Indians don’t just like butter. They glorify it. It’s not a condiment; it’s the finishing touch, the grand finale, the reason a dish goes from good to legendary. A simple parantha is fine, but a slather of butter makes it magic. Dal is comforting, but turn it into Dal Makhani—slow-cooked, buttery, rich—and it becomes something to write home about. Butter Chicken and Butter Garlic Naan, the undisputed royalty of North Indian cuisine, wouldn’t be the same without it.

But how did this love affair with butter begin, and why do we take it so far?

A hundred years ago, butter in India wasn’t the slick, branded staple we see today. It started as a humble byproduct—milk churned to collect malai (cream), a simple luxury savored at home. Then came the British, and with them, a new way of thinking about everyday commodities. Butter was no longer just food; it became a business, a brand, a product with a story to tell.

And for a long time, that story belonged to Polson.

The Birth of India’s First Butter Brand

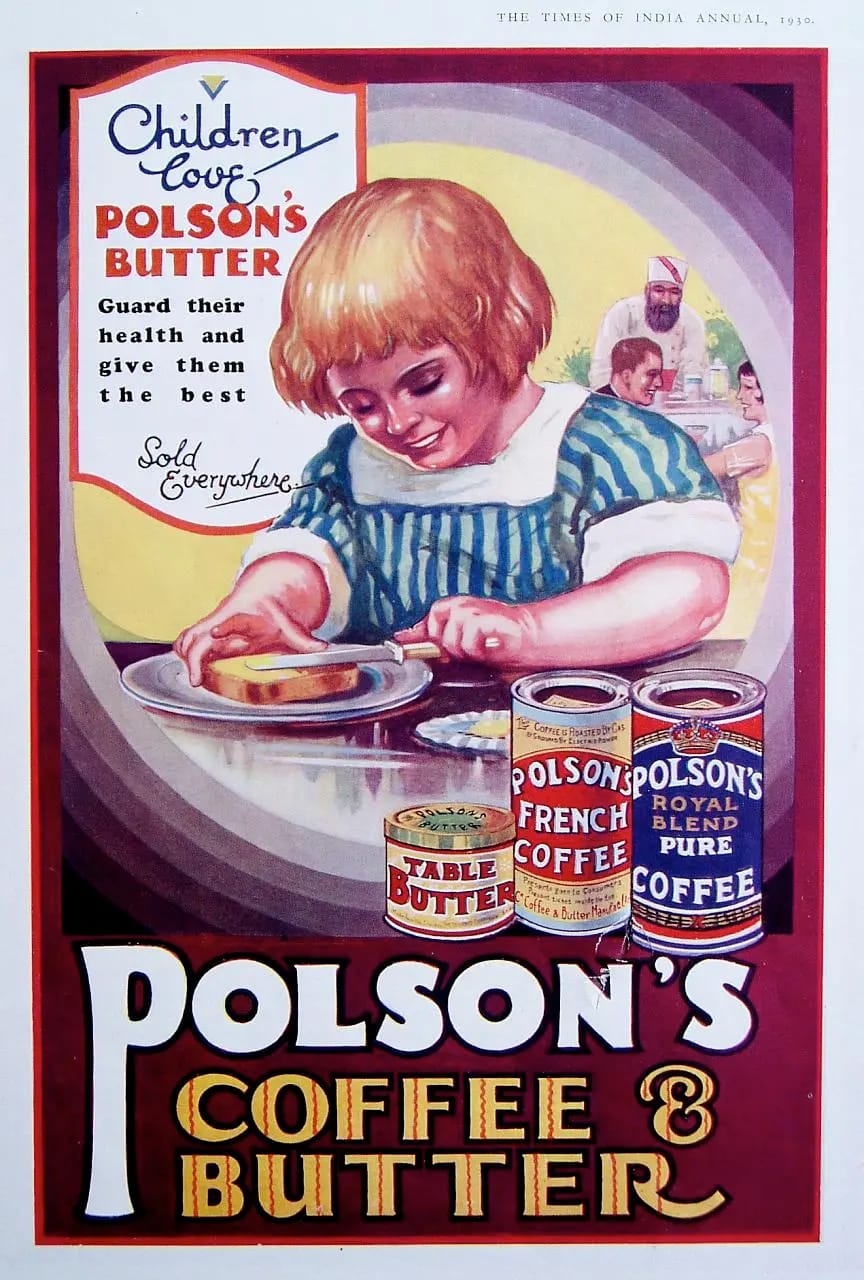

In 1888, a 13-year-old Bombay boy named Pestonji Edulji Dalal borrowed Rs 100 from his sister and rented a tiny shop for Rs 8 a month. He turned his nickname, "Polly," into Polson, a brand that felt British enough to impress colonial officers and elite Indians alike.

Polson was built on branding before branding was even a thing. When the British Army needed butter in 1910, Polson stepped in, setting up a dairy in Gujarat.

The butter itself was nothing extraordinary. But 110 years ago, it was marketed like it was.

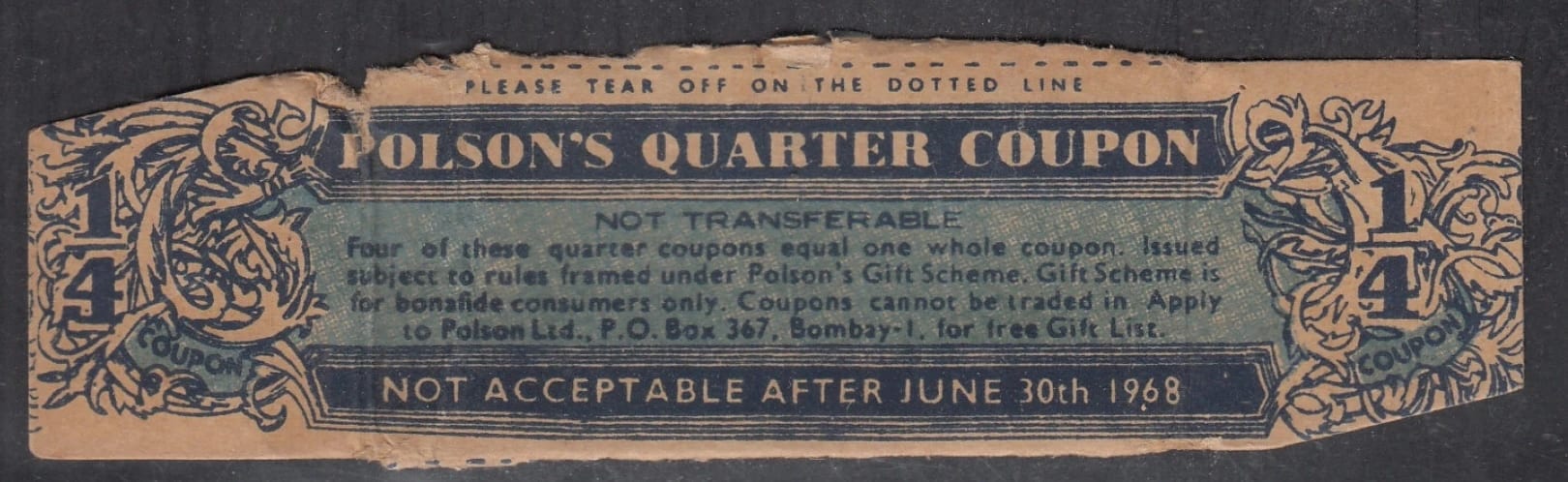

Polson butter came with coupons, redeemable for toasters and other fancy kitchen appliances. Owning it meant something. It was an early lesson in business: sometimes, the product isn’t the product—the status is.

For decades, it worked. Because for decades, people believed brands were built on exclusivity. But brands that last? They’re built on something else.

Polson ruled shop shelves, a symbol of aspiration in colonial India. But while it dominated the market, a quiet resistance was building—one that would rewrite India’s butter story.

The Beginnings: A Farmers' Struggle

By the 1940s, India’s dairy industry was monopolized. Farmers produced the milk. Middlemen took the profits. The Bombay Milk Scheme (BMS), launched in 1945 by the British government, sourced milk at dirt-cheap prices, while companies like Polson dictated rates.

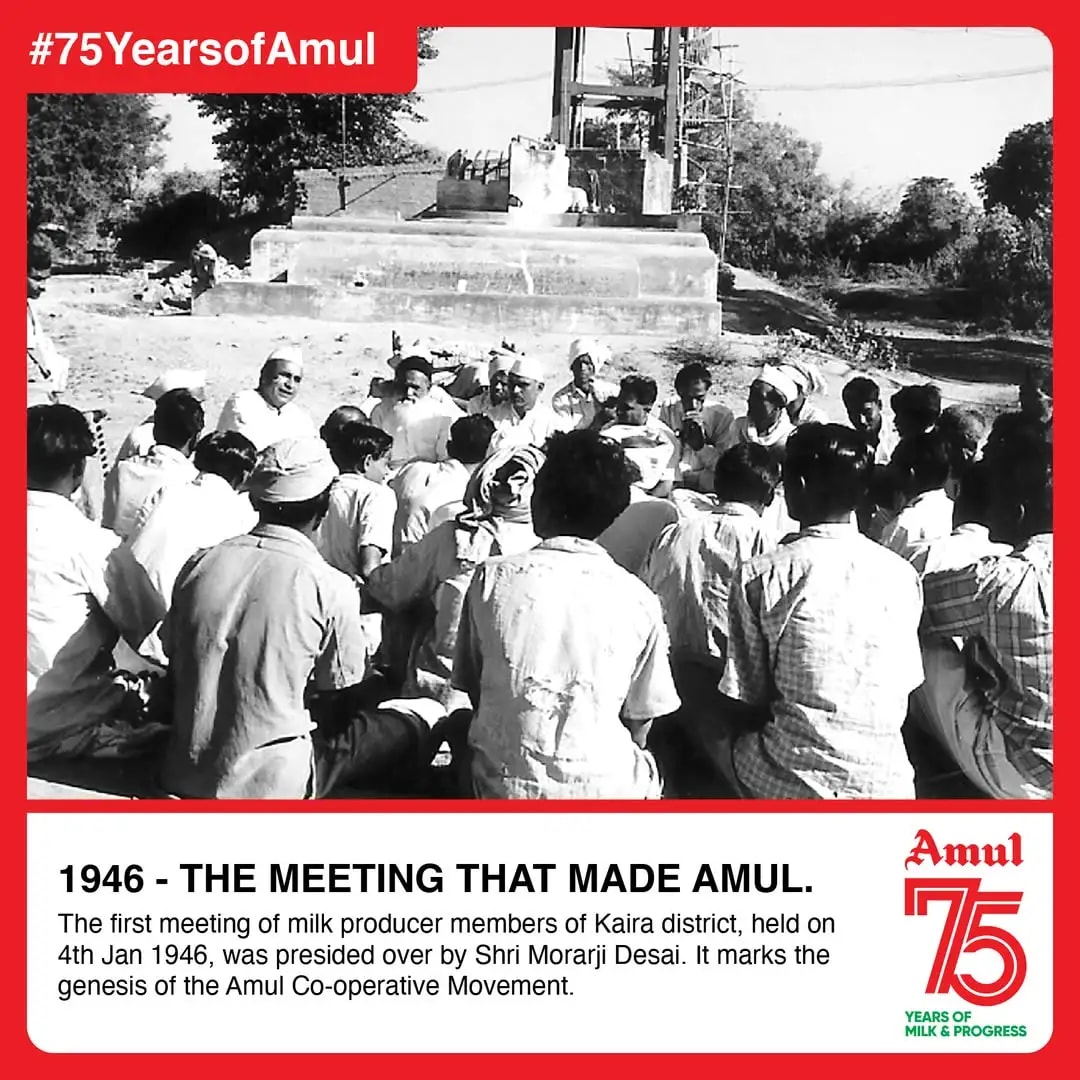

Farmers weren’t just frustrated. They were trapped. Then came Vallabhbhai Patel, freedom fighter and soon-to-be India’s first Home Minister, with a simple idea: take back control. If farmers worked together, they could bypass middlemen and sell directly.

On December 14, 1946, the Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers’ Union Limited (KDCMPUL) was born. A mouthful of a name, but an idea simple enough: milk farmers uniting to control their own supply chain.

Led by Tribhuvandas Patel, they walked from village to village, convincing farmers to join. Polson fought back. Farmers went on a 15-day strike, pouring milk onto the streets rather than selling it at exploitative rates. That moment marked the beginning of the end for Polson.

Because the best brands don’t just sell to people—they grow with them. And that’s why they win.

The Amul Revolution

By 1950, the cooperative needed more than just unity. It needed leadership. Enter Verghese Kurien, a dairy engineer with a metallurgy degree and zero interest of working in dairy.

Fate had other plans. A government scholarship had sent him to Michigan State University for dairy research. Upon returning, he was assigned to a dairy facility in Anand. He wanted to leave. Instead, he met Tribhuvandas Patel and witnessed what was happening.

Kurien stayed. Because this wasn’t just about milk—it was about power, independence, and changing the rules of the game.

He quickly realized that increasing milk production was only half the battle. Without a strong brand, they wouldn’t just be at the mercy of middlemen. They’d be invisible. And invisible brands don’t survive.

A chemist at the cooperative proposed the name Amul—derived from the Sanskrit word amulya, meaning priceless. It was more than just a name. It was a statement. A declaration that this was no ordinary dairy. This was something meant to last.

In 1957, the cooperative officially registered the Amul brand.

The Butter Battle

By 1952, the Kaira cooperative had increased its milk supply from 2,000 liters in 1948 to 20,000 liters. Farmers in Anand were now sending milk to Bombay in insulated railway vans.

As the cooperative’s success grew, so did its surplus milk. Kurien needed to find a way to use it. The obvious solution? Butter.

In 1955, the very first pack of Amul Butter rolled out of the factory.

It didn’t go well.

Consumers weren’t just used to Polson’s distinct taste—they were conditioned to crave it. Its cream was deliberately soured for days, then heavily salted to create a flavor that felt less like food and more like memory.

Amul wasn’t just fighting a brand. It was fighting nostalgia. And nostalgia doesn’t go down without a fight. They tweaked the recipe—more salt, a deeper yellow hue—small changes, but habits aren’t logic. They’re comfort. And Polson still dominated.

Kurien understood that great products aren’t enough. Success isn’t just about what you sell, it’s about what people remember.

And soon, a little girl in polka dots wouldn’t just sell butter. She’d sell a revolution.

The Advertising Genius of Amul

Polson’s branding was built on British aspiration. Its packaging featured a European-looking girl in a blue dress. That was its audience.

Amul had other plans.

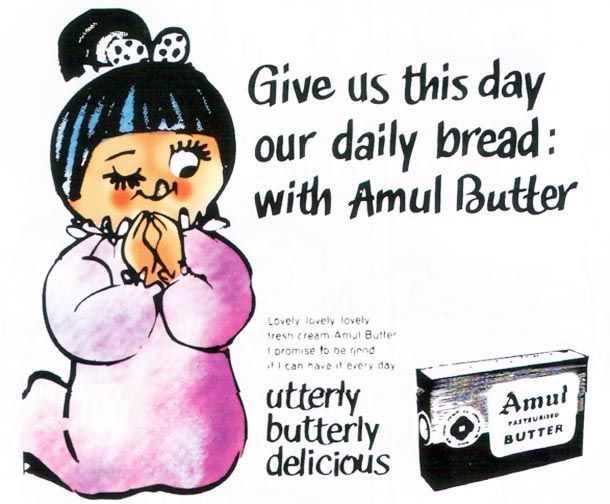

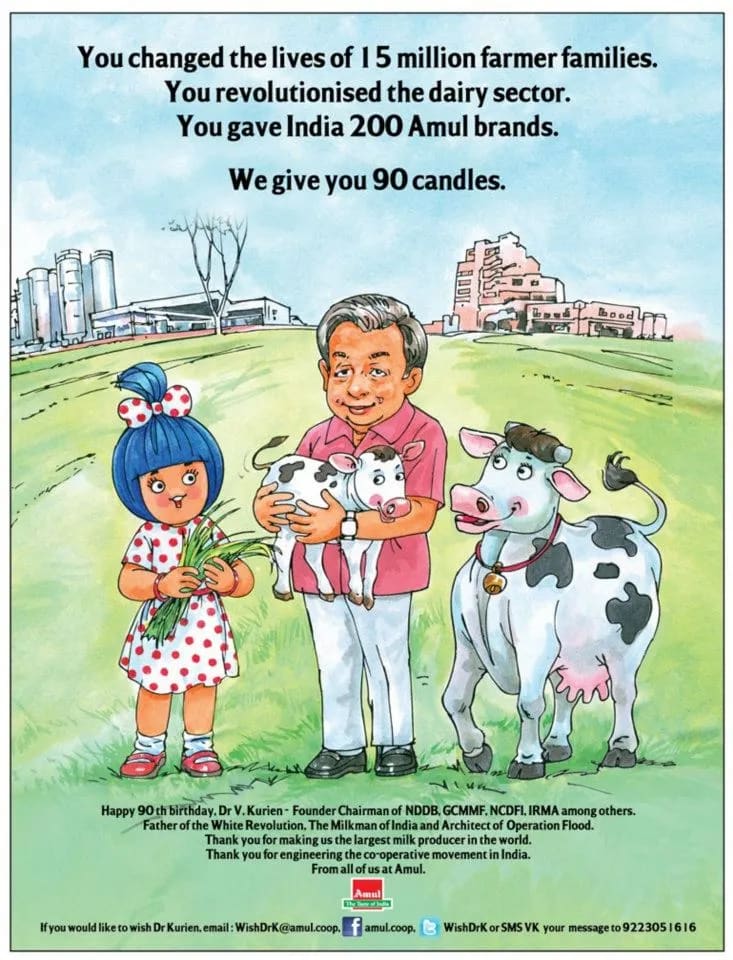

In 1966, they introduced the Amul Girl. A chubby, wide-eyed, mischievous girl who poked fun at politics, cricket, and pop culture. She wasn’t just a mascot—she was a voice. And people listened.

Created by art director Eustace Fernandes, the Amul Girl became the face of a brand that refused to take itself too seriously. And that was the genius of it. Relevance creates recall. Few brands understood this back then. Even fewer mastered it like Amul did.

The White Revolution: Ending Polson

By the 1970s, Amul wasn’t just beating Polson. It was taking over.

Kurien wasn’t content with that. He had bigger ambitions: he wanted India to stop importing milk altogether.

That vision turned into Operation Flood—the world’s largest dairy development program. It was modeled after Amul’s cooperative success. And it worked.

India became the world’s largest producer of milk, surpassing the U.S. by the late 1990s. Farmers who once struggled under middlemen now controlled their own supply chains. The White Revolution, as it came to be known, reshaped India’s rural economy.

Polson, once a market leader, disappeared. Not because it made bad butter. But because it failed to see what Amul saw: that nostalgia alone doesn’t build a legacy.

What Amul Taught the World

Most brands sell products. The great ones sell stories.

Amul did something even better: it built a movement. It took a basic commodity, turned it into a brand, and then turned that brand into a cultural institution.

Polson had the first-mover advantage. But first isn’t always best.

The brands that endure aren’t just the ones with good products. They’re the ones that adapt, stay relevant, and mean something beyond what they sell.

Today, the Amul Girl has outlasted governments, recessions, wars, and pandemics. She’s the longest-running ad campaign in history. Because relevance doesn’t expire.

That’s the lesson of Amul. A farmers' revolt, a stubborn dairy engineer, and a cheeky cartoon girl took down a giant.

Not because they made better butter. But because they told a better story.

And when it comes to brands, stories always win.