Who knew that chocolate and furniture could overhaul the world of photography as it once was?

This might sound like the blurb of a Lifetime documentary. In the 1970s, a seemingly trivial issue with how chocolate and furniture appeared in photographs led to a monumental change in the way Kodak—and the world—saw color.

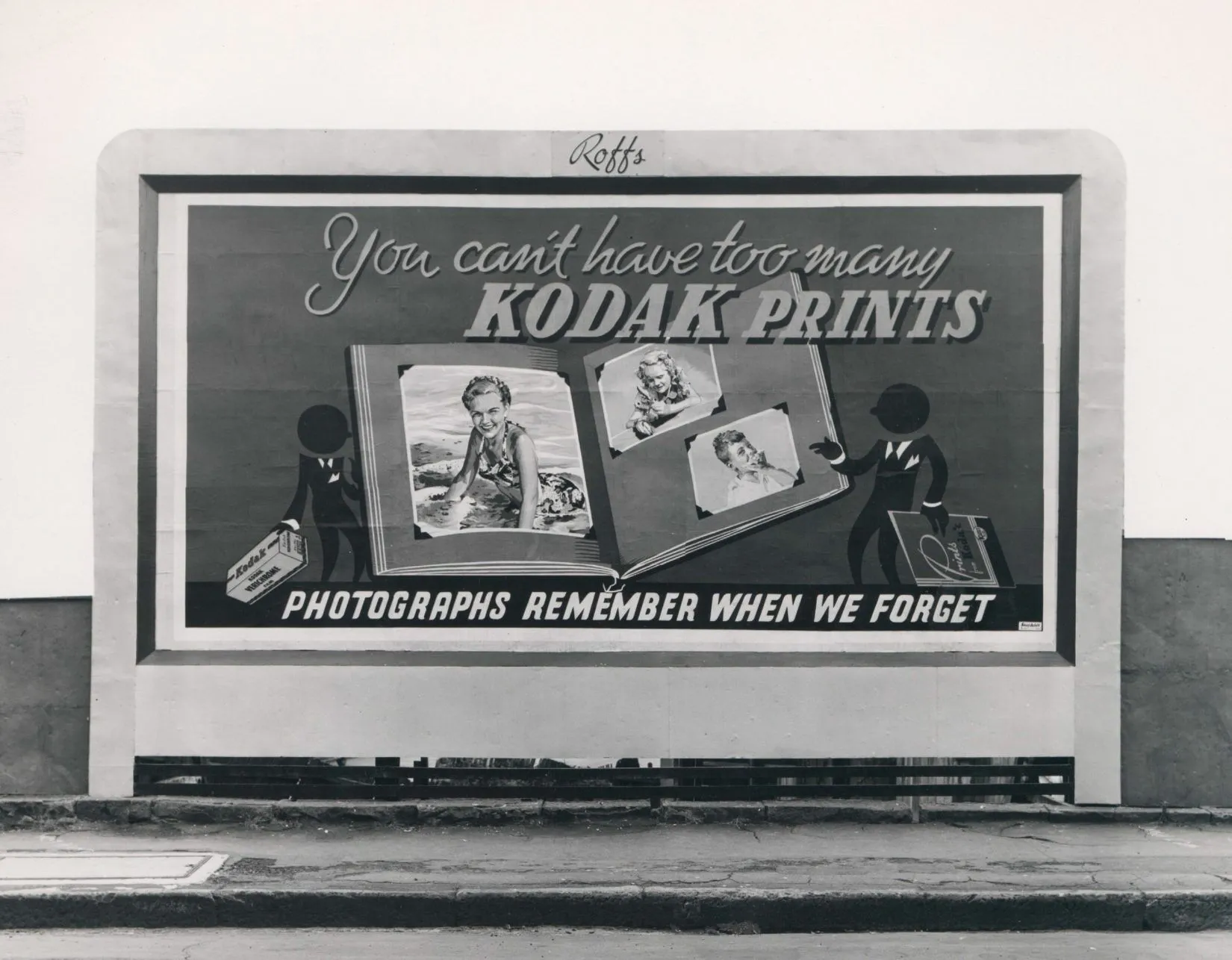

The George Eastman-led company got called out by some furniture and chocolate companies because their film wasn't working right. Light-grained or dark-grained wood tones in photographs developed from Kodak film all looked the same. Similarly, it took a lot of work to tell the difference between dark and milk chocolate. The advertising world bore the brunt of all controversies.

With their business on the line, Kodak decided to investigate.

Trivia: If you happen to find a picture from 50 years ago, there is a 90% chance it was clicked by a Kodak camera, captured on a Kodak film, and subsequently printed on a Kodak paper. — Business History

Technicolor, a revolutionary color motion picture process introduced in the early 20th century, transformed visual media by bringing vivid, saturated colors to the screen. Widely adopted in the 1950s, Technicolor replaced black-and-white photography, allowing audiences to experience films in full color for the first time. This technological leap soon extended to photography, making color photos accessible to the general public and enabling people to capture images that highlighted features like green eyes and fair skin in rich detail.

As the demand for photo processing and printing services surged, one-hour photo labs sprang up across the country to meet the need. Kodak, a key player in this industry, supplied many of these labs with printers. To ensure consistent color quality, each Kodak printer needed to be calibrated and standardized before printing. To achieve this, Kodak provided labs with a “Shirley Card,” a color reference card first created in the 1950s.

The Shirley Card featured a portrait of a woman named Shirley, along with six color patches, including primary colors (red, yellow, and cyan) and intermediate shades like pink, green, and another shade of blue. Shirley had light-colored eyes and fair skin, and her portrait was labeled "normal" beneath it. The goal, as explained by Harvard University art history and architecture professor Sarah Lewis, was to ensure that all Shirleys appeared well in every photograph. These calibration cards were also used in film and television, where Shirley was referred to as "China Girl," a nod to the porcelain mannequins used in early screen tests for makeup standards on set.

However, this standardization process primarily benefited lighter skin tones, as the Shirley Card was optimized for fair skin. As a result, people of color were often marginalized in the color processing, leading to less accurate representations in photographs.

In a New York Times article, Sarah Lewis, an art history and architecture professor at Harvard University, explains “When you sent off your film to get developed, lab technicians would use the image of a white woman with brown hair named Shirley as the measuring stick against which they calibrated the colors. Quality control meant ensuring that Shirley’s face looked good. It has translated into the color-balancing of digital technology. In the mid-1990s, Kodak created a multiracial Shirley Card with three women, one black, one white, and one Asian, and later included a Latina model, in an attempt intended to help camera operators calibrate skin tones. These were not adopted by everyone since they coincided with the rise of digital photography. The result was film emulsion technology that still carried over the social bias of earlier photographic conventions.”

Lorna Roth, a professor at Concordia University professor, says that it took complaints from furniture and chocolate manufacturers in the 1960s and 1970s for Kodak to start to fix color photography’s bias.

Earl Kage, Kodak’s former manager of research and head of Color Photo Studios, received complaints from chocolate companies who were dissatisfied with how their products' brown tones appeared in photographs. Furniture companies also raised concerns about the lack of color variation between different types of wood in their ads. According to the research by professor Roth, Kage had previously heard complaints from parents about the poor quality of graduation photos, where color contrast issues made it difficult to capture a diverse group accurately. However, it was the pressure from the chocolate and furniture companies that ultimately compelled Kodak to take action. Kodak may have gone bankrupt, often cited as a consequence of their lack of innovation and growing competition. And while movies like Black Panther, Moonlight, and Crazy Rich Asians showcase incredible representation, it might give the impression that the world has healed—but we still have a long way to go.

Earl Kage, Kodak’s former manager of research and head of Color Photo Studios, received complaints from chocolate companies who were dissatisfied with how their products' brown tones appeared in photographs. Furniture companies also raised concerns about the lack of color variation between different types of wood in their ads. According to the research by professor Roth, Kage had previously heard complaints from parents about the poor quality of graduation photos, where color contrast issues made it difficult to capture a diverse group accurately. However, it was the pressure from the chocolate and furniture companies that ultimately compelled Kodak to take action. Kodak may have gone bankrupt, often cited as a consequence of their lack of innovation and growing competition. And while movies like Black Panther, Moonlight, and Crazy Rich Asians showcase incredible representation, it might give the impression that the world has healed—but we still have a long way to go.

In 2024, despite having access to the best possible tools, many photographers, particularly white photographers, still struggle to capture darker skin tones accurately. These tools are as good as the people who use them. The challenge isn’t just technical but deeply cultural. We now have an abundance of technology that can faithfully represent any skin tone in all its richness and beauty but the stigma around darker skin remains deeply ingrained in many cultures. This conscious or subconscious bias often prevents photographers from doing justice to their subjects.

It is not enough to rely on equipment. Photographers must take the time to study how different skin tones interact with lighting and surroundings, to understand how to highlight and honor the authenticity of each individual. True progress lies in recognizing that photography is not just about capturing an image but about understanding the people being photographed.

“I suffered first as a child from discrimination, poverty ... So I think it was a natural follow from that that I should use my camera to speak for people who are unable to speak for themselves.”

Words to be remembered by Gordon Parks, American photographer, composer, poet and one of the most groundbreaking figures in 20th century photography.