A researcher following a fragile line of reasoning returns slightly misaligned with the problem.

These differences have little to do with seriousness or professionalism in the person doing the work. They depend on how much of the work’s state exists internally while it is being done.

Career advice often frames interruption as a personal failure. The focus falls on habits, discipline, or boundaries. In practice, interruption behaves more like a structural variable.

Some work tolerates fragmentation without changing its outcome. Other work shifts in quality and direction each time attention breaks.

In one case, interruption delays completion. In the other, it alters direction and quality.

Strain gets attributed to motivation when the issue is interruption cost. Burnout gets attributed to effort when the issue is fragmentation.

Many people are exhausted not by effort, but by repeatedly reconstructing unfinished work. Exhaustion often accumulates even at normal working hours because continuity debt builds. Progress keeps restarting instead of carrying forward.

This leads to a second question, just as important as the first:

Even if attention holds, does the work benefit from fixed time, or does it need flexibility to reach a meaningful end?

When Fixed Schedules Help Work and When They Hurt Work

Stopping at the end of the day does not always stop work cleanly. Sometimes it resets it.

Stopping cost is the loss created when work is forced to stop before it has reached an internal point of resolution.

When attention can remain continuous, a different question becomes relevant: does the work benefit from fixed hours, or does it need flexibility to arrive at a meaningful stopping point?

Fixed work schedules shape work in different ways depending on how progress is made.

In some roles, defined start and end times simplify coordination. Work can be handed off without loss. Decisions remain local to the task at hand. Shared hours reduce the need to renegotiate context.

This is why roles such as operations, customer support, transportation, and on-call services often function more predictably within clearly defined hours. Work moves through visible stages. Stopping points are easy to identify. Ending work does not meaningfully change what comes next.

Some work only moves forward after it reaches a natural stopping point.

Advancement does not move through clear stages. It builds toward internal resolution points that appear only after sustained engagement. Ending work because the clock has run out often leaves the work unfinished in a way that makes returning slower and less certain.

Anyone who has paused mid-design, mid-edit, or mid-analysis recognises this pattern. You return knowing the work was close, but not complete. Time is spent reorienting, rebuilding context, and retracing decisions that had already been made.

This is when people say things like, “I need a moment to get back into this,” or “I was almost there,” or “Let me reorient before I change anything.” These statements describe the cost of restarting work that had not yet reached a natural stopping point.

None of this suggests that work should sprawl endlessly or ignore limits. Boundaries still matter. The question is where they are placed.

Fixed time can either preserve momentum or repeatedly reset it. Each reset increases the effort required to regain orientation before useful work can continue.

Film editing makes this tension easily visible. Production schedules are fixed. Rooms are booked. People are coordinated weeks in advance. Yet the work inside an edit does not resolve on a clock. Scenes settle only after sustained attention. Ending a session early protects the calendar, but often delays the cut itself.

Courtrooms show a similar pattern under different constraints. Proceedings run on strict schedules, but the thinking that shapes a case does not. Arguments develop through continuity. When time runs out, the judge may pause the session. For everyone else, that pause often stretches the work rather than containing it.

Product launches expose the same structure in modern organisations. Dates are locked. Teams align across functions. Some tasks benefit from strict hours. Others move forward only when problems are held long enough to resolve. Treating all stages as interchangeable usually slows the parts that matter most.

Even at large production scales, the pattern holds. Film sets coordinate hundreds of people on fixed schedules, while critical creative decisions resist neat time boundaries. Progress comes from managing the tension between these forces, not choosing one schedule philosophy over the other.

The distinction lies in what happens when work is interrupted versus when it is ended by the clock.

In some roles, stopping changes little about what follows. In others, stopping shifts the work backward or sideways before it can move forward again. Together, these differences explain much of the tension people experience with modern schedules, without relying on motivation, values, or personal discipline.

Continuity Debt: The Hidden Mechanics of Time in Different Kinds of Work

Key Definitions

- Interruption cost: the effort required to reconstruct context after attention breaks.

- Stopping cost: the loss created when work is forced to stop before reaching internal resolution.

- Flow work: work whose state lives primarily in a person’s accumulated judgment.

- Stack work: work whose state persists in systems outside any single person.

Two people can work the same hours and still experience completely different workdays. Most friction around schedules comes from two mechanics that are rarely named.

Interruption cost is the effort required to resume work after attention breaks.

Stopping cost is the effort required to resume work after it is forced to stop before reaching an internal point of resolution.

These costs vary by task, not by profession. They explain why similar schedules, habits, and expectations produce very different outcomes even across roles that look similar from the outside.

Once these costs are visible, flexibility stops being a lifestyle preference and starts looking like an engineering decision. This is why debates about productivity tools, remote work, or work–life balance rarely resolve. They debate preferences and policies while the constraints are determined by how the work itself behaves.

Schedules succeed or fail based on fit, not intention.

This framework is useful for designing work schedules, remote policies, team structures, and personal work habits that match how work actually produces value.

Two further distinctions explain how those costs behave.

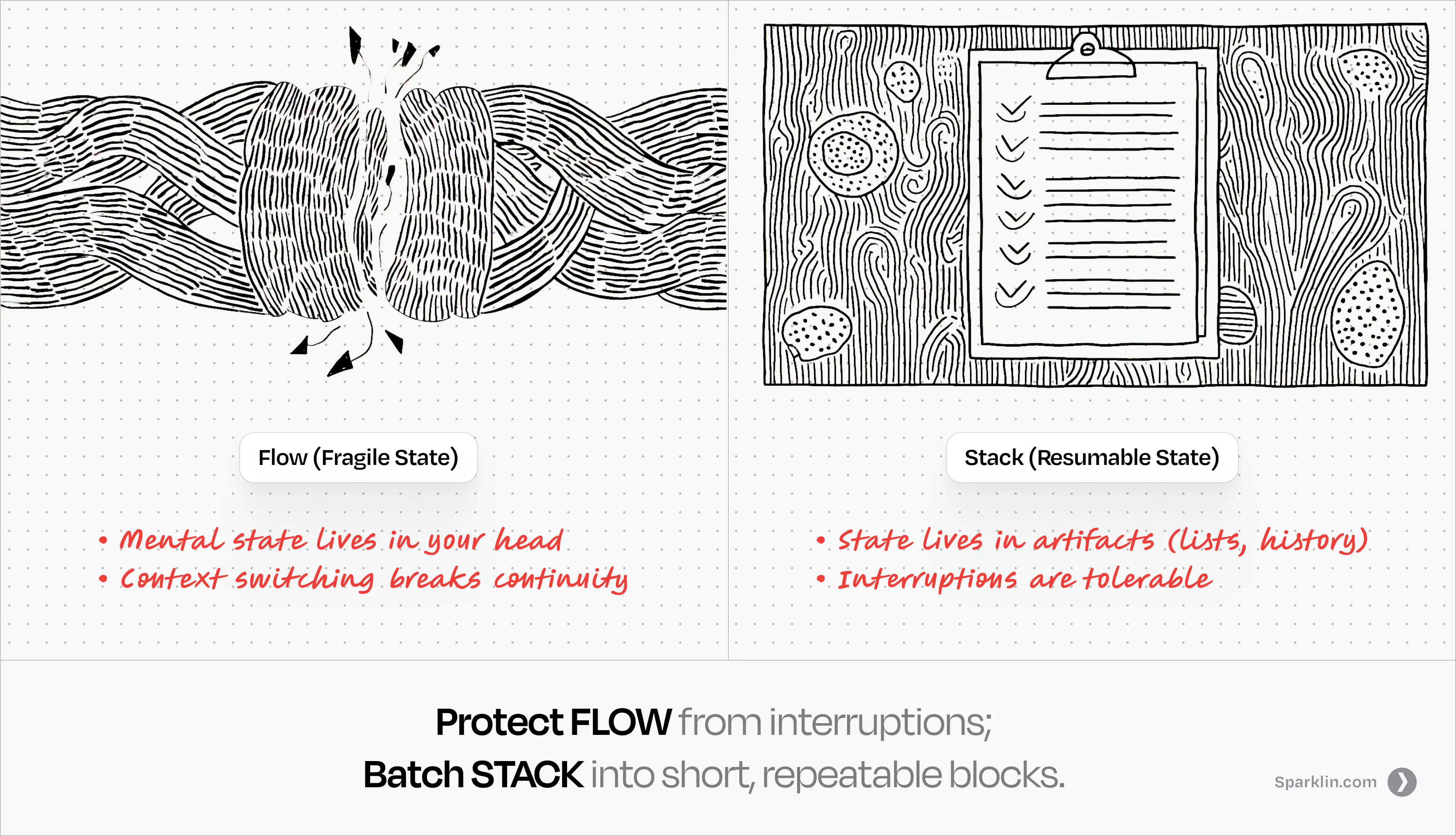

Flow and Stack describe how work survives interruption.

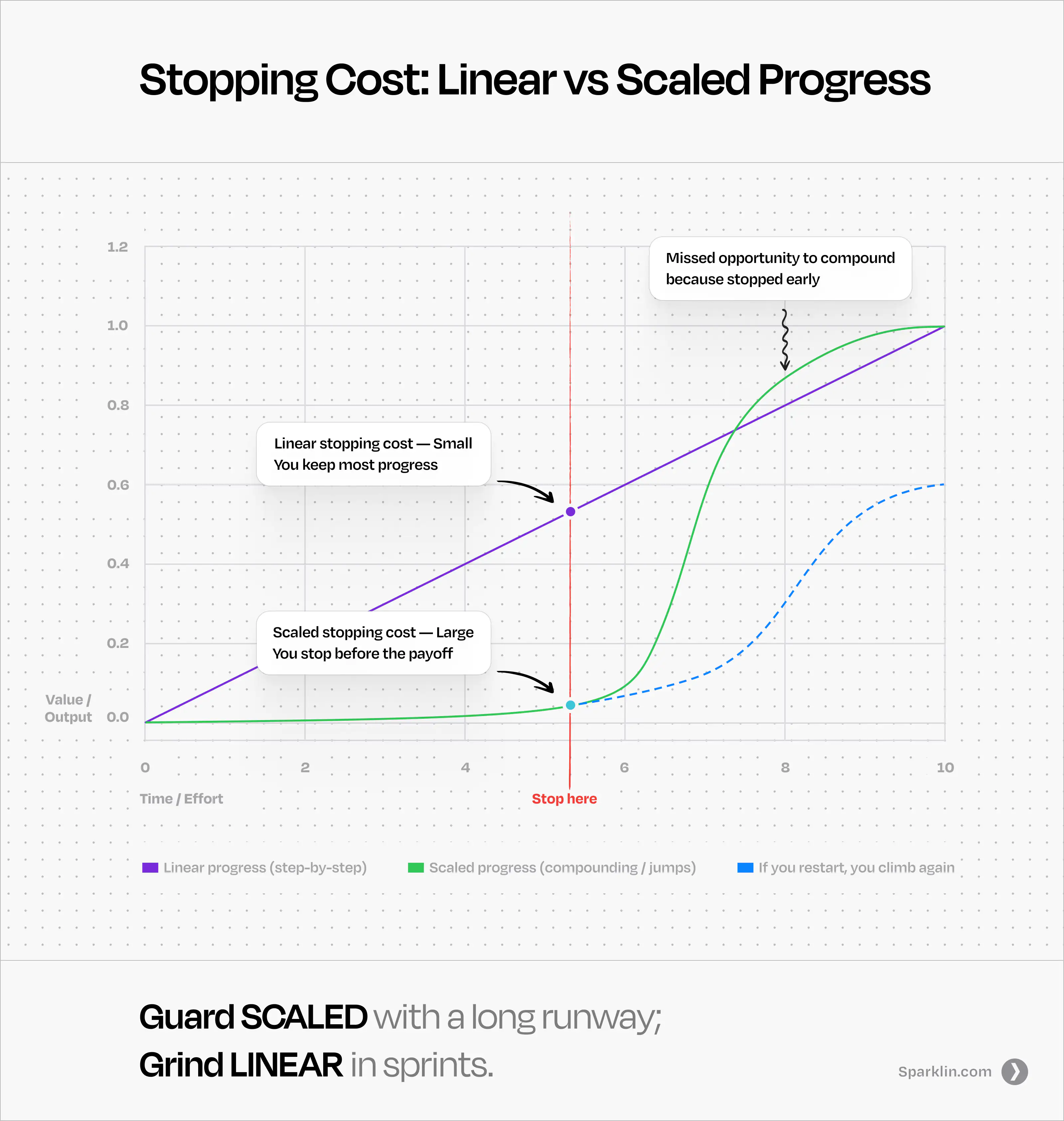

Linear and Scaled describe how value appears over time.

Together, they explain why similar schedules produce different outcomes across kinds of work, and why time amplifies progress in some work but erodes it in others.

How Work Handles Attention: Flow and Stack

The key question is whether work can survive interruption without rebuilding judgment.

Some work carries its state externally.

When progress lives in tickets, documents, checklists, logs, or systems that persist outside any one person, I call it Stack work. Another person can step in without needing a detailed explanation. When attention breaks, the work resumes from roughly the same place.

You see it in operational tasks like customer support, transportation, compliance, ticket-driven engineering, and many service roles. Interruption changes throughput, but it does not change the structure of the work.

Other work carries its state internally.

When progress depends on accumulated context, judgment, and relative importance that live inside the person doing the work, I call it Flow work. After attention breaks, the work does not resume from the same place. You come back and spend time rebuilding context before you can make good decisions again.

You see it in tasks like research, design exploration, editing, strategy, writing, diagnosis, and complex problem solving. A product team in Silicon Valley, a policy unit in London, a research lab in Germany, and a regional headquarters in Singapore can look nothing alike on the surface. Each runs into the same limit when work depends on context that cannot be paused and resumed without loss. Returning often begins with reorientation rather than execution.

Flow and Stack describe how work behaves under interruption. They do not describe personality, discipline, or preference.

How Value Appears Over Time: Linear and Scaled

Some work converts time into output predictably.

Two more hours usually produce two more finished units. When progress accumulates visibly and proportionally, I call it Linear work. Stopping early delays completion, but does not fundamentally change the outcome.

You see it in execution-heavy project phases, operations, maintenance, support queues, production tasks, and delivery-oriented roles.

Other work behaves differently.

Time buys you a chance at a step change. Hours may pass with little visible movement until something resolves and progress becomes legible. When work often reaches value late in the session, I call it Scaled work.

Claude Shannon spent years at Bell Labs on a problem that offered almost nothing to show along the way. He wanted a way to treat information as a measurable quantity.

Most days produced fragments: thought experiments, discarded paths, notebooks full of symbols that meant little to anyone else.

Then the work concentrated into a single paper that reshaped communication, computation, and signal processing.

This is how Scaled Flow work behaves. Time funds compounding context. Value arrives in bursts, not in a steady line. End the session too early and the work stays unfinished in the only way that matters: nothing usable emerges.

Barbara McClintock’s work followed a similar arc. Her research on genetic transposition unfolded over decades, largely outside the dominant frameworks of her field. Progress remained internal for long periods, visible only through accumulated understanding.

Recognition came much later, after the structure she had uncovered became unavoidable. The work became legible only after enough context had converged.

You see this pattern in research, invention, creative direction, early-stage product work, strategy, leadership decisions, and complex problem framing.

Linear and Scaled describe the shape of outcomes over time. They do not describe ambition, importance, or effort.

Why Titles and Advice Miss This

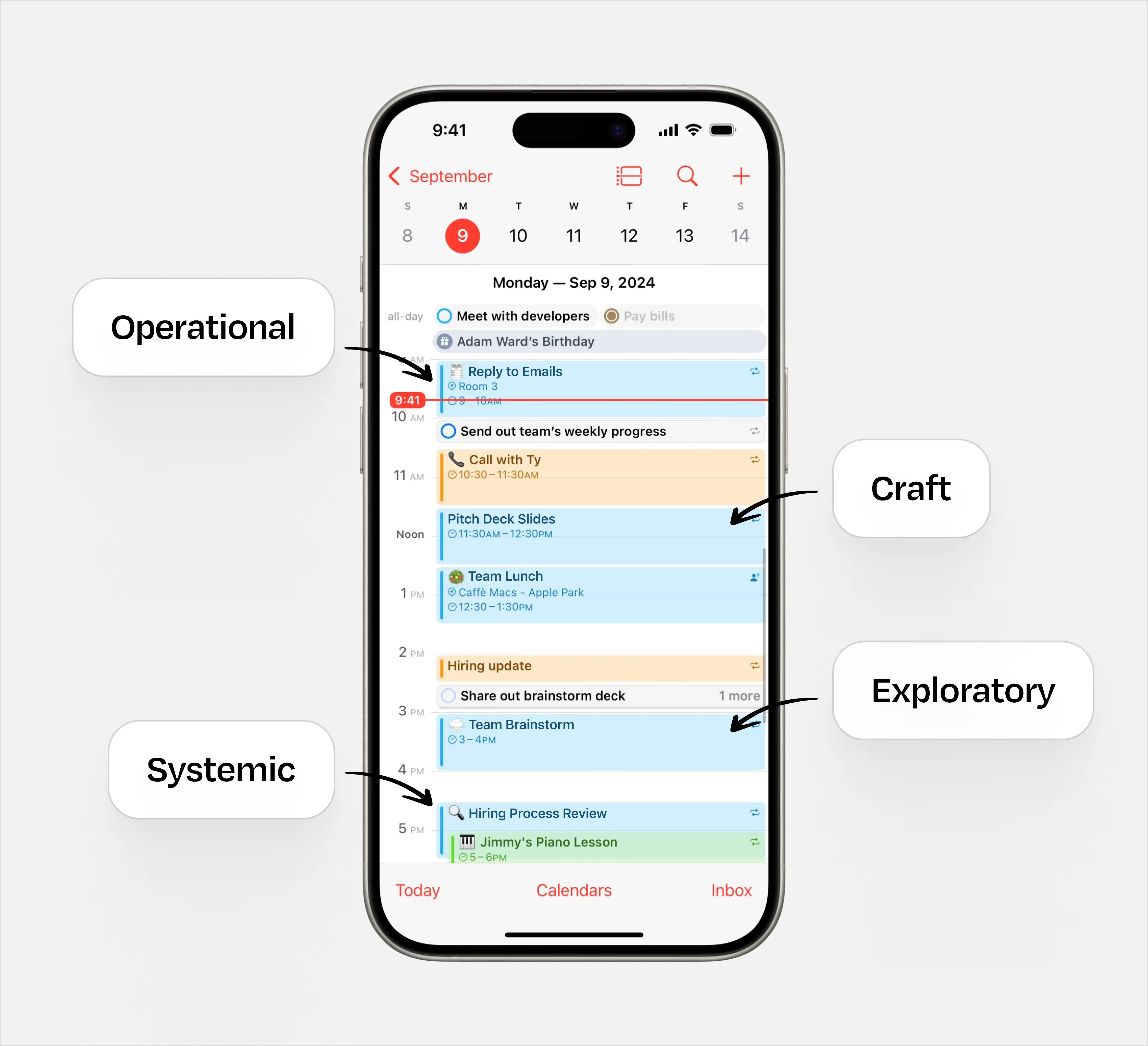

Job titles hide these differences because most roles contain multiple types of work.

A software engineer may spend mornings responding to tickets and afternoons exploring a new system design. The title stays the same, but the way the work behaves, changes.

A manager may alternate between scheduled reviews and open-ended synthesis. The calendar stays the same. The work does not.

This is why people often feel mismatched to roles they appeared to choose correctly. In many cases, the issue lies in how the work is being run rather than in the profession itself.

- Flow work loses coherence in interruption-heavy environments.

- Scaled work loses payoff when forced to stop early.

- Stack work slows when treated as immersive.

- Linear work stalls when treated as exploratory.

Much work is mis-operated rather than mis-chosen.

Interruption cost and stopping cost describe how work behaves under pressure. When combined, they produce four stable modes. Each mode rewards a different way of using time.

Friction appears when work is placed inside schedules that do not match how it produces value.

The next section lays out those patterns directly.

The Four Modes of Modern Work

When interruption cost and stopping cost are considered together, work begins to cluster into a small number of stable patterns.

These patterns are not job titles, personality types, or career stages. They describe how work behaves under interruption and over time. Each mode reflects a different way value is produced and preserved.

Much confusion around schedules, productivity, and flexibility comes from treating these modes as interchangeable. In practice, each mode rewards a different use of time and degrades under different constraints.

Most professions move between these modes. Problems arise when work is locked into a mode it does not fit. No mode is inherently better than another. Each exists because it serves a real human or societal need.

Together, these four modes describe the most common kinds of work found in modern jobs, teams, and organisations.

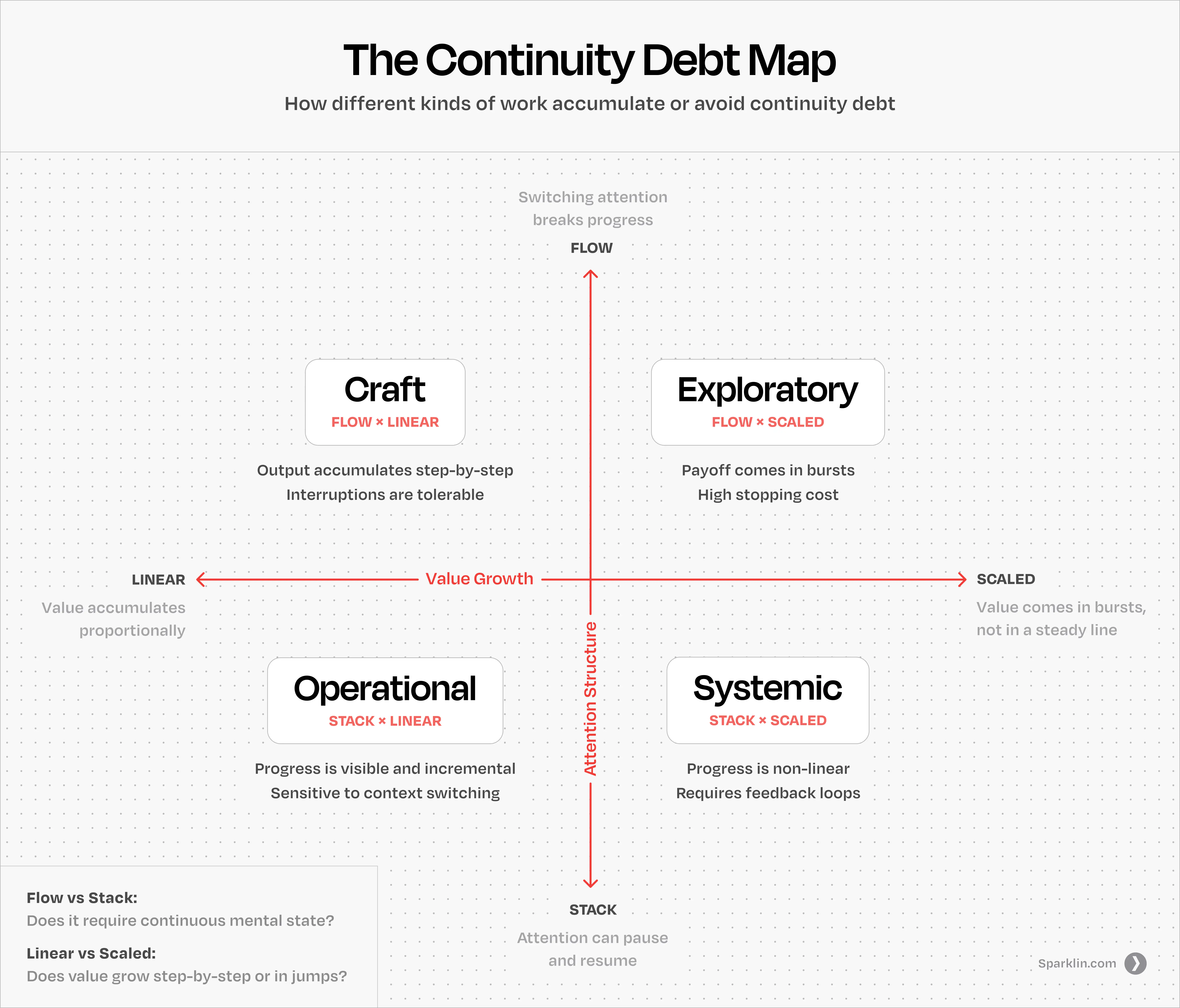

- Vertical axis: How work handles attention (Flow ↔ Stack)

- Horizontal axis: How value grows over time (Linear ↔ Scaled)

(The diagram supports the model. The mechanics live in the text.)

Operational Mode

(Stack × Linear)

Operational Mode describes work whose state survives interruption and whose output grows proportionally with time.

Tasks move through visible stages. Work can pause and resume. Progress remains legible outside the individual doing it. Handoffs are normal and expected.

Operational Mode optimises for reliability, throughput, and coordination. Judgment lives in procedures, systems, and shared state rather than in sustained individual immersion.

Air traffic control depends on work whose state persists outside any individual. Responsibility passes between controllers, shifts change, and attention moves without losing the integrity of the system.

Shared displays, protocols, and checklists carry the work forward. Interruption affects throughput, not direction.

This is Linear Stack work at scale. Progress survives handoffs. Time produces output predictably. Reliability comes from structure, not immersion.

You see Operational Mode in operations teams, customer support, transportation, logistics, administration, compliance, and many enterprise roles. Much of hospital work runs this way, especially where failure cannot be tolerated.

Operational Mode works best when hours are defined and interruptions are normal. The work succeeds because its state persists across people and time. Stopping points are clear. Progress survives handoffs, pauses, and resumption without loss.

What this mode trades away is depth of judgment in any single moment. Outcomes depend more on system integrity than on individual focus.

Problems arise when Operational work is treated as immersive or open-ended. Time spent beyond task boundaries rarely improves results and often introduces inconsistency.

Craft Mode

(Flow × Linear)

Craft Mode describes work that depends on sustained attention but still produces finite, proportional outcomes.

Progress accumulates internally through judgment. Interruption raises the cost of resuming, even though effort still leads to completion.

Jiro Ono’s work as a sushi chef operates under a narrow constraint. Each piece has a clear beginning and a clear end, yet quality depends on uninterrupted attention from preparation through completion.

A momentary break is visible directly in texture, timing, and consistency. The task still finishes, but the result reflects the interruption.

Craft Mode optimises for local quality, completion, and control within scope. It trades away scale and leverage in exchange for coherence and ownership.

You see Craft Mode in freelancing, skilled trades, scoped creative work, independent consulting, surgery, editing, illustration, carpentry, tailoring, and much early-career professional practice. Diagnosis often shifts doctors into Craft Mode, even inside operational environments.

Craft Mode works best when time can be protected from interruption within finite working hours. Judgment accumulates through continuity, yet effort still resolves into completion.

A designer refining a single client project operates in Craft Mode. The work benefits from focus, but it does not require open-ended time to become valuable.

Problems arise when Craft work is fragmented or run inside interruption-heavy schedules. Quality degrades before effort becomes visible.

Exploratory Mode

(Flow × Scaled)

Exploratory Mode describes work where judgment compounds and value appears late.

Progress does not arrive in proportion to time spent. Long stretches may show little visible movement until ideas connect, constraints resolve, or a new framing emerges. Stopping early often means stopping before anything useful appears.

Exploratory Mode optimises for synthesis, originality, discovery, and expanding insight. It trades away predictability and short-term output in exchange for depth and possibility.

You see Exploratory Mode in research, authorship, invention, early-stage product work, strategy formation, design exploration, and complex problem framing.

A researcher following a fragile line of inquiry operates in Exploratory Mode. So does an author shaping a book or a designer defining a new system.

This work resists strict schedules. It requires long, uninterrupted stretches where ideas can settle before being evaluated.

What it trades away is certainty. Time buys possibility, not guaranteed output.

Problems arise when Exploratory work is forced to stop early or measured by linear output. Stopping cost overwhelms effort, and progress stops compounding.

Systemic Mode

(Stack × Scaled)

Systemic Mode describes work that survives interruption and produces value through leverage.

The work operates across people, systems, incentives, and structures. Progress comes from coordination, alignment, and decision environments rather than immersion. Momentum lives in the system, not in any single person.

Systemic Mode optimises for reach, coordination, and influence. It trades away immediacy and direct control in exchange for scale.

You see Systemic Mode in senior management, leadership, large organisations, politics, platform companies, large-scale entrepreneurship, and institutional governance.

Systemic Mode works best when time is predictable enough to coordinate others, decisions can be delegated, and feedback loops are visible. Progress depends less on focus and more on alignment.

What it trades away is immediacy. Outcomes arrive indirectly, shaped by many interacting parts.

Problems arise when Systemic work is treated as hands-on or judged through individual output. The work loses leverage when forced into Craft or Exploratory patterns.

Large systems make these shifts visible because no single way of working holds across all phases.

The Apollo program moved through multiple modes as the work evolved. Early physics and orbital mechanics unfolded in Exploratory Mode, where insight arrived unevenly and late.

Engineering subsystems shifted into Craft Mode, with bounded problems requiring sustained attention and internal judgment.

Launch operations ran in Operational Mode, coordinated through procedures, checklists, and handoffs that preserved state across teams.

Program leadership operated in Systemic Mode, aligning institutions, budgets, and timelines rather than executing tasks directly.

The achievement emerged from matching each phase of work to the mode it required.

No Mode Is Superior

None of these modes is inherently better than another. Each exists because it serves a real human or societal need. Modern systems rely on all four.

Most tension in modern work comes from running the right work in the wrong mode.

- Craft and Exploratory work collapse under constant interruption.

- Exploratory and Systemic work suffer when forced into early stopping.

- Operational work slows when treated as immersive.

- Systemic work fails when judged by individual effort.

The issue is rarely the profession itself. It is how the work is being run.

Understanding how work behaves makes it possible to design schedules, expectations, and flexibility around how work actually produces value.

The Same Professions Operate in Different Modes

A common mistake in how work is understood is assuming that professions map cleanly to modes.

Modes describe how work behaves, not who performs it. The same profession can move between modes depending on the task, the phase of work, and the constraints around it.

This is why disagreements about schedules, careers, and role fit often persist without resolution. The discussion stays at the level of titles, while the differences sit inside the work itself.

A Profession Is Not a Mode

Much hospital work runs in Operational Mode. It depends on defined shifts and essential handoffs, with protocols and coordination preserving the state of the work across people and time.

Diagnosis often shifts into Craft Mode. Judgment accumulates internally. Interruption increases resumption cost. Quality depends on sustained attention, even though outcomes remain finite.

Research medicine and experimental treatment extend further into Exploratory Mode, where progress appears unevenly and value emerges late.

The profession remains the same. The mechanics change.

Design Is a Visible Case, Not a Special One

Design makes these shifts easy to see because the same person often moves between modes within a single week.

Early exploration often sits in Exploratory Mode, where judgment compounds, value appears late, and stopping early resets progress.

Client delivery and refinement move into Craft Mode. Output becomes finite, continuity matters, and effort converts reliably into finished work.

Reviews, asset production, and coordination run closer to Operational Mode, where shared systems matter more than immersion.

At scale, design leadership becomes Systemic Mode work. Impact comes from setting direction, shaping decision environments, and enabling others.

The profession stays the same. The mode changes.

Where Friction Comes From

Friction appears when different modes are treated as interchangeable.

- Continuity is expected where handoffs are required.

- Proportional output is expected where value emerges late.

- Flexibility is expected where the work needs long, uninterrupted time to move forward.

- Structure is applied where exploration is still forming.

The result is misalignment, not underperformance.

This also explains why people often feel tension inside roles they otherwise enjoy. The discomfort is real, but it usually reflects how the work is being run rather than what the profession demands.

Identifying the Mode of Work

Once you can name the mode, many tensions become easier to explain.

A footballer trains in Craft Mode, competes in Operational Mode, and contributes to strategy in Systemic Mode.

A politician appears publicly in Operational Mode, develops policy in Exploratory Mode, and governs through Systemic Mode.

A cab driver operates largely in Operational Mode, while fleet optimisation or routing systems shift into Systemic Mode.

The same profession. Different mechanics.

Seen this way, the useful question is no longer “What do you do?”

It becomes “What mode is this work in right now?”

That shift resolves much of the friction people experience in modern work.

Every Kind of Work Has a Shape and a Tradeoff

Every kind of work settles into a shape.

That shape emerges from constraints: how attention behaves, how decisions accumulate, how coordination happens, and how value appears over time. Schedules, expectations, and rituals repeat across very different kinds of work because the same forces keep asserting themselves.

Some work rewards continuity. Some rewards handoff. Some compounds through judgment held in one place. Some compounds through systems that survive people.

When work is run in conditions that match its shape, progress carries forward with less friction. When it isn’t, progress restarts more often than it advances.

This is why a day can feel full yet unproductive. Attention is spent, decisions are made, and effort is real, but little carries forward. The work revisits ground it already covered because it is being run in conditions that reset it faster than it can advance.

Ignoring that shape often feels fine at first.

Early momentum compensates. Energy smooths over mismatch. Flexibility looks harmless because outcomes still arrive. Many operating styles appear interchangeable when the work is small, the stakes are contained, and judgment has not yet begun to compound.

The costs are delayed, not avoided.

Quality plateaus. Decisions take longer to settle. Work begins to revisit ground it already covered. Effort increases without a corresponding increase in outcome, because the work is being run in conditions it resists.

That is usually when explanations turn personal.

People blame focus, discipline, or talent. Teams change tools, habits, and incentives. Activity increases, but the underlying mechanics stay the same, and the friction returns in a slightly different form.

Understanding the shape does not force a choice.

It does not require moving toward scale or leverage. It does not demand fixed work schedules or unlimited flexibility. It does not prescribe a career path or rank one mode above another.

It makes the constraints visible.

Some work optimizes for calm and completion. Some optimizes for discovery and compounding. Some protects reliability. Some trades certainty for reach. Each pattern offers real benefits, and each extracts real costs.

Seeing the shape does not tell you what to choose.

It lets you design work around how it actually behaves.

Most debates about modern work are arguments about freedom. Few ask whether the work fits the way time, attention, and value actually behave. Fit determines whether time compounds or is spent recovering lost progress.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is flexibility always good?

Flexibility is beneficial only when work can pause without losing progress. When interruption resets context, flexibility increases hidden costs.

Why does creative or thinking work feel exhausting even at normal hours?

Because progress often restarts after interruption. Exhaustion comes from reconstruction, not effort.

Which types of work work best with async schedules?

Work whose state lives in systems rather than people: operational, queue-based, or well-specified tasks.

How should teams design schedules when roles mix different kinds of work?

By identifying which mode dominates at each phase and adjusting overlap, protection, and flexibility accordingly.

Is this about personality or preference?

No. These differences come from how work behaves, not from individual traits.